Stupidity and lies: the new standard for online debate?

Israel/Palestine. Russia/Ukraine. Brexit. Trump. The quality of online debate has arguably never been lower. Is it time for a reminder of the basics of rational thought?

“How fortunate for leaders that men do not think.” – Adolf Hitler

(I’ve got way too much for one post, so part one will deal with “stupidity”, part two with “lies”.)

Humans have been arguing for as long as they could speak. You’d think, given 200,000-odd years of practice – plus all the intervening research into rhetoric, logic and psychology – that we’d have it down to a fine art by now. And yet the vast majority of online debate these days seem to consist of little more than “You lost, suck it up”, “Moron”, “Liar”, and “Fuck you”. What happened?

Some social explanations have been put forward: the phenomenon of deindividuation – when we deal with anonymous avatars rather than real people, we don’t accord them the same respect – and the creation of ever more disparate echo chambers, or bubbles, of people who agree with us, leaving us less able to understand those who don’t.

Part of the problem, I think, is that most people aren’t remotely trained in critical thinking. Half the time, when people think or speak or write – and I include myself in this – they don’t know that they’re committing basic errors of reasoning. So I thought I’d put together a little list of some of the more common ones (and in my next post, some of the rhetorical cheats people use to exploit them), so that you can avoid tripping up when you’re debating – and politely point out when your opponent does.

I’m with stupid

Are Leave voters the dumb ones, or Remain? Do Clinton fans need educating, or do Trumpettes? Who’s the bigger fool: the liberal, or the alt-right fascist?

The uncomfortable fact is, we’re all idiots. Your brain, thanks to your evolutionary past, is prone to all sorts of errors and biases. The model of the world in your head is not an accurate representation of the world in front of you.

Sure, humans can be amazing. We’ve been to the moon, we’ve cured smallpox, we’ve figured out the structure of DNA and made computers that fit on a fingernail. But we also text while driving. We hook up with our exes, we pump industrial waste into lakes, and we laugh at Mrs Brown’s Boys. Even Einstein mislaid his keys.

This is because there’s a lot of information coming at us, 24/7. And our brains, while capacious, can’t take it all in – they need to winnow, to precis, to prioritise, often instantaneously. And while we generally think of ourselves as rational beings, all too often, our thought processes are derailed by inbuilt prejudices; emotion, wording, status, looks.

Full disclosure: I’m not the world’s leading authority on this subject. I’ve picked up most of this from reading books and websites (although after 25 years of subediting, I’d like to think my critical thinking skills aren’t a complete disgrace). What’s more, there’s still a lot of disagreement even among the experts about terminology and classification, not least because these areas straddle the separate domains of psychology and logic, and as a result, some of my definitions may be a little fuzzy. But the basic principles are solid enough, and should be of some use to anyone looking to improve the standard of their online discourse.

For a more in-depth, comprehensive and authoritative list of cognitive biases, you could do worse than check out this site.

And please try not to be put off by the big Latin words. I didn’t coin them!

Dunning-Kruger effect

AKA illusory superiority.

Time and time again, studies have shown that most people consider themselves more intelligent than average. Most people also consider themselves better drivers than average, better-looking than average, and nicer than average. Which can’t, obviously, be the case, because statistically speaking, only half of us can make that claim.

Why is this so? Because human self-esteem is a fragile thing. In order to drag ourselves through the daily grind, we have to convince ourselves that we’re in with a shot of happiness, of success, that we can hold our own. Consequently, we think of ourselves as being at least competent at everything. (Those who suffer from depression, though, often report feeling the opposite.)

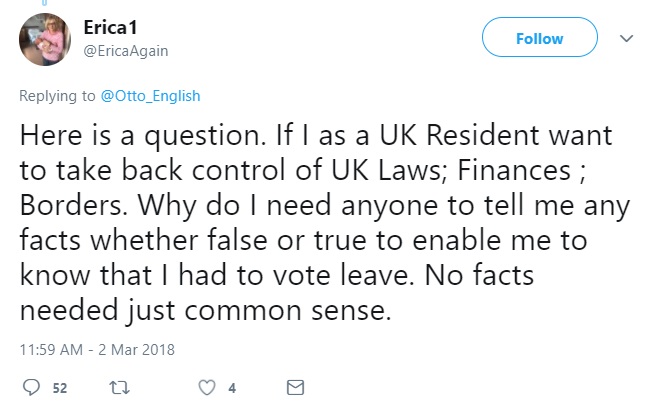

But there’s a more alarming twist. When you start learning a discipline, you quickly come to realise exactly how much there is that you do not know. Someone who has never studied that discipline, on the other hand, does not have that insight. Instead they tend to assume that their passing acquaintance with the subject, combined with their natural, above-average intellect, qualifies them to have an opinion. In short, amateurs are often more likely to believe that their opinions on a subject are valid than experts are.

