• Part 2: ‘We send the EU £350m a week’ (no, we don’t)

• Part 3: Why are all polling companies run by Tories?

• Part 4: ‘The UK is the fastest-growing economy in the G7’ (no, it isn’t)

Maths is scary.

There are plenty of maths wizzes out there, of course, and most of us, when the necessity arises, can perform basic calculations. It’s just that these operations don’t come naturally to human beings. For most of our species’ history, there was little need for any more mental arithmetic than “one/two/many” and “our tribe small, their tribe big”.

If your brain isn’t adequately trained, maths requires serious mental effort, which most of us will go to any lengths to avoid. As a result, when confronted with a differential equation or trigonometry problem, we curl into a ball and whimper, “Oh, I’m rubbish with numbers!”

So when it comes to statistics, just as with molecular biology and nuclear physics and translating ancient Phoenician, we tend to leave things to the experts. The catch is, the main conduits of this knowledge from professors to public – the media – are as clueless about maths as we are.

As a veteran of journalism of 25 years, I can let you in on a scary secret: reporters – even reporters who are specifically charged with writing about business and science and trade – rarely have any sort of background in maths or economics. Most of those who aren’t media studies or journalism graduates studied humanities (English, modern languages, history, politics, law), and the same goes for the subeditors and desk editors whose job it is to check their work. In the average newspaper office, you can count on the fingers of one hand the number of people who tell an x-axis from a y-axis, a percentage point from a percentage or a median from a mean. And TV interviewers, judging by their performance before and since Brexit, are no better.

Most of us aren’t too bad at figuring out when people are trying to mislead us with words or facts or pictures. But because we’re useless with numbers – and the gatekeepers are too – we’re much more susceptible to numerical shenanigans. Statistics can be massaged, manipulated, misrepresented and murdered as easily as words can. And it is this human weakness that the populists are counting on.

What I want to try to do in the next few posts is look at some of the more common examples of statistical chicanery that you will come across, in the hope that at least a few more people can start calling out the bastards who are trying to rip our society apart. (If I miss any obvious ones, please add your suggestions in the comments.)

(If you have no time to read on, I beg you to consider buying or borrowing a copy of Anthony Reuben’s Statistical: Ten Easy Ways To Avoid Being Misled By Numbers (Constable, 2019). It’s clear and concise and bang up to date, covering Brexit and Trump (but not coronavirus), and an easy read even for the fraidiest maths-phobe.)

The truth, the half-truth, and nothing like the truth

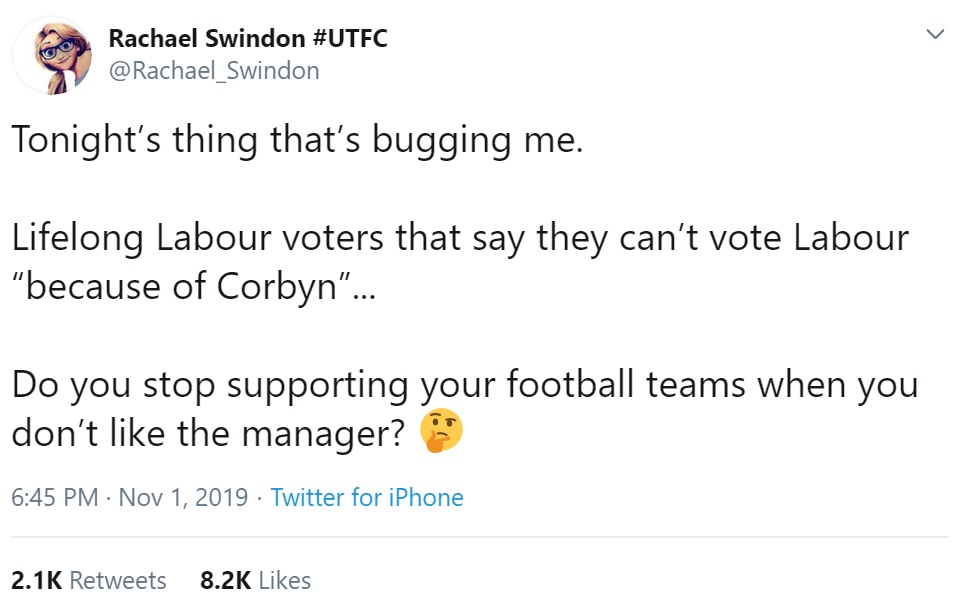

Sometimes, of course, as our present government demonstrates on a daily basis, populists are perfectly happy to forsake real numbers for entirely imaginary ones.

