A world without pronouns would be a tedious one. “Bryan Fielding was an ordinary man. Bryan Fielding did not think of Bryan Fielding as an ordinary man, but Bryan Fielding most certainly was.” Pronouns save us time by avoiding the need to spell out the objects of our utterances in full at every mention.

A world without pronouns would be a tedious one. “Bryan Fielding was an ordinary man. Bryan Fielding did not think of Bryan Fielding as an ordinary man, but Bryan Fielding most certainly was.” Pronouns save us time by avoiding the need to spell out the objects of our utterances in full at every mention.

But they can be slippery blighters.

When I use the word “I”, you have a pretty good idea of who I’m talking about. With a bit more context (where you are, who you’ve been talking about), the same goes for “he”, “she” and “they”. Minor confusions can arise in sentences like “When Sara kissed Barbara, she felt amazing”, but things are usually clear enough.

“You” is a trickier proposition. If I address a statement to “you”, I might be talking to you and you only, to you and others present, or to you and others of a group of which I consider you a member who are not present. Those who have studied foreign languages will know that while English lumps all these possibilities together, other tongues admit more distinctions: the French tu and vous, the German du and Sie.

But of all of personal pronouns, by far the biggest potential troublemaker is “we”.

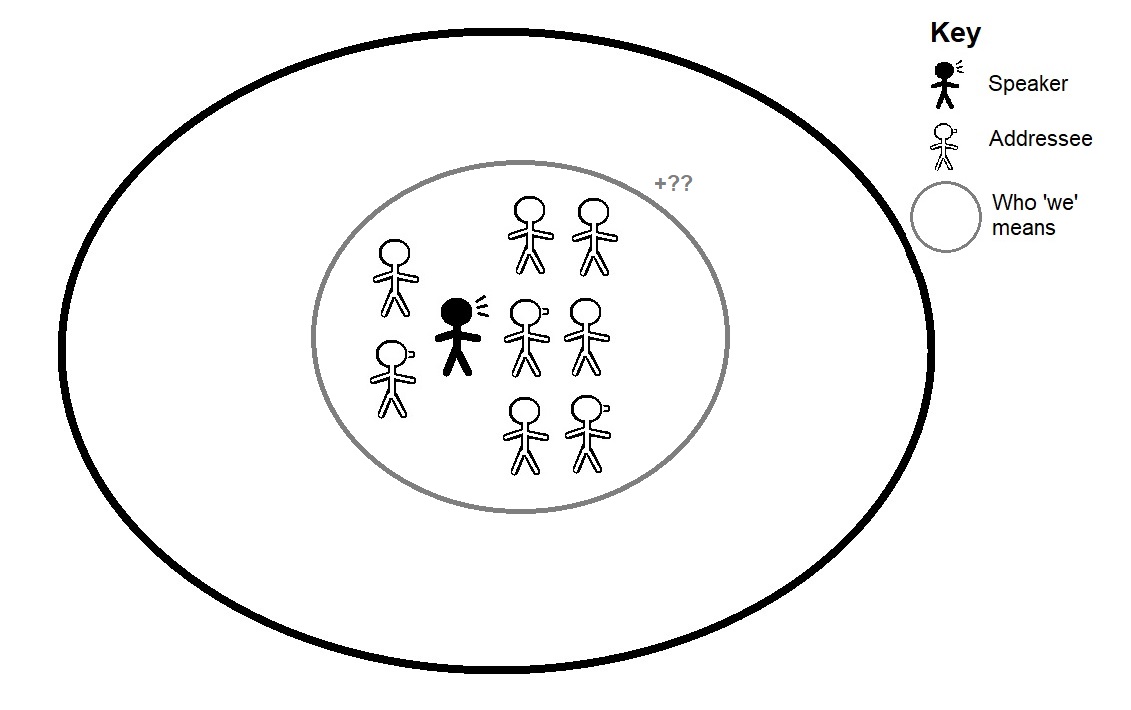

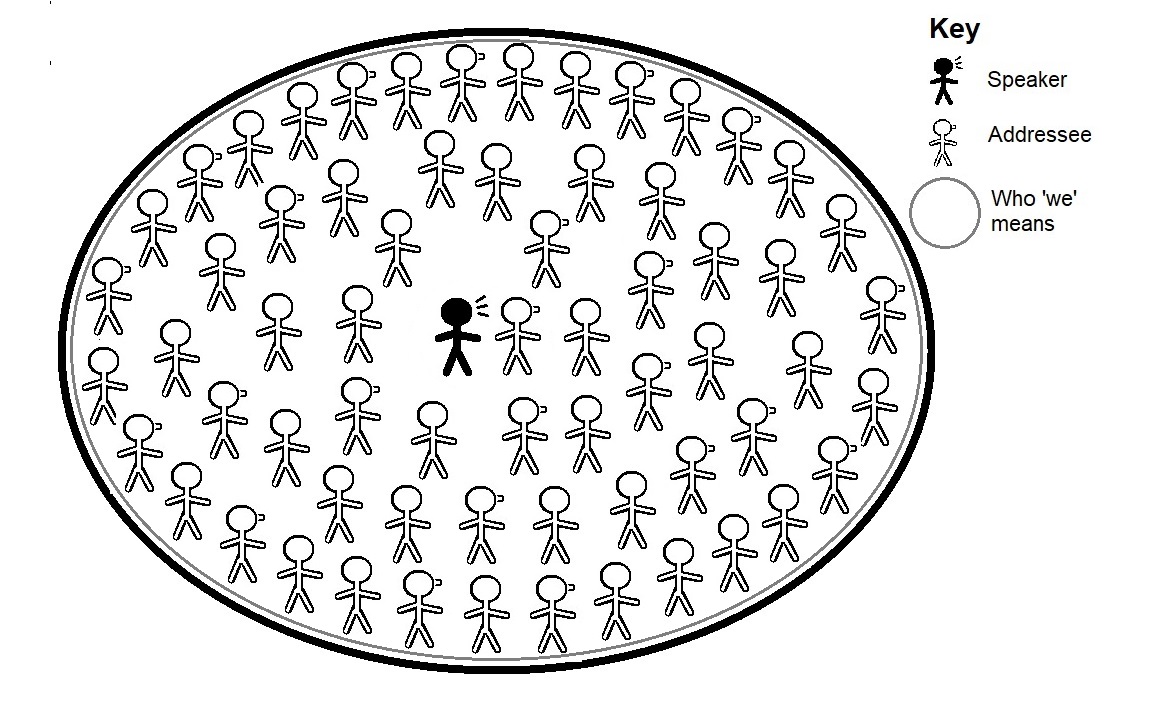

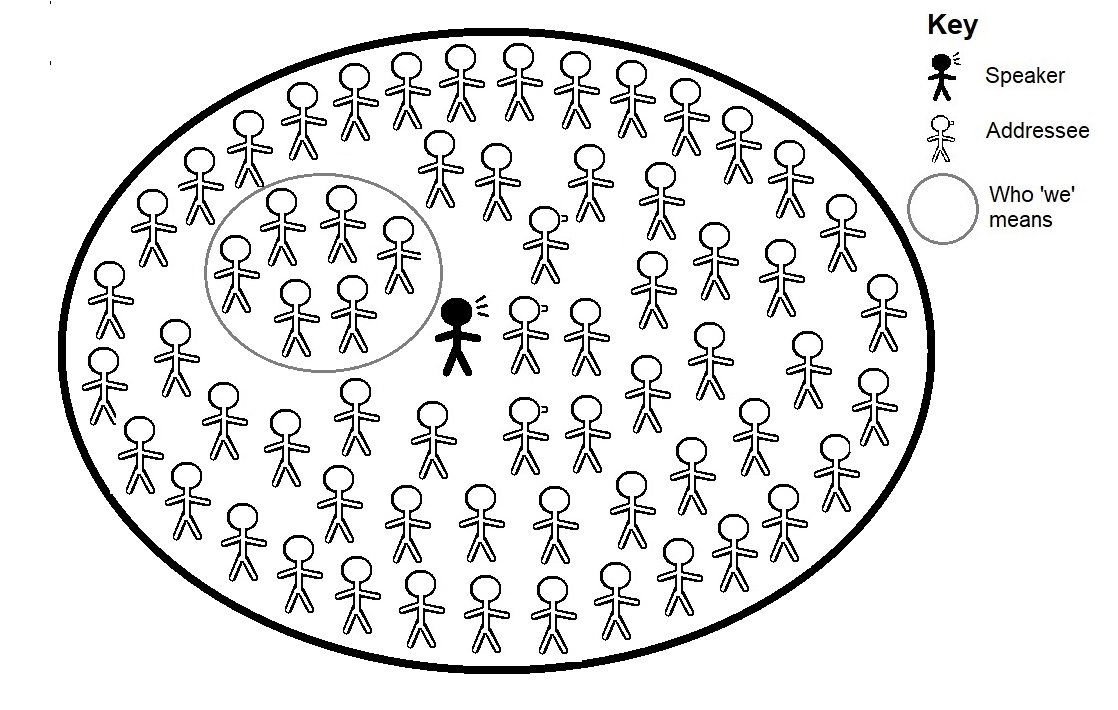

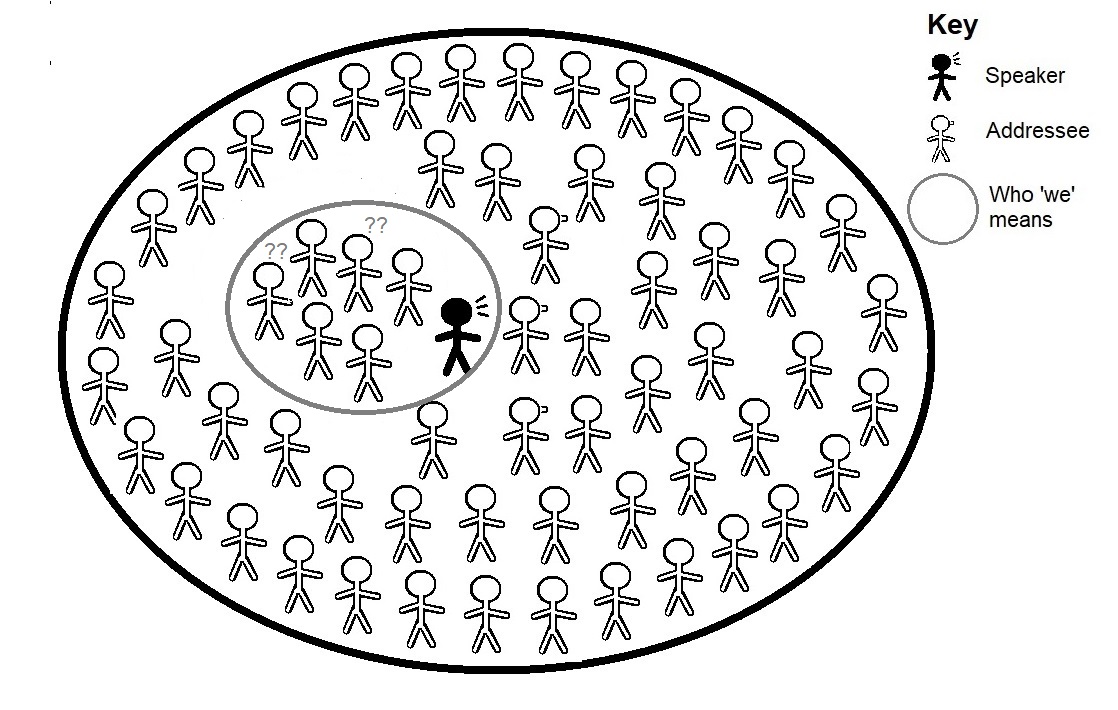

Without any context, all you can be sure of when someone says “we” is that they mean “me, plus at least one other individual” (and even then you’ll still be wrong some of the time). This may or may not include any or all present; it may include only one other person, or it may stretch to every other human being who is living, has lived, or is yet to be born.

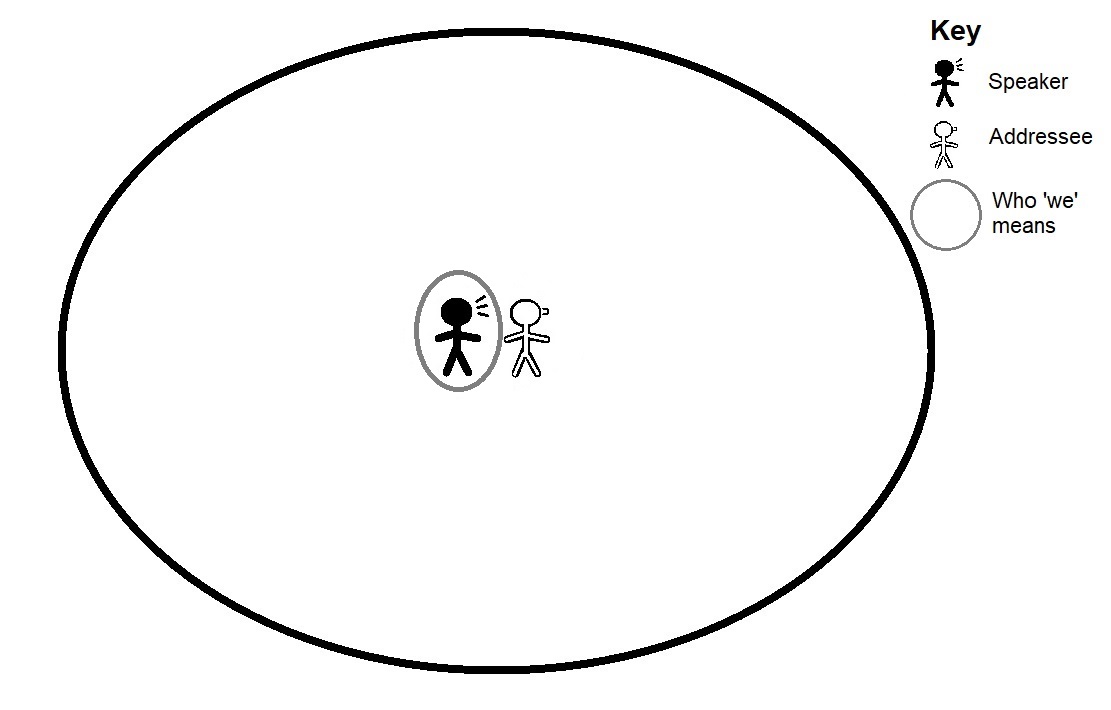

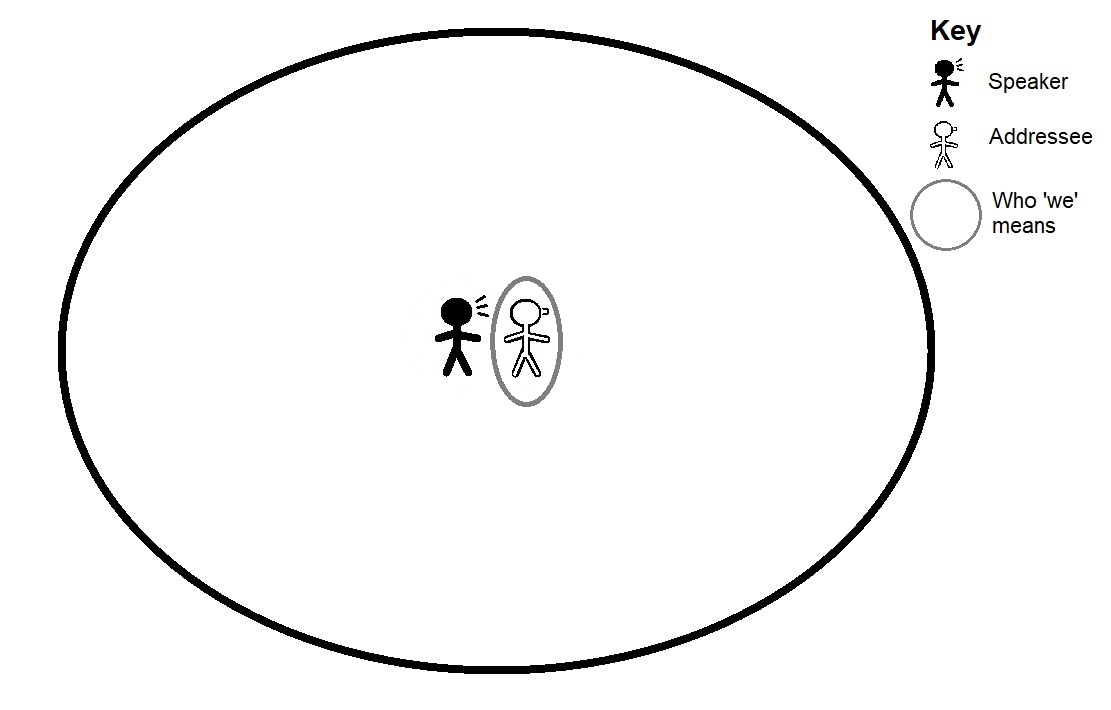

But the crucial ambiguity – and one that populist demagogues have gleefully exploited – is this: “we” may include or exclude the person being addressed.

