“Some folks set a powerful store by this here eddication, but I tell y’all right here and now that readin’ an’ writin’ an’ cipherin’ ain’t never got no sinners into Heaven yet!” – Evangelical Missouri preacher quoted in Ozark Folk Songs vol IV, ed. Vance Randolph (1949)

We’ve established, over the last few posts, why quite a few folk have “had enough of experts”, and some of the mechanisms by which rationalism is being undermined. One question we haven’t considered is this: who do they want running the show instead? Fine, so you’re anti-intellectual; but what are you pro?

Many don’t seem to have thought that far ahead. All they know is, the technocratic status quo isn’t quite to their liking, and they want it gone pronto, consequences be damned. Leave the EU with no deal! Lock her up!

But abandoning ship in the absence of even a makeshift lifeboat is criminally reckless. That’s why so many Britons are still so passionately opposed to leaving the EU; we haven’t heard any better ideas yet. Wishy-washy promises of a socialist utopia, or a “global-facing Britain”, both entirely dependent on variables over which we have little control, will not do. We want a detailed bloody plan.

Some give off the impression that they just want things to be like they were; before the EU, before all those horrid forriners moved in. But they’re overlooking three things. First, the hardships of life before 1973: lower living standards, labour disputes, moribund industries, high inflation, dwindling resources, diminishing world influence. Second, the rest of the world has moved on; the UK no longer enjoys the democratic, technological or military superiority it once did, and in this dynamic, hyperconnected world, the best way to survive is to maximise your international ties, not sever them.

Third, you can’t just wave a magic wand and undo 46 years of structural change. The UK’s economy is now intricately woven into the EU and the wider world, and if you just rip it out lickety-split, it will, quite simply, stop working.

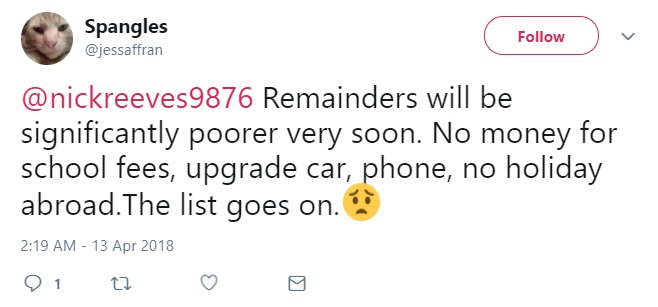

Only one realistic alternative to technocracy has been proposed, but you won’t find any manifesto spelling out its methods or aims. It exists only in half-lit corners, in fragments of tweets, at the tail end of flip insults.

Kirk versus Spock

To explain, I’m going to bring in another book (sorry, Brexiters). Thinking Fast and Slow, published in 2011, is a tour-de-force roundup of the work of psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. At the risk of doing Kahneman a disservice, his thesis is essentially that humans have two primary modes of thought: he calls them system 1 and system 2.

System 2 is deliberate, reflective, analytical; it involves focus and application. It’s what we mean when we say we’re “putting our thinking caps on”. We use it to tackle novel or complex problems, to carry out complex calculations, to make long-term plans, and learn skills. Most of its operations take place in the prefrontal cortex, the newest, most uniquely human part of the brain.

System 2 is also creative, original, often brilliant. The catch is, it’s slow – and takes a lot of effort. It monopolises valuable resources (because when you’re focused on one task, you can’t undertake any others). Improvising a speech, writing a play, attacking a mathematical problem: few can sustain these activities for long without a break. As a result, we do all we can to avoid engaging system 2 thought, particularly as we get older.

The good news is, we don’t have to – because we have a spare brain.

System 1 has none of system 2’s hangups. It is quick, bold, almost effortless. It’s what we’re using when we talk about doing something automatically, or “without thinking” (we are thinking, of course – we’re just not conscious of it). What’s more, it’s remarkably good at a vast range of tasks. Estimating distances, locating sources of sounds, pattern recognition, basic arithmetic, completing common phrases. System 1 can even – after lots of practice, for which it is admittedly indebted to system 2 – manage complex functions like playing the piano and flying a plane.