Think Owen Paterson’s assertion that only 5% of Northern Ireland’s trade is with Ireland, when the true figure is at least 30%; Jacob Rees-Mogg merrily retweeting the Sun’s innumerate bollocks about how much cheaper your shopping basket will be after Brexit; Dominic Raab overstating the cost of the CAP to British agriculture by a factor of 1,600%; Daniel Kawczynski’s ludicrous lemons claim; Matt Hancock counting pairs of gloves as two individual items of PPE; Matt Hancock including coronavirus tests on the same person and testing kits put in the post in the 100,000 total of tests carried out; Matt Hancock counting nurses who haven’t left towards the total of extra nurses employed; Boris Johnson, and thus, subsequently, the entire Conservative party, repeating until blue in the face that the Tories are building 40 new hospitals, when in fact they have committed to only six; Boris Johnson’s claim in January 2020 that the economy had grown by 73% under the present Tory government, when in fact the data covers the period back to 1990, which includes 13 years of Labour; Boris Johnson’s brazen and still unretracted claim that there are 400,000 fewer families in poverty since the Tories came to power, when in truth there are 600,000 more.

The chief drawback of straight-up untruths, of course, is that they’re easy to check and challenge. Most of the fictions above were exposed as such fairly quickly (though not before they’d burrowed their way into a few million poorly guarded minds). A far more effective way of misleading people is to present numerical information that is not incorrect, per se, but which tells only part of the story. To offer up, if you like, a fractional truth.

11/10 for presentation

If you’ve ever used a dating app, chances are you didn’t upload as your profile picture that zitty red-eye selfie you took in the Primark fitting room. You hunted through old snaps, maybe asked a camera-handy friend over for a mini-shoot, possibly even added a flattering filter, did a bit of Photoshopping, and judiciously cropped out the boyfriend. In short, you went to reasonable (or extreme) lengths to paint yourself in the best possible light.

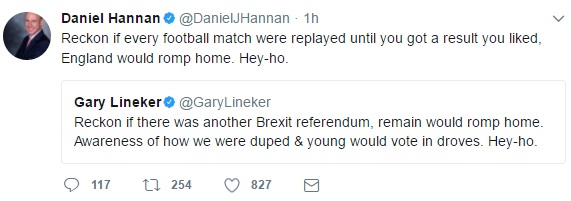

This process – statisticians call it “cherry-picking”, but I prefer “Instagramming” – is the populists’ most common way of abusing numbers (it can also be applied in reverse, to show something in its worst possible light). If the absolute figure (say, 17.4 million) is the most impressive, use that. If the percentage best advances your case, use that (but if it’s, say, only 51.9%, poof! It’s gone). If neither of those works to your advantage, what about the trend?

Which brings us to our first example.

‘Trade with the EU is declining’

OMG! Trade with the EU is declining?! Tomorrow, our trade with them will be nothing! We must end all commerce with them now!

That’s clearly the reaction this claim was designed to elicit, and there were enough people lacking either the ability or the inclination to check it that it succeeded in its goal.

While it wasn’t one of the primary arguments advanced by the Leave campaign, it’s a drum that rightwing politicians, commentators and newspapers have been beating since day one. It was also one of the central planks of the “failing EU” narrative, which you still hear to this day.

Still, if the UK’s trade with the EU is shrinking, surely it’s a point worth making?