“People have had enough of experts.” – Michael Gove

Third-person effect

You believe your opinions are based on experience and evidence and fact, and that people with opposing views are gullible and susceptible to propaganda. In reality, you are probably just as susceptible as they are.

Confirmation bias

Related to: cognitive dissonance

Again, it’s all about self-esteem. People like to build up an image of ourselves – an identity – that is strong and above all consistent. As a result, we tend to seek out information and people and things that support our existing beliefs, rather than sources that contradict or threaten it. This is why Arsenal supporters rarely subscribe to MUTV, and why ardent admirers of Taylor Swift are more likely to follow other Swifties on Twitter than Katy Perry fans.

If we do this for long enough, we create echo chambers around ourselves, filled with people and things that reinforce our world-view. So when we are eventually confronted with evidence or opinions that threaten it, we react with intolerance, or even hostility.

“Hello, I’m a rabid xenophobe. Do you have any copies of the Daily Express?”

“There’s nothing you can say that will interest me, you fucking libtard.” [liberal retard]

Backfire effect

The tendency to harden your stance when you come up against evidence that contradicts your position. Widely observed among Remain and Leave voters since the referendum – rather than seeking compromise or to better understand opposing views, many people have “doubled down” and entrenched their positions.

Self-serving bias

On a similar note, most people, when something good happens, tend to believe that it’s a quality within themselves, or within their “ingroup” (people they share an identity with), that was responsible. Any failures, meanwhile, will generally be blamed on outside forces. So if you pass an exam, you’ll probably come away thinking, “Wow, I deserve that because I worked really hard for it”, but if you fail, you might think, “Stupid teacher totally failed to prepare me for that.”

“Wow, Team GB did so well at the Olympics. Isn’t Britain amazing?”

“The NHS is falling apart, and it’s all the fault of those bloody immigrants.”

Choice supportive bias

AKA defensiveness, special pleading.

Sometimes, when you have to make a decision, it’s a bit of a coin-toss. You genuinely don’t know if you will have a better time at the local club or at the bowling alley. So you choose the bowling alley … and it turns out to be a disaster. Brian breaks his wrist and Trish loses her phone. But when someone has the temerity to criticise your choice, you leap to its defence, citing all sorts of reasons in favour of the decision – reasons that you didn’t even think of when you made it. This bias, which again boils down to self-esteem, tends to be more pronounced in older people.

“I voted Leave because I thought the Remain campaign’s predictions of economic problems were just fearmongering.”

“But sterling has tanked and investment is down and food prices are rising.”