Some examples to show you what I mean.

1. “We are not amused”

I’ll get two special cases out of the way first, as although they’re not especially relevant to my argument, they’re fascinating.

The “royal” we, meaning “I”, while associated most closely with Queen Victoria, has actually been with us for almost a millennium. Depending on who you believe, the first to use the word this way was either Henry II or Richard I, and its intended signification, apparently, was “God and I” – ie it was an attempt by the monarch to shore up his authority by claiming a “special relationship” with Him Upstairs.

It soon spread by contagion to anyone who overrated themselves – Margaret Thatcher was widely lambasted for her comment, “We have become a grandmother.”

2. “How are we feeling today?”

This “doctoral” we, also sometimes heard from carers of small children, actually means “you”. It’s a trick GPs, specialists and other “responsible adults” use to put the patient or child at ease from the off by creating a sense of affinity.

3. “What shall we do tonight?”

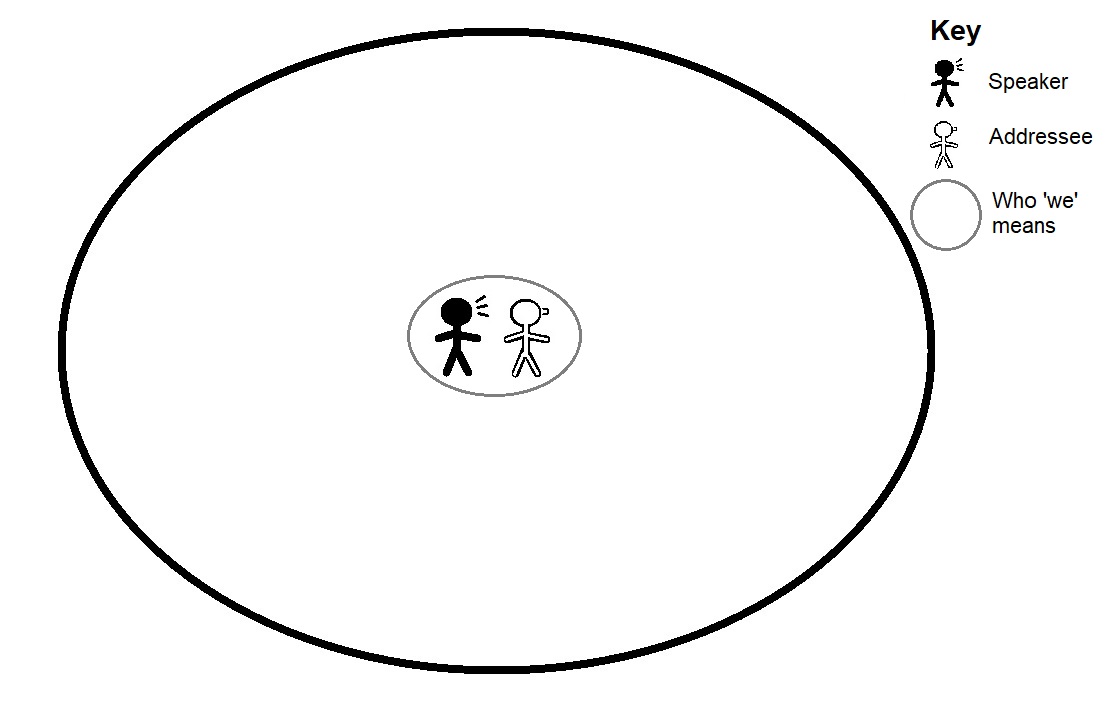

The most basic meaning of “we” is “the person speaking plus the person they are speaking to”, namely “me” and “you”.