But speed comes at a price. The reason system 1 is so snappy is that it uses a lot of short cuts. Because its functions are centred on the amygdala – one of the oldest parts of the brain, the part we share with lizards – its deductions and decisions are rooted in instinct and emotion rather than reason, and thus can be wildly off the mark.

(If I have one bone to pick with Kahneman’s book, it’s that “system 1 versus system 2” isn’t a terribly memorable opposition. So henceforth, I shall refer to system 1 – the the old-fashioned, impulsive, combative brain – as Kirk, and system 2, the more modern, analytical brain, as Spock.)

Kahneman spends much of his book detailing Kirk’s commonest cockups – the cognitive biases. I’ve covered these in a previous post, but those that crop up most in online discussions are the third-person effect (“My opponent has fallen for lies but I haven’t”), the projection illusion (“Most people act like me, for the same reasons as me”), the slippery slope fallacy (“Soon we’ll all be under sharia law!”), the sunk cost fallacy (“We’ve come this far – we can’t turn back now”) and the availability heuristic (“I’ve seen or read about this behaviour, so it must be everywhere”).

Essentially, humans have two different operating systems, with complementary strengths, suitable for different situations. One is great for getting you through everyday tasks and dire emergencies; the other is better for novel quandaries and counterintuitive problems.

As fascinating and rigorous as Kahneman’s book is, it is, in a way, just a restatement of an age-old theory. Ideas about the duality of mind date back at least to the concepts of chokhmah and binah in the 13th century and run on through instinct and reason, conscious and subconscious, to id and superego.

So what’s all this psychobabble got to do with the common fisheries policy? Look back at the description of Spock thinking. Reading, problem-solving, creative solutions, learning: it’s basically the operating manual for an intellectual.

Academics, experts and their ilk don’t only use this mode of thought. We all have access to both Kirk and Spock; they are what makes us human. What differentiates one person from another is not their access to these systems, but the frequency and efficiency with which they use them. Genetics may play a part, but there’s little doubt that education is a decisive factor.

People who have read more widely, who have studied to a higher level, travelled more widely, mastered a skill like a language or a musical instrument, or spent more time solving problems or creating things, are more likely to have a well-developed Spock brain, and to use it in a wider range of circumstances.

Meanwhile, those who aren’t so in touch with their Spock side – because they didn’t go to university, or learn a language – prefer, wherever possible, to stick to Kirk.

“As popular democracy gained strength and confidence, it reinforced the widespread belief in the superiority of inborn, intuitive, folkish wisdom over the cultivated, oversophisticated, and self-interested knowledge of the literati and the well-to-do” – Richard Hofstadter, Anti-Intellectualism in American Life

Just plain folks

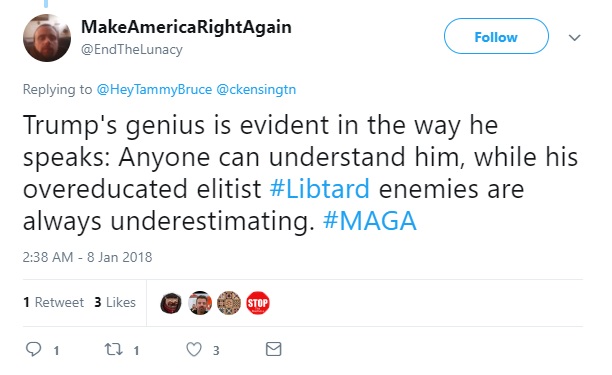

One of the crucial factors in Donald Trump’s appeal seems to be his gift – in the eyes of just enough American voters – for “telling it like it is”. An exit poll taken during the South Carolina Republican primary, for example, reported that 78% of those who rated “tells it like it is” as the top quality in a candidate planned to vote for Trump.

For non-Trump supporters, this is flabbergasting. Few of us could name anyone who tells it less like it is. It’s a documented fact that Trump has told an average of six lies for each day of his presidency. So what do they mean by this?

I think what they love about Trump is not his laser accuracy or his staggering genius, but his simplicity. He tells it not like it is, but like they wish it was, breaking every problem down into a formula so basic that they can absorb it without breaking sweat.

Kahneman might translate thus: “Donald Trump speaks to me in my language. He offers solutions simple enough for me to understand without effort, in words simple enough for me to understand without effort.” In other words, this is a Kirk-dominant brain communicating in a way that is perfectly clear to other Kirk-dominant brains. And the language it is using is common sense.