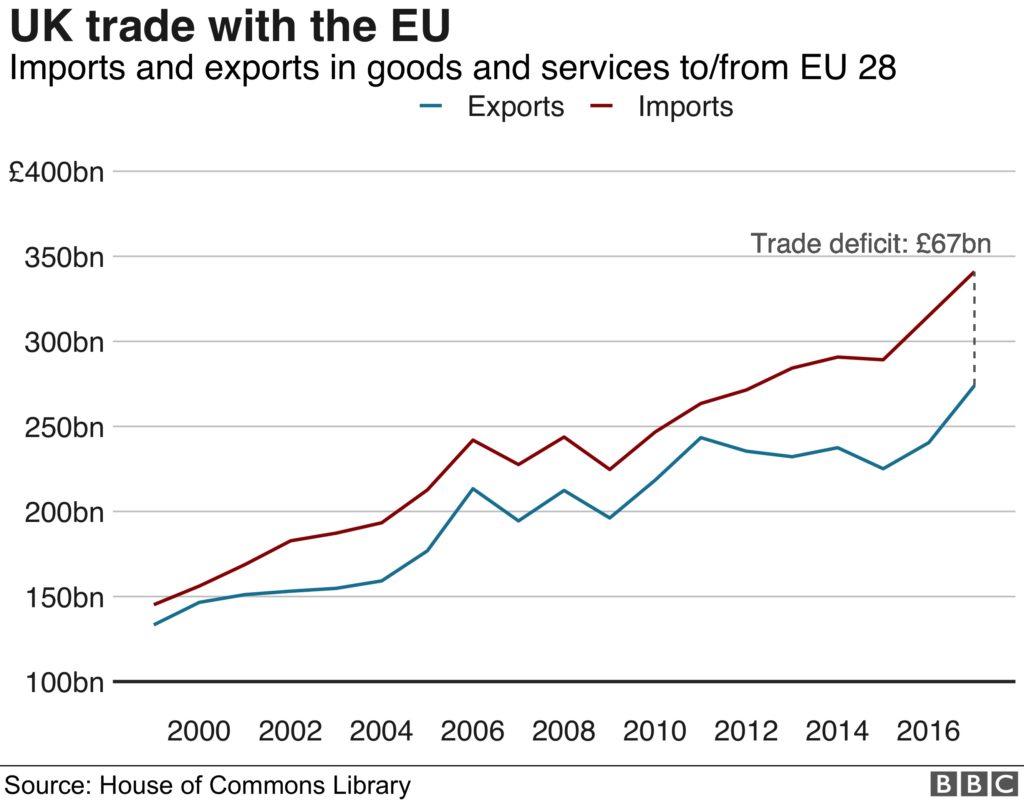

“Everyone knows that sterling was hugely overvalued, and anyway, it’ll be great for our exports!”

Cult indoctrination

When you read about cults in the papers, you probably think, “How could any of these people be so weak-minded as to fall for that crap?” But the unfortunate reality is that most people, given impoverished circumstances, some catchy slogans, a big enough crowd and a sufficiently charismatic figurehead, are more than capable of being coopted into a religious or quasi-religious sect. Our innate desire to belong to a group is very strong, rooted in millions of years of tribal culture, as is our propensity to kowtow to authority figures. This often leads us to overlook flaws in authority figures, to fail to question them, and to follow their bidding without question.

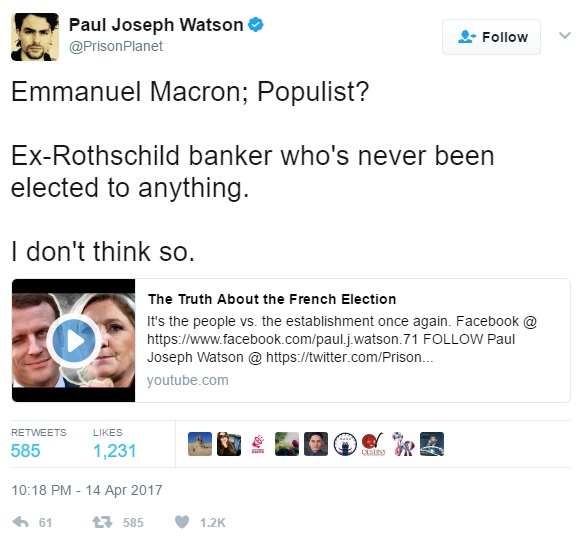

“Oh my God, like – like – Gee, I can’t – Paul, Paul Joseph Watson, you are like, like – everything to me, I just …”

“Lock her up! Lock her up! Lock her up!”

Projection illusion

AKA false consensus bias.

While everyone likes to think they’re a bit special, few of us want to be seen as a freak. On the whole, people crave acceptance; we want to fit in, to be liked and understood. So we seem to have an inbuilt predilection for believing that everyone else – at least, everyone else in our little cabal – thinks the way we do. In the absence of any clear signals, we project our own wishes, desires, interests, concerns, ethics and moral code on to others.

If you’ve never taken sugar in your tea, you’ll probably raise an eyebrow when you meet someone who asks for two. And if you’ve grown up in an omnivorous household, your first invitation to a vegetarian dinner party is likely to come as a shock.