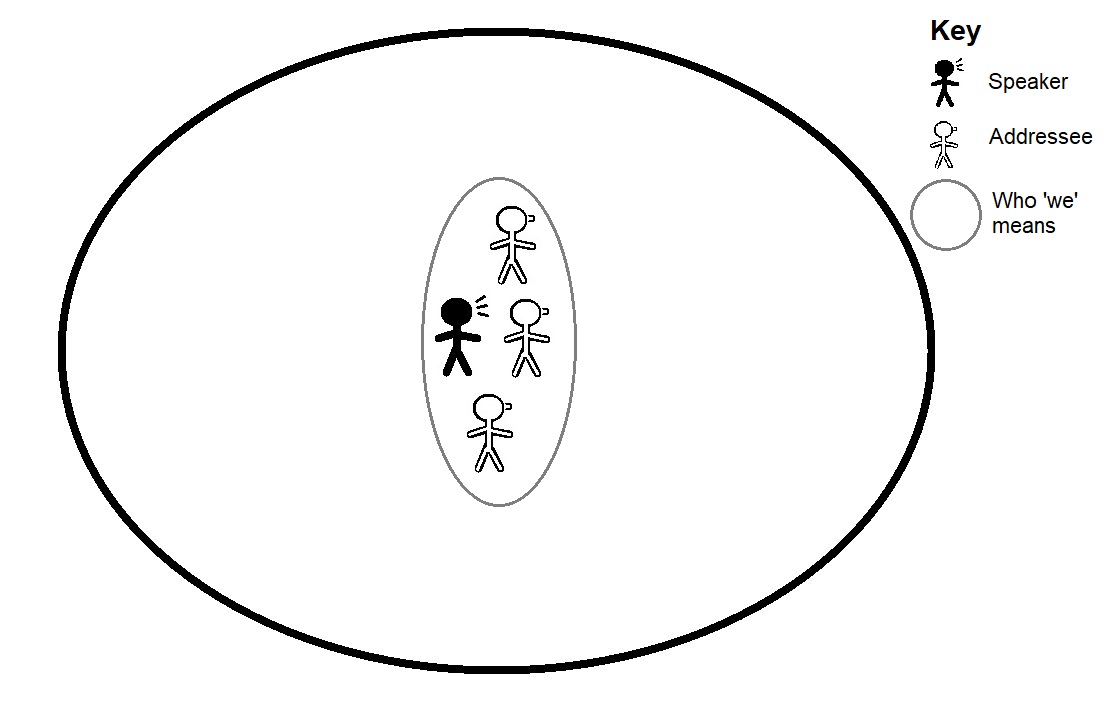

4. “We are gathered here today …”

Ever since the first human ancestor ululated from a treetop, it’s been possible to address more than one individual at a time. Now, in the era of mass communication, you can talk to millions.

5. “Sorry we’re late”