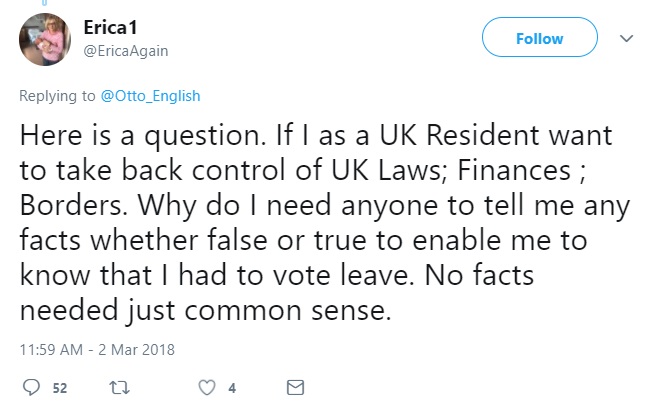

Common sense. The rallying cry rings out again and again and again across tabloid editorials and the social media battlefield.

Their passion is not wholly misplaced. As we’ve seen, the system 1 brain, honed over millennia, is a perfectly good remedy to many problems. You sure as hell don’t want to be hanging around engaging your Spock when there’s a rock hurtling straight at your head.

Their passion is not wholly misplaced. As we’ve seen, the system 1 brain, honed over millennia, is a perfectly good remedy to many problems. You sure as hell don’t want to be hanging around engaging your Spock when there’s a rock hurtling straight at your head.

But in the wrong situations, common sense is poison. Its ingrained cognitive biases make nuance and compromise impossible. Kirk is abysmal at performing cost-benefit analyses and hopeless at planning for the long term. While going with your gut might serve you well in a live combat situation or on a frenetic trading floor, it’s a downright liability when it comes to negotiating intricate trade deals, eliminating terrorism, or persuading a rogue state to abandon its nuclear research programme.

When confronted with unfamiliar problems, ones that Kirk is not best equipped to deal with, lizard-brains react in one of three ways: fight, flight, or give up.

The first two are apparent in just about every one of Donald Trump’s policy decisions. Drain the swamp (fight). Build the wall (flight). Lock her up (bit of both). And 99% of his Twitter diplomacy consists of hamfisted playground insults and threats. The man is literally incapable of a measured response.

The third reaction is interesting.

Armchair critics

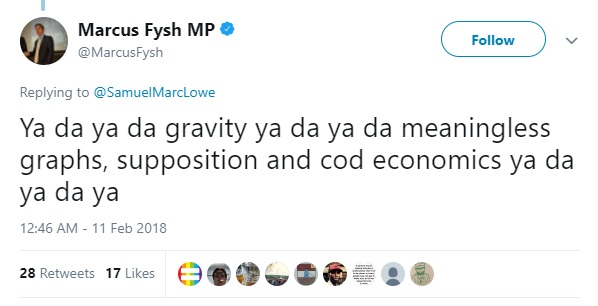

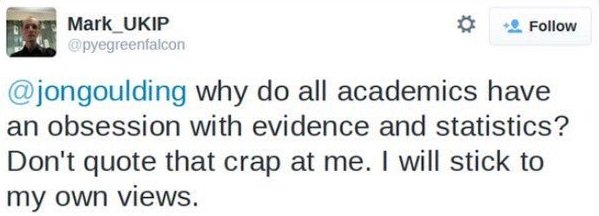

One of the things that has struck me most during my online interactions with Brexiters is how little work they are prepared to put in. Few lifted a finger or eyelid to inform themselves about the pros and cons of EU membership before the referendum, and the number has scarcely been augmented since. When responding to statements they disagree with, they seldom elaborate beyond “You’re wrong”, “Bollocks”, “Nonsense” or “Yawn”. If you send them a link to an article to back up your point, they rarely click on it, and when they do, they don’t read past the headline.

As for creative phraseology, forget it. They talk almost exclusively in clichés and slogans, and their “arguments” are all ripped verbatim from Farage or the Express. This is why it’s sometimes so hard to distinguish Brexiters from bots.