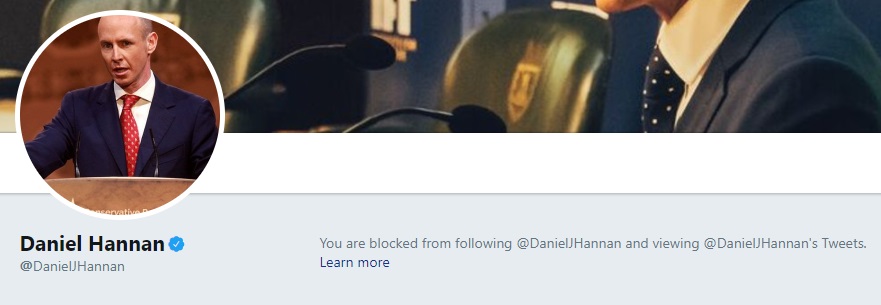

“You have no idea why most people who voted to leave did so. Most people voted over the immigration issue” – garyhumble, Guardian website

“Immigration was not the top issue for Leave voters, however much Remainers *want* it to have been” – Daniel Hannan MEP (tweet, now deleted, but still in Google cache)

Nostalgia fallacy

Nostalgia fallacy

AKA Pollyanna principle, golden age fallacy, positivity bias.

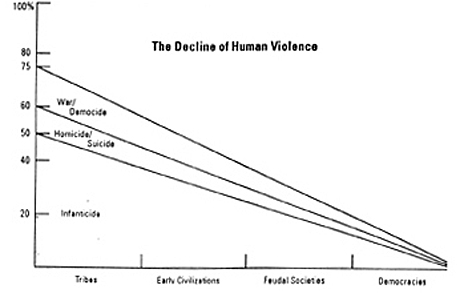

“Thiiiiings … ain’t what they uuuused to be …” It’s been the lament of every older generation since the dawn of time. And yet history shows that broadly speaking, the quality of life has consistently improved for most people the world over. The standard of living in western countries, at least, has followed an almost uninterrupted curve upwards for 2,000 years; life expectancy has improved, rates of crime have fallen, wars and disease and famine have become less common, and technology has made our lives easier. Whence this disparity?

It turns out, it’s because when recalling past events, people have an innate tendency to remember positive experiences and suppress the negative ones. You’ll often hear older people waxing lyrical about the sense of community and the trees and fields and the games of cribbage round the fireplace, while conveniently glossing over the freezing outdoor toilet and the regular beatings from Dad and the cousin who died of polio.

“I know from the days before the common market that we did OK, we did fantastic, and we can go back to that” – May Robson, Sunderland resident

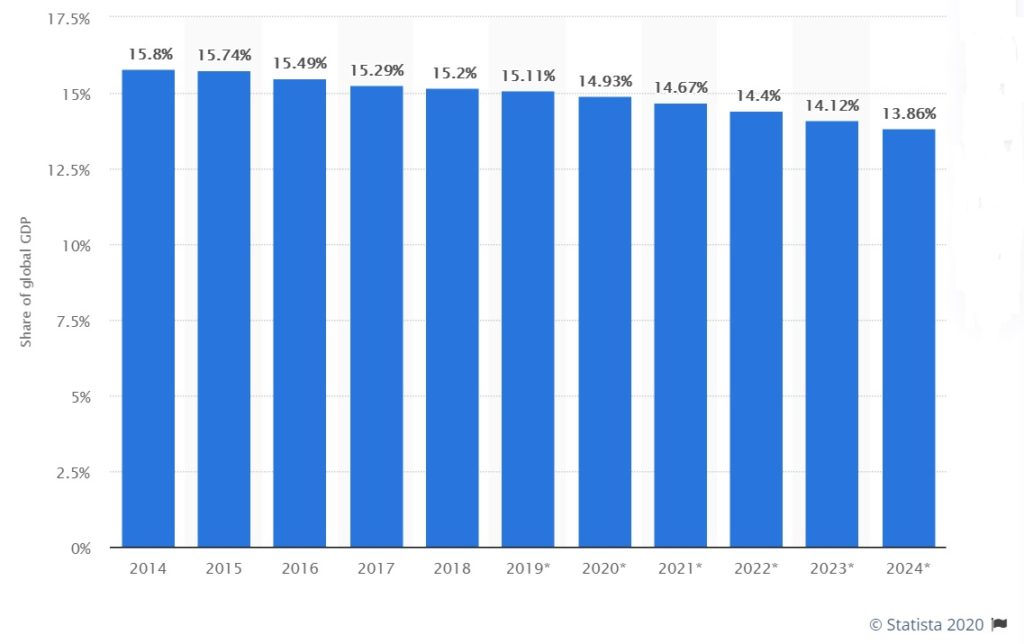

[In the early 1970s, prior to signing up to the EEC, the UK was known as the “Sick Man of Europe”. Its beaches and skies were polluted, wages were depressed, inflation was high, and industry was in decline. During the first 42 years of its membership of the EU, UK GDP grew by almost 250%, outperforming most major world economies.]