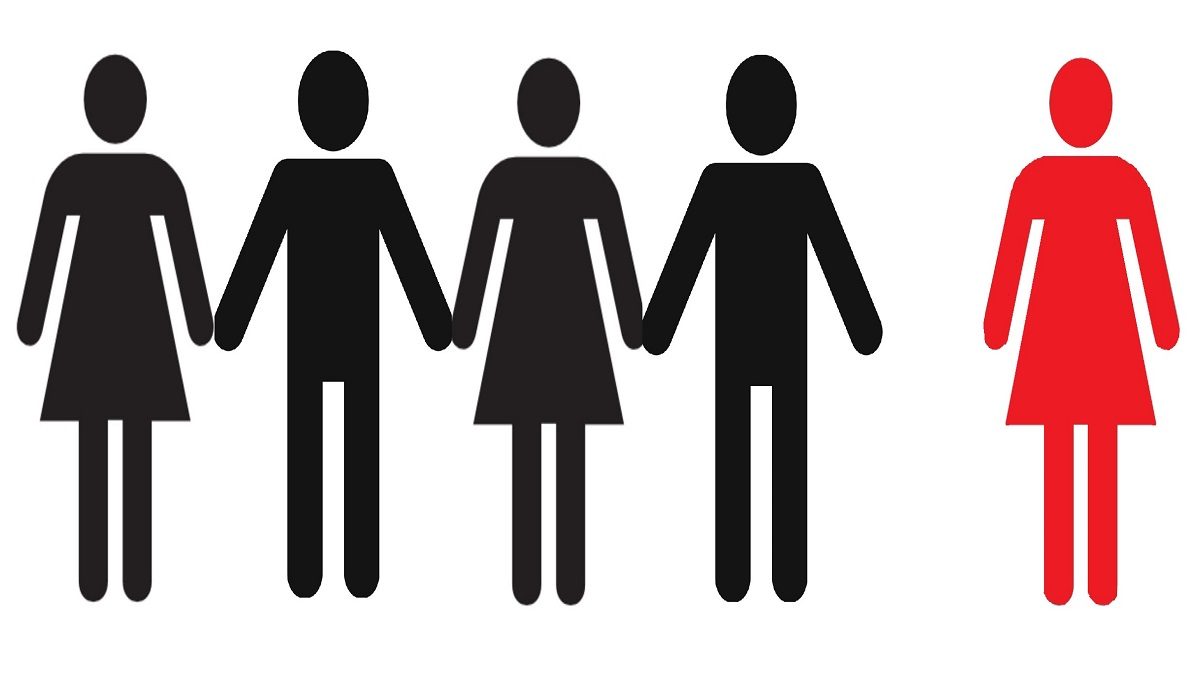

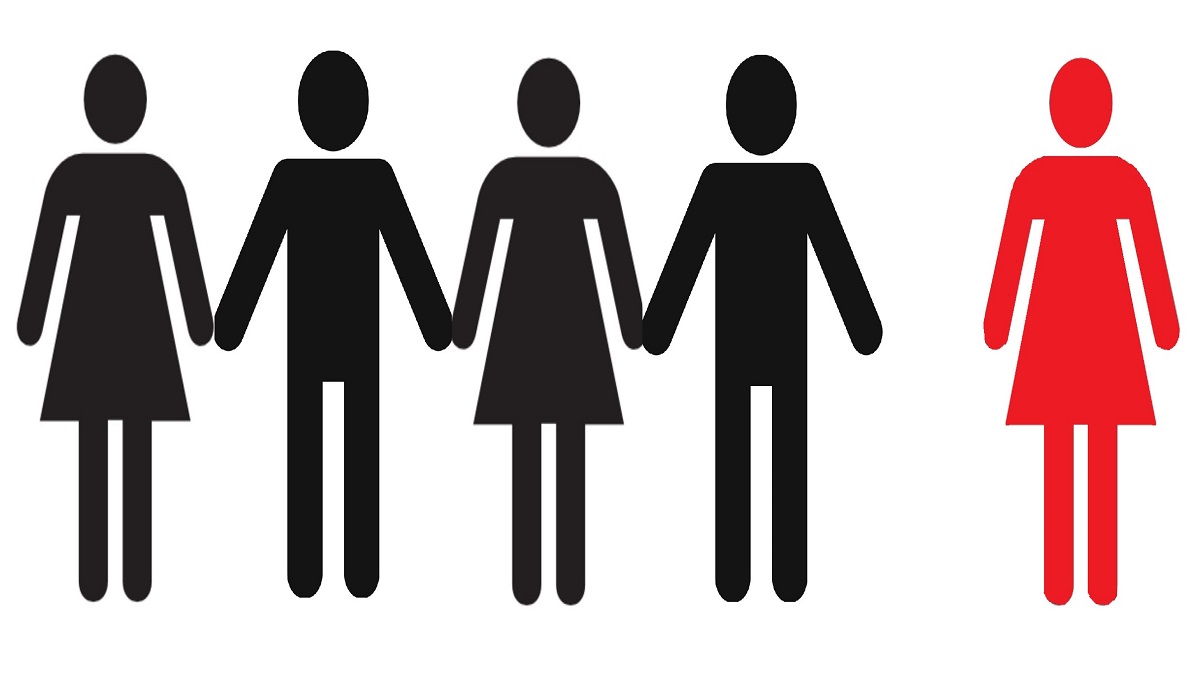

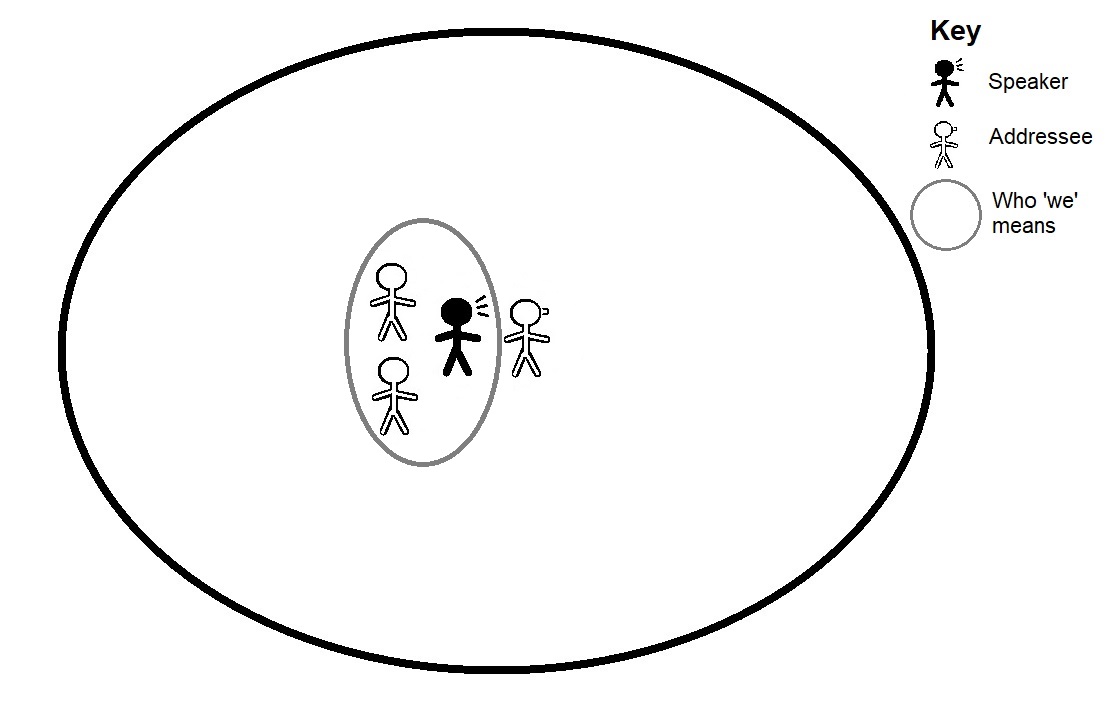

The second simple meaning of “we”, again mostly restricted to real-life applications, has a radically different meaning from no 3: it’s “me, plus another person or persons, and explicitly not you”.

6. “We know from Godel’s second incompleteness theorem …”

The academic we, used in dissertations and other research literature, is frowned upon by most pointy-heads these days, precisely because it presupposes the reader’s agreement. “We” should strictly refer only to the authors of the study, not to “the scientific community” or “people in general”.

7. “We are destroying the planet”

What you might call the “Attenborough we”: generally taken to mean everyone; humanity as one monolithic mass. Can be extended to denote all humans past, present and future: “As a species, we do not know what our legacy to the universe will be.”

8. “We’re gonna win the league”

In the above cases, the referents of “we” are generally very clear (while the first two cases are a little odd, they are agreed by longstanding convention). There’s no potential disparity between who they actually mean when they say “we” and who you understand them to mean.

In the above cases, the referents of “we” are generally very clear (while the first two cases are a little odd, they are agreed by longstanding convention). There’s no potential disparity between who they actually mean when they say “we” and who you understand them to mean.

But now we’re entering murky territory. How can this 20-stone football fan, who hasn’t kicked a ball in anger since 1987 and whose sole contribution to match strategy has been to bellow “Useless wanker” at the team’s left-back, possibly claim any ownership of the on-field players’ success?

What he is signifying by “we” here is the team, or the club, that he supports, rather than himself and his Stella-swigging friends in the Fyffes End. He feels a connection to the club, even though his contribution is limited to a few hundred quid a year in season tickets and foul-mouthed support from the sidelines.

The club itself, assuming he hasn’t disgraced himself by throwing coins at the opposition goalkeeper, barely knows that he exists. But when that trophy comes home, he celebrates just as wildly as if he were the team’s veteran captain.