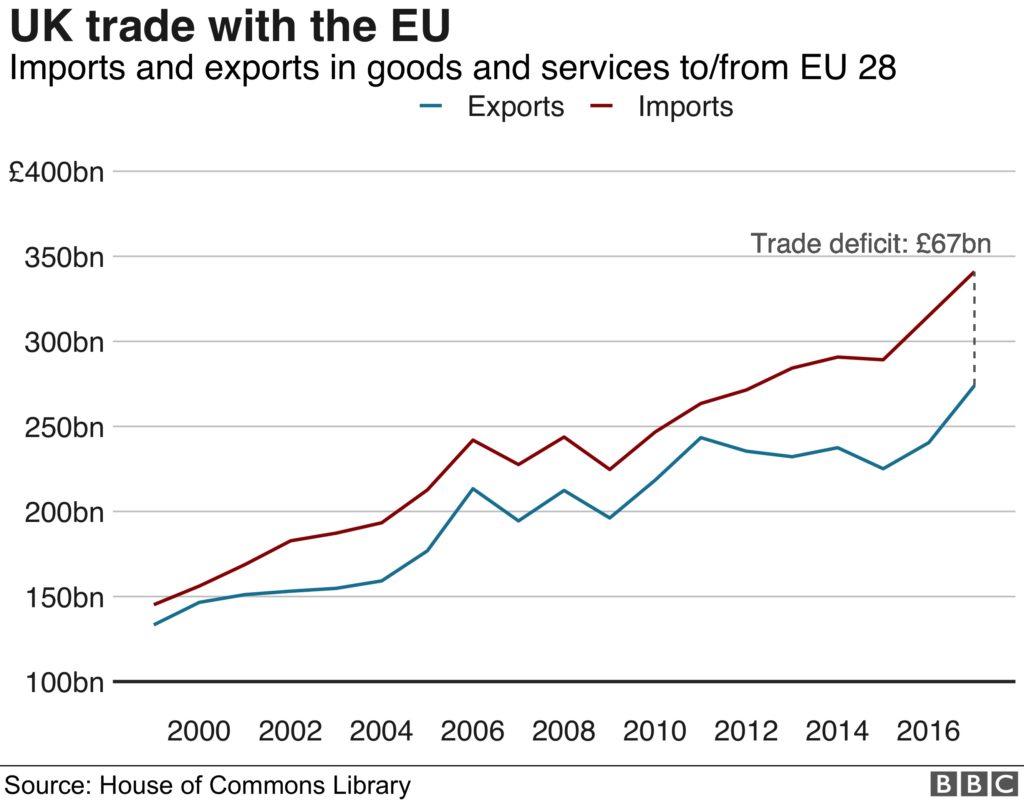

The first problem here is that the statement is not true. UK trade with the EU has grown steadily since we joined, as even House of Commons figures show:

Which shouldn’t come as a colossal surprise, as these are our closest neighbours, with whom we have enjoyed ever closer ties for almost 50 years. Of course trade with them is always going to grow.

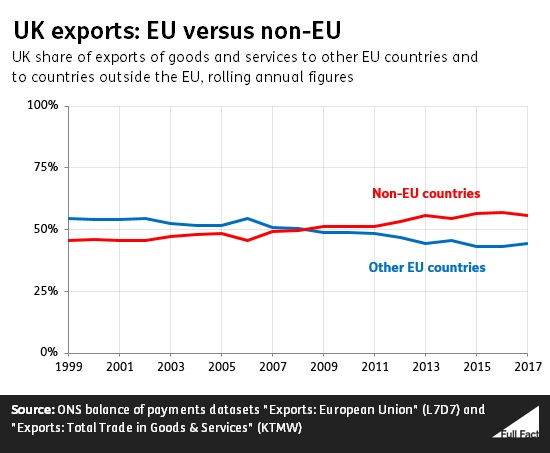

So what is Thickinson wittering on about? It turns out what she meant is that the UK’s trade with the EU as a proportion of its overall trade has been decreasing (slowly) since 2000. Trade with the EU is still growing, but trade with other countries is growing faster.

(The trend was bucked in 2019, when the share rose to 46%, which is why they bit their tongues on this one for a while.)

So, not exactly a precipitous decline, but if trade with the EU as a proportion of overall trade is shrinking, shouldn’t we be a little worried?

Well, no, for two reasons.

First, trade outside the EU has increased precisely because of EU trade agreements with other countries and blocs, such as Israel, Egypt, South Africa, Canada, Mercosur and South Korea. In other words, trade with the EU has (proportionally) fallen because of trade through the EU. (For the benefit of those who have been living under a rock for five years, the UK will cease to be a signatory to all those deals as well as its EU agreements from January 1 2021. Sure, we might renegotiate some after exit, but there’s no guarantee of that, and even if we succeed, they’ll almost certainly be on less favourable terms, as the UK now has a lot less negotiating clout than it did as part of a bloc of 510 million people.)

Second, the countries with which the UK’s trade is growing more quickly are on the whole much smaller; they are developing countries. Trade with developed nations, and with nations with which trade relations are already well established – such as those in the EU – is never going to grow particularly fast, because it’s all grown up already.

Let’s take, as a hypothetical example, the nation of Arsendia. If you were to tell me that trade with Arsendia had increased by 1,000% over the past year, while trade with the EU 27 had grown by only 0.2%, I’d think, “Whoa! Maybe Arsendia is the future!” But if I then discovered the somewhat relevant supplementary information that trade with Arsendia this year was worth £110, compared with £10 in 2018-19, while the value of trade with the EU stood at £668bn, I might come to a slightly different conclusion.