Threat hypersensitivity

We’re all going to die. We try not to dwell on it too much, but our fear of mortality informs our every moment. We go to great lengths, consciously or otherwise, to avoid things that might endanger our lives. Some people find religion useful in submerging this fear; some throw their energies into raising a family; others base their hopes for pseudo-immortality on historical fame, or works of art or engineering.

It turns out that even mentions of death can markedly affect our behaviour. When people are reminded of their mortality (say, by a news story about a terrorist attack), they tend to defend their world-view, and people who share that world-view, more strongly. According to terror management theory, reminding people of their mortality tends to shift people’s politics to the right.

“We have a situation where we have our inner cities, African-Americans, Hispanics are living in hell because it’s so dangerous. You walk down the street, you get shot.” – Donald Trump

“It’s a total disaster, on top of which you have migration which is destroying Europe,” he said at an event in September. “Germany is a disaster now. France is a disaster.” – Donald Trump

“Fix our broken mental health system. All of the tragic mass murders that occurred in the past several years have something in common – there were red flags that were ignored.” – Donald Trump’s campaign website

Correlation v causation

This encapsulates a range of logical snafus, but I’ll confine myself to a couple of examples.

Humans have a habit of drawing conclusions from limited information. Say a football player happens to wear red underpants for a particular match, and his team wins handsomely. Then, in the next match, when he wears his blue strides, they lose. He might conclude, since victory coincided with red-pant-wearing and defeat with blue, that the red pants are responsible, and thus decide to wear the red pants for every match. He’d be a fucking bellend if he did, but this is a mistake people make all the time.

For a more complex example, consider the deadly Mr Whippy. It’s a proven fact that every time ice-cream sales rise in an area, the local murder rate rises too. Could this really mean that Magnums turn people into killers? Well, no, it’s more likely the fact that in warmer weather, people buy more ice-creams – and they also stay out later, drink more, and interact more with other people.

“This country’s been going to the dogs ever since we joined the EU. It’s high time we got out.”

Availability heuristic

AKA attention bias, anchoring bias; closely linked to the above.

If you see (or hear about) a particular event, you are more likely to think it is far more prevalent than is actually the case. The classic example of this is fear of flying: many people refuse to get in an aircraft because they are worried that it might crash, but in fact, each time you take off, your chances of carking it are only about 1 in 10 million. The reason we think air disasters are more common than they are is that when they do happen they are, understandably, given extensive coverage.

“I voted Leave because our prisons are full of Polish rapists.”

[As of March 2016, there were 965 Polish nationals in British prisons. That’s out of a total Polish population of just over 800,000 — so 0.12% of all Poles here are convicted criminals. The total number of prisoners is around 95,000; about 0.14% of the population as a whole. I can’t find any figures broken down into both ethnicity and crime. So unless Polish rapists are better at avoiding detection than British ones, or the CPS for some reason is softer on eastern European sex offenders, they’re no worse than the natives.]

Generalisation

Possibly the most insidious – and thus the most invidious – of all cognitive errors, generalisation covers a wide range of sins, including the out-group homogeneity effect, illusory correlation, attribution errors, essentialism, the representativeness fallacy and stereotyping. But they all essentially boil down to the same thing: the human mind abhors an information vacuum.

Picture yourself as the alpha male of a savannah-dwelling tribe of hominids around a million years ago. (Ooh, primal!) You’re stalking through a wooded glade with a companion when you spot a spider on his neck. He cries out and brushes the spider off. A few hours later, he’s dead. To avoid a repetition of the tragedy, you forbid the tribe from foraging anywhere where they see a spider. Sadly, this means you can no longer access any of your food sources, so you all starve and die. D’oh!