Tempting as it is to write off all diehard Brexit and Trump voters as stupid, that might be an oversimplification. My theory is that because their Spock brains are less developed, analytical thinking is even harder for them than it is for the rest of us, and so they’re even more likely to avoid it. They just prefer to use their Kirk, even when it’s clearly not the right equipment for the job. They’re not dumb, necessarily; just intellectually lazy.

Revenge of the pointyheads

Many people still seem to revere common sense as an unalloyed good, a panacea. It is not. Different operations call for different tools, and Kirk is painfully limited in scope. (For a good summary, read this.)

Common sense dictates* that you should run away from a bear. Don’t; you’ll die. Common sense dictates that you should throw water on an electrical fire. Don’t; you’ll die. Common sense dictates that you are safer with a close family member than with a stranger. You’re not. Common sense dictates that letting your anger out is good for you, that time passes at the same rate for everyone, regardless of velocity, that you can ascertain both the speed and location of an electron at any one time. Common sense dictates that you do not inject someone with a mild strain of a disease in order to prevent them from contracting a potentially fatal type.

(*Telling little phrase, that. Reason doesn’t dictate anything; it simply states.)

Common sense was all very well when humans scavenged on the savannah, and it served most of us adequately until quite recently. But it has always been our ability to reason that separated us from the animals, allowing us to create, to hypothesise, to codify, to pass on knowledge and, crucially, to specialise.

Common sense has had millions of years to eliminate war, terrorism, poverty, disease and famine, and it has failed miserably. It’s only since the Enlightenment broke its chokehold that humanity has begun to address those issues. And in this insanely complex modern age, when the amount of knowledge required for society to function is a thousandfold greater than any one person could hope to take in, the need for uncommon sense – ie, experts – is greater than ever.

The historical trend is undeniable: slowly but surely, Spock thinking is displacing Kirk, correcting its cognitive biases and giving us more effective solutions to our problems. Advances in medical science, the steady increase in the standard of living, the lengthening human lifespan and the gradual decrease in the rate of violent crime are all testament to this.

Now, perhaps resentful of this encroachment on their territory, the lazy lizard-brains have reared up. In a campaign unlikely to be of their own devising – I’ll save the speculation as to who might be responsible for my next post – they are sidelining, shouting down and smearing voices of reason at every turn.

It’s time to return fire. But I’m not suggesting that we try to eradicate common sense. We can’t – it’s an inalienable part of our makeup. But we do need to dispel this pernicious notion that gut feeling is the answer to everything; to escort Kirk out of the delicate galactic peace negotiations, pack him off to some distant planet with lots of slimy aliens to punch and green-skinned women to boink, and let Spock handle the tricky stuff.

Thanks, Lu.

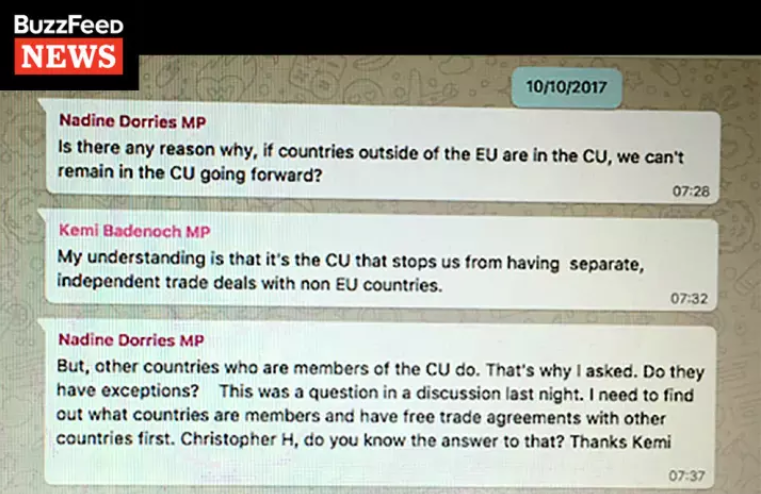

Nadine Dorries (MP!) came in for a lot of stick for her assertion that the vote to leave the EU was correct

Nadine Dorries (MP!) came in for a lot of stick for her assertion that the vote to leave the EU was correct