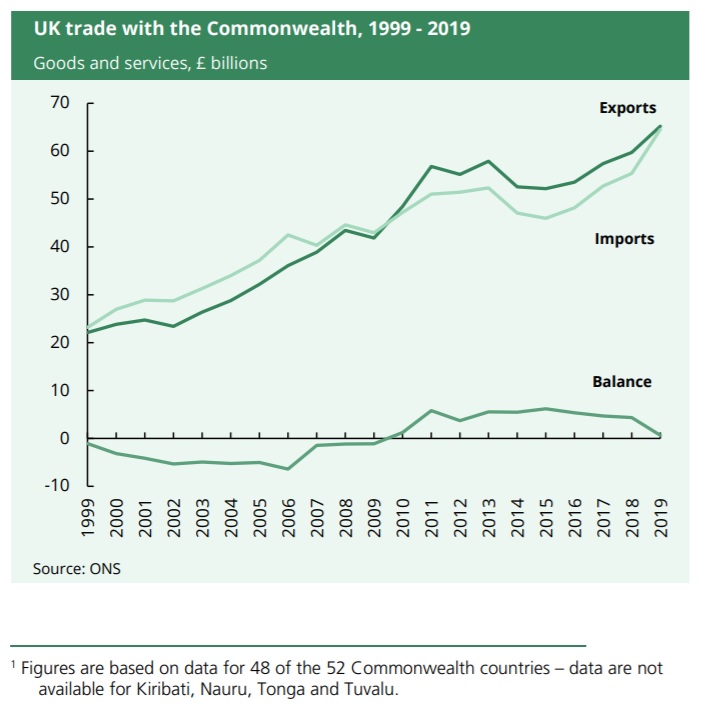

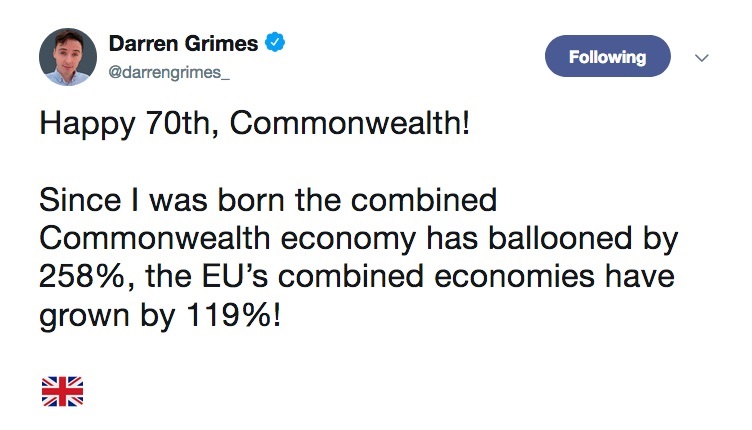

To take a real-world example often cited by Brexiters, over the last 20 years, trade with Commonwealth nations has increased by a factor of more than three.

Meanwhile, over the same period, the value of UK trade with EU countries has merely doubled.

But now look at the absolute figures. Exports to the EU in 2019 were worth £300bn (43% of the UK total), and imports from it £372bn (51%). Meanwhile, UK exports to all the Commonwealth nations combined in 2019 were worth £65.2bn, while imports from those countries had a total value of £64.5bn. That’s less than a fifth of the EU total.

Again, pretty much what you’d expect when countries tend to do most of their trade with their neighbours, and most Commonwealth countries are half the fucking world away.

Adversely comparing the rate of growth of trade with established trade partners with the rate of growth of trade with tiny, brand-new buddies is the equivalent of a father taking a tape measure to his 18-year-old son and 14-year-old daughter, then saying, “Sorry, Kev, but Lisa’s grown three inches this year and you’ve barely sprouted at all, so I’m afraid she gets all the attention now.”

This is a common statistical misapprehension called the base rate fallacy, or ignoring the baseline. Expect it to make a reappearance, as it is one of the populists’ favourite subterfuges.