The fact is, less than 30 of the 43,000 or so species of spider (less than 0.1%) have ever caused a human death. Avoiding every spider is an irrational and costly response to the (exceptionally rare) problem of spider bites. What you’ve done here, Ogg, is generalise, or stereotype, in a most unhelpful way. You’ve (correctly) identified a link between a spider and a death, but you’ve extrapolated the qualities of one spider to all spiders, and consequently stone-tooled yourself in the foot.

Historically, this ability to derive sweeping rules from limited information would often have been useful. Water from little lake bad. Put leaf on wound good. But in the modern world, where life-or-death situations are far less frequent and it’s become almost impossible to judge a book by its cover, the knee-jerk response is rarely the right one.

“Typical Remoaner.”

“You liberals are all the same – patronising, smug and condescending.”

Default Bias

AKA status quo bias.

Many people (Remain voters, I’m looking at you. I mean us) naturally favour a situation simply because it pertains right now; because it works, more or less, and because they fear that any significant change might jeopardise that. I’d argue that it’s a fairly justified fear when no one actually has any credible idea of what to replace the status quo with.

“If it ain’t broke …”

Nihilism

AKA “Tear it all down!”

Polar opposite of the above fallacy. A blind rejection of what exists in favour of what could be, no matter what the likely cost. A disorder particularly common among infants and psychopaths.

The sunk cost fallacy

AKA argument from inertia.

One of the more personally costly mistakes people make.

You realise, at the end of a trying first year of your university course, that you don’t like your subject. What do you do? If you switch courses, you’ve basically wasted a year of your life. But if you stick it out, you might have wasted three.

We often think, once we have set out on a certain path, that the best course of action is to see it through no matter what. “I can’t back down now,” we say. “I mustn’t lose face.” To give up now would mean admitting that we were wrong, which is harmful to our self-esteem.

Logically speaking, it’s much better to have been a bit wrong in the past than to be massively wrong in the future. It usually makes sense to quit sooner rather than later, and give yourself more time to make a success of your next plan. But no, we still watch crappy movies all the way to the end, we still stay in doomed relationships for far too long, and we persist in pursuing disastrous policies.

“Get used to it. We’re leaving.”

Coming soon: logical fallacies and dangerous, lying bastards.

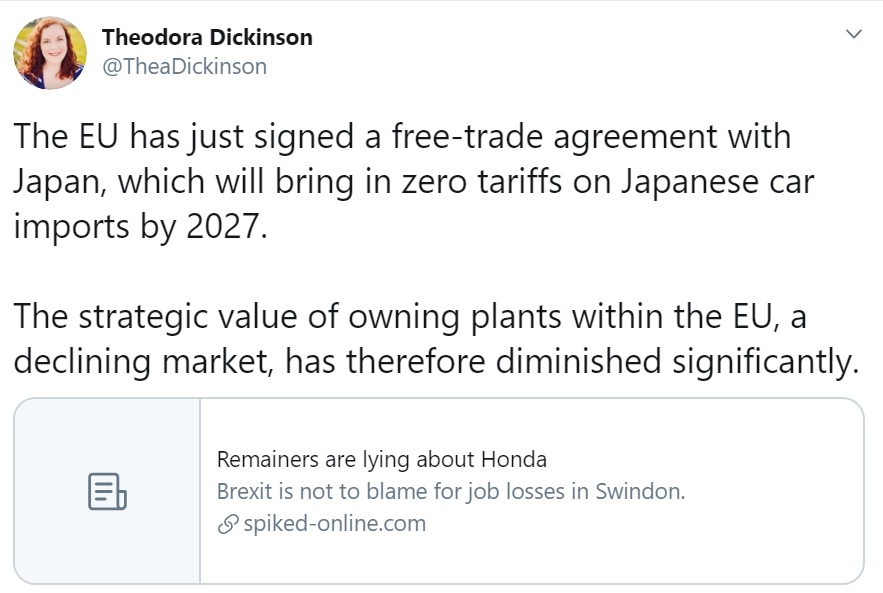

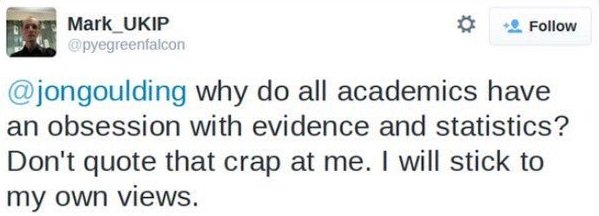

They’re assisted in this by the dumbed-down clickbait culture that’s consuming our media. The coverage of science in most newspapers these days is woeful: research findings are published without caveat, rebuttals added too late, if at all. And on news programmes, it’s increasingly rare to see a genuine expert consulted on any issue of note. You can understand why: academics can be a little dry and stuffy, their arguments detailed, nuanced, full of ifs and buts.