This is the chief appeal of tribalism: the ability to opt into and out of whatever aspects of membership you see fit. Your responsibilities within the tribe are minimal, and yet you feel able to take your share of the credit in the event of a victory.

9. “We won the war”

If you were a 95-year-old who served in the North African campaign, you might be justified in claiming a small part of the acclaim for Britain’s victory in the second world war (along with millions of Russians, Americans, Chinese, Indians, Poles, Aussies, Kiwis, French, etc). But as a fat middle-aged loser from Coventry who was born in 1963, you absolutely cannot.

What this old bigot means to be understood by “we”, of course, is all British people who have ever lived and will ever live. There is no such thing as an “innate British character” that you simply pick up by virtue of being born in these isles.

It also raises the question, how far back does Britishness go? To the Empire? To the Norman kings? To King Alfred? To Boudicca? And where do conscientious objectors, traitors, naturalised immigrants, and anti-Brexit liberals fit into your “we”?

Wars these days are fought on values, not nationalities. It’s difficult not to conclude that, were the same conditions of 1945 to emerge today, this old bigot would pick the other side.

10. “We don’t like strangers round here”

The speaker presumes to speak on behalf of all members of a group, when in fact their view may not be universal or even widespread.

The speaker presumes to speak on behalf of all members of a group, when in fact their view may not be universal or even widespread.

There is undoubtedly a malicious element to this “confrontational we” – it is after all an attempt to intimidate by suggesting that the speaker has extensive support. But there may not necessarily be any deception involved; the speaker may well believe, correctly or not, that everyone else thinks the same way he does.

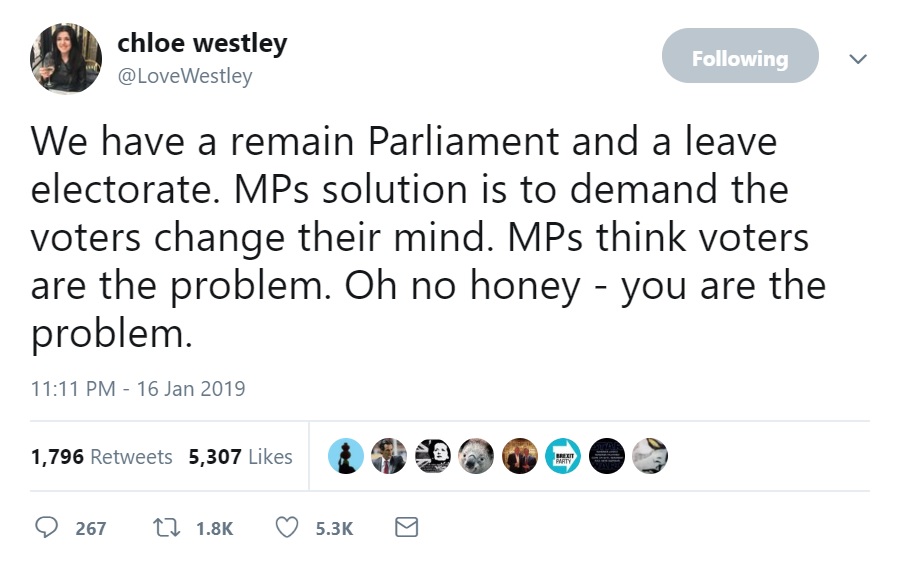

11. “We have a remain parliament”

Permavictim rentagob Chloe Westley of the TaxPayers’ Alliance has no such defence. When she says “we” here, she wants Brexit voters to believe that she is on their side. For one thing, she’s Australian, so not even part of the group she claims membership of. For another, she’s paid by US corporations to spread falsehoods in order to secure a damaging no-deal Brexit that will actively harm British citizens and facilitate the sell-off of public services and the quashing of workers’ rights and environmental protections, all to swell the coffers of the Koch brothers.

12. “We voted out”