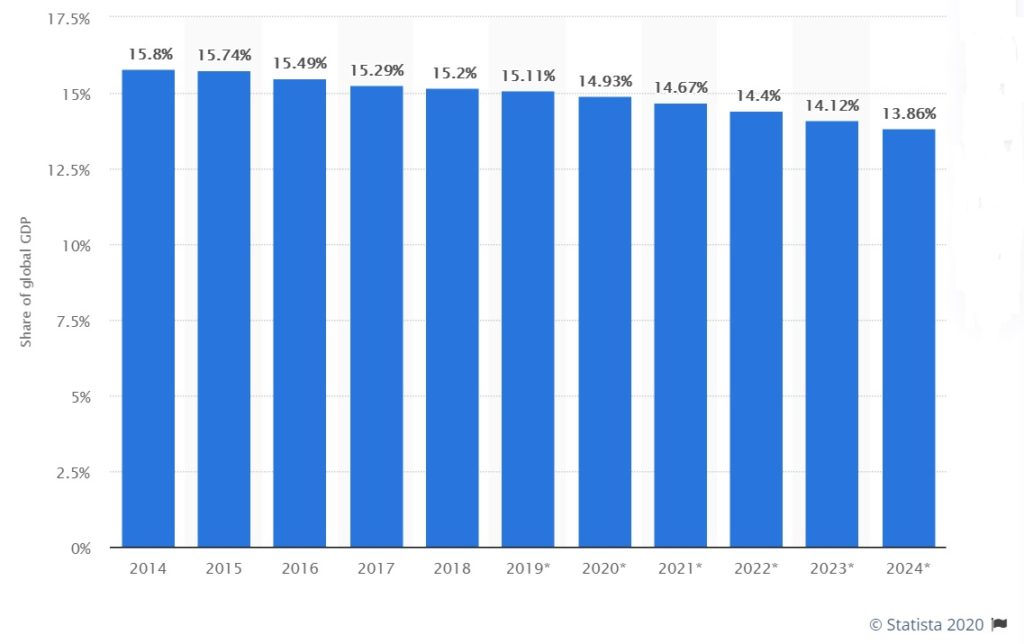

(The United States’ share of global GDP is declining for the exact same reason – less developed nations are eating up the pie because they have more scope to expand quickly – but you won’t find any of the Brexit zealots shouting about that.)

Let’s try to boil this down into something so simple that even the average Tory MP can understand it. Trade with the EU is growing. Trade with some other, much smaller countries is growing a little faster, because they have more capacity for growth, but that’s unlikely to continue for long. The EU, the UK’s closest neighbour, is, and will always remain, the UK’s most important trading partner.

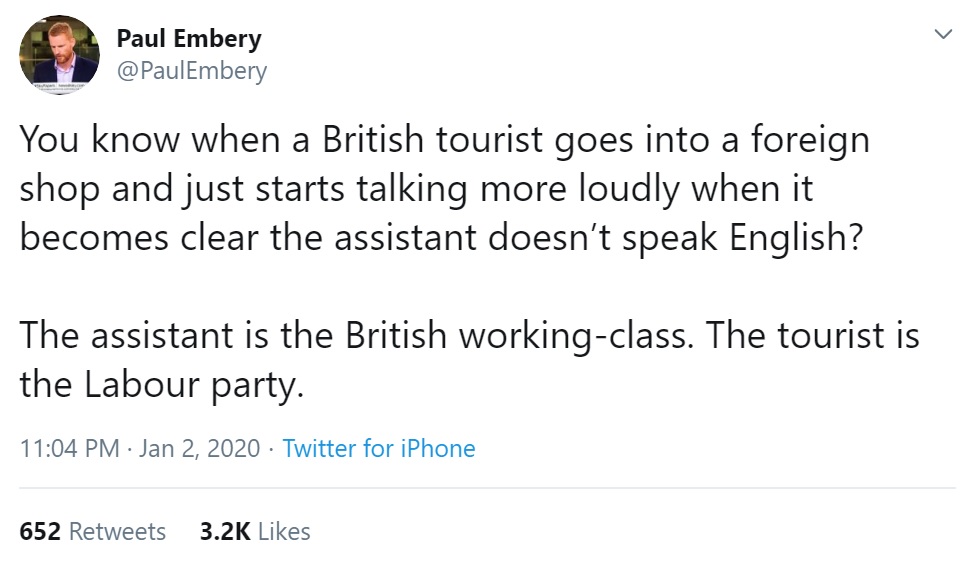

A recurring theme of these posts is going to be: whenever you see pat statistical statements like Dickinson’s, by politician or commentator or journalist, they are not giving you the full picture. It’s not necessarily their fault – there isn’t enough space. But the space shortage gives them an excuse to Instagram the data; to present only the facets of the information that best supports their agenda.

For a full understanding of the situation, you need to a) read beyond the headline or tweet, and ideally trace the source of the data; b) do further research, or at least read some rebuttals; and if neither of those is possible, c) ask questions. In the particular case of “Trade with the EU is declining’”, the relevant questions would be: “What level is it declining from?”, “How fast?”, and “Is this trend likely to continue?”

As we’ll see time and again in the coming posts, without the proper context, numerical information is useless. However great the emotional impact on you, you must not draw any conclusions until you see the wider picture. If you can’t overcome your fear of numbers, you must at least stop meekly accepting them.

Next time: let’s fund the NHS instead!