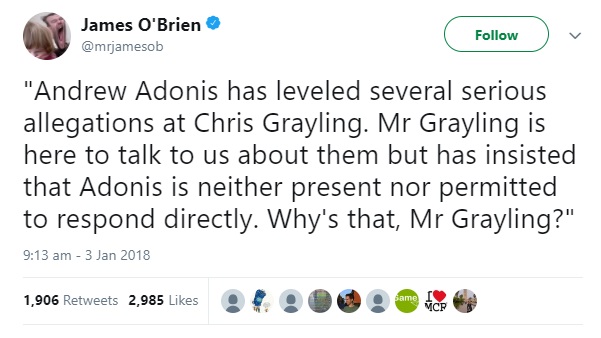

They’re assisted in this by the dumbed-down clickbait culture that’s consuming our media. The coverage of science in most newspapers these days is woeful: research findings are published without caveat, rebuttals added too late, if at all. And on news programmes, it’s increasingly rare to see a genuine expert consulted on any issue of note. You can understand why: academics can be a little dry and stuffy, their arguments detailed, nuanced, full of ifs and buts. If a showdown with someone who knows their stuff is unavoidable, far right-demagogues have several ploys. The crassest is simply to prevent their opponent from getting a word in edgeways, as

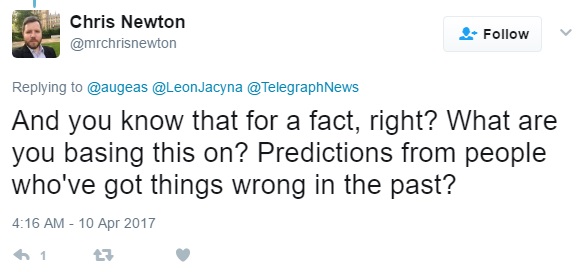

If a showdown with someone who knows their stuff is unavoidable, far right-demagogues have several ploys. The crassest is simply to prevent their opponent from getting a word in edgeways, as  Yes, they goofed up once. (Or rather, a different group of economists did; that was 10 years ago.) But those economists were appointed to their jobs over thousands of hugely qualified rivals. If they weren’t generally good at their jobs, they’d have lost them long ago. They’re still far more likely to make accurate forecasts about the UK’s future outside the EU than Kev from Castle Point.

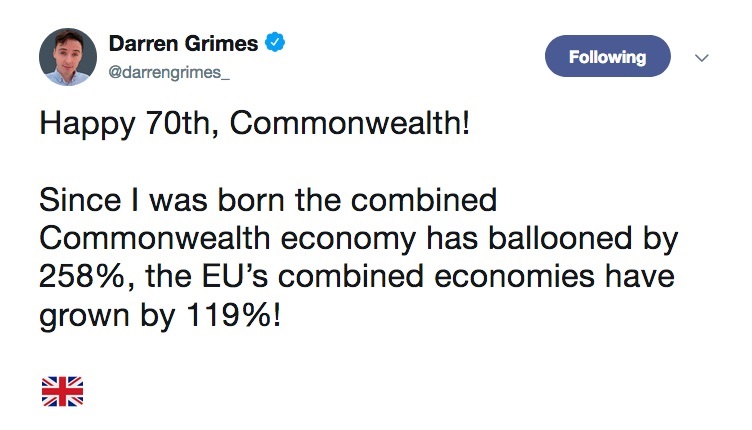

Yes, they goofed up once. (Or rather, a different group of economists did; that was 10 years ago.) But those economists were appointed to their jobs over thousands of hugely qualified rivals. If they weren’t generally good at their jobs, they’d have lost them long ago. They’re still far more likely to make accurate forecasts about the UK’s future outside the EU than Kev from Castle Point.