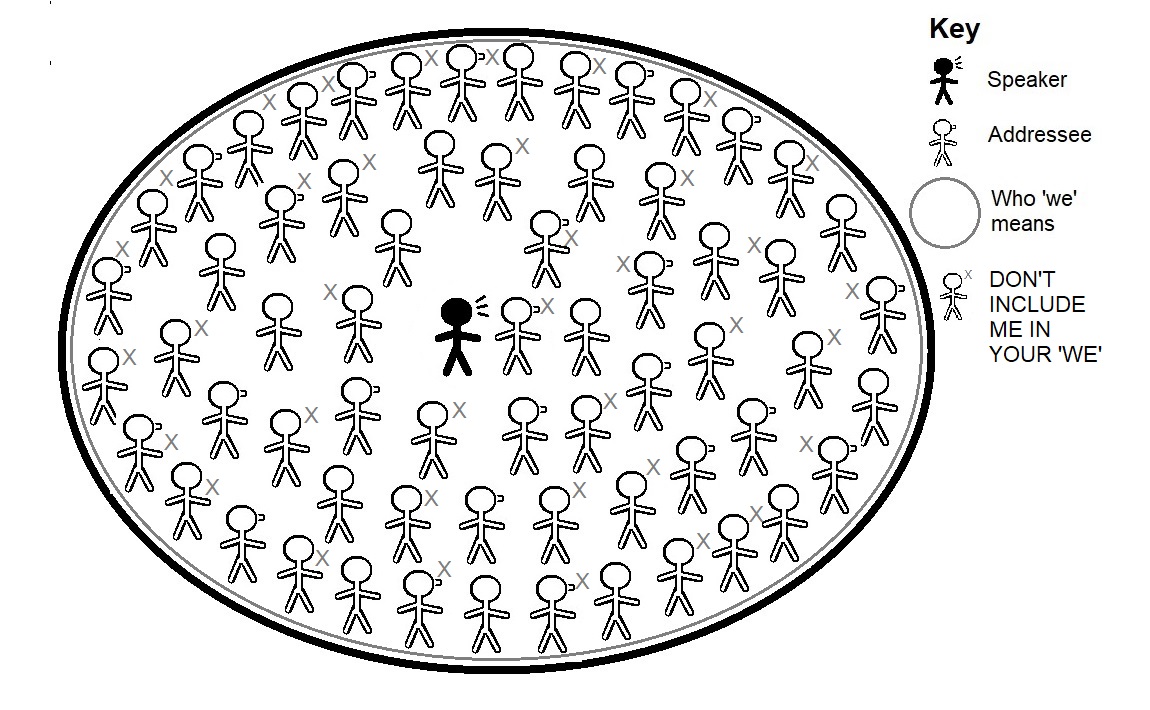

An intimidatory “we” similar to No 10, and a favoured tool of the Brexit voter. There’s a huge and important disjunction here between who the speaker intends us to picture, and who they actually mean. In this case, the intent is to give the impression that the United Kingdom voted as one unit to leave the European Union, when in reality, only 17.4 million people, or 26% of the population, did.

An intimidatory “we” similar to No 10, and a favoured tool of the Brexit voter. There’s a huge and important disjunction here between who the speaker intends us to picture, and who they actually mean. In this case, the intent is to give the impression that the United Kingdom voted as one unit to leave the European Union, when in reality, only 17.4 million people, or 26% of the population, did.

Just under a quarter of the population voted for the exact opposite outcome, and the remaining half voted for nothing at all (which you could legitimately interpret as a passive vote for the status quo). Furthermore, 3 million EU citizens and a sizeable number of the 1.5 million British migrants to the EU were denied a voice.

(The phrase “the people” is often used in the same misleading fashion: “the will of the people”, “the people have spoken”, “enemies of the people”.)

But this “we” falls apart at the slightest scrutiny. As long as your collective aims are nice and broad and vague, you can muster quite a lot of “us” in support of them. But as soon as you try to narrow down those aims to specific course of action, the illusion of unity vanishes and your following splinters – as we are now seeing with the various warring Brexit factions.

“What do we want?”

“Change!”

“When do we want it?”

“Now!”

“What specific changes do we want to make?”

“Well, Parvinder favours option A. Sally prefers option B, which is completely incompatible with option A, and Keith doesn’t really have any ideas. He’s just cranky.”

13. “Let’s take back control”

The “we” is rather buried, in the form of that apostrophe+s, in Vote Leave’s ingenious and probably decisive slogan for the 2016 referendum campaign, but it’s crucial.

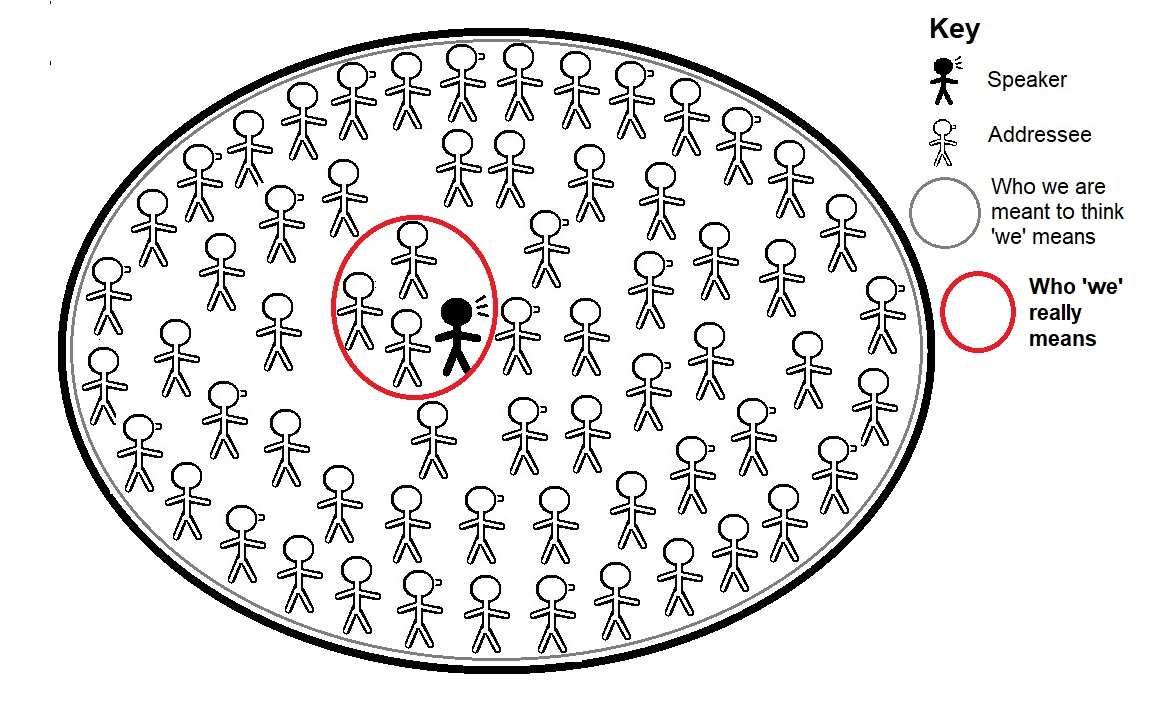

Almost three years after the vote, no Brexit campaigner has yet been able to explain how leaving the EU will restore any control to the average person in the street. The truth is, the only beneficiaries of the change will be whoever is in power at Westminster and, some way down