If any of these deluded souls had ever been within a country mile of a campus, they’d know the truth was more mundane. With the exception of the politics faculty and the student union offices, universities are not especially political places. Some right-on loon might make the news every few weeks with a call to ban music from campus because it’s discriminatory against deaf people, but most courses don’t even touch on politics (students of history and the social sciences make up 8% of the corpus) and membership of political groups is low. Most students aged 18-21, like most non-students aged 18-21, are more interested in beer, sport and sex than they are in social welfare budgets or the privatisation of the Land Registry.

If any of these deluded souls had ever been within a country mile of a campus, they’d know the truth was more mundane. With the exception of the politics faculty and the student union offices, universities are not especially political places. Some right-on loon might make the news every few weeks with a call to ban music from campus because it’s discriminatory against deaf people, but most courses don’t even touch on politics (students of history and the social sciences make up 8% of the corpus) and membership of political groups is low. Most students aged 18-21, like most non-students aged 18-21, are more interested in beer, sport and sex than they are in social welfare budgets or the privatisation of the Land Registry. We’re fully into wackjob territory now. I know George Soros is rich, but to fund every Remain vote and leaflet and march and pro-Remain MP and academic and research paper and CEO and judge and economist, and keep it all a secret … You know what? If that did turn out to be the case, I’d remain a Remainer, because I’d want to be on that man’s side.

We’re fully into wackjob territory now. I know George Soros is rich, but to fund every Remain vote and leaflet and march and pro-Remain MP and academic and research paper and CEO and judge and economist, and keep it all a secret … You know what? If that did turn out to be the case, I’d remain a Remainer, because I’d want to be on that man’s side.

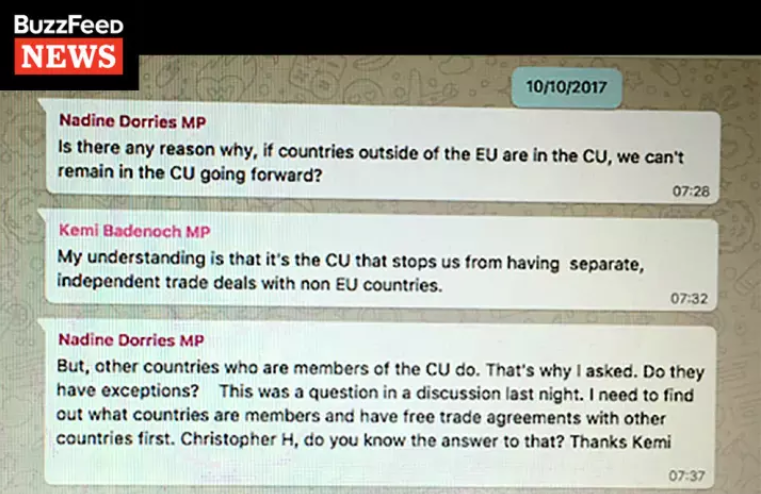

Nadine Dorries (MP!) came in for a lot of stick for her assertion that the vote to leave the EU was correct

Nadine Dorries (MP!) came in for a lot of stick for her assertion that the vote to leave the EU was correct

Their passion is not wholly misplaced. As we’ve seen, the system 1 brain, honed over millennia, is a perfectly good remedy to many problems. You sure as hell don’t want to be hanging around engaging your Spock when there’s a rock hurtling straight at your head.

Their passion is not wholly misplaced. As we’ve seen, the system 1 brain, honed over millennia, is a perfectly good remedy to many problems. You sure as hell don’t want to be hanging around engaging your Spock when there’s a rock hurtling straight at your head.

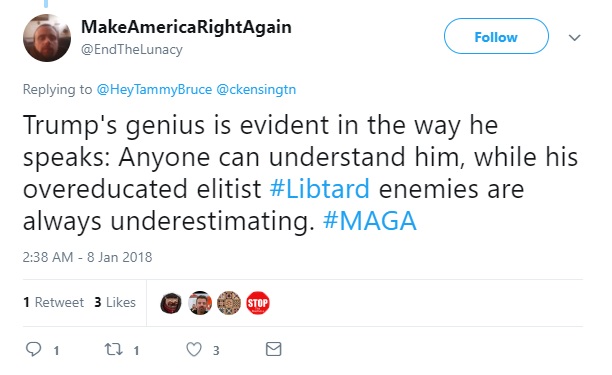

This, my populist friends, is the end result of the process I’ve been banging tiresomely on about. This is

This, my populist friends, is the end result of the process I’ve been banging tiresomely on about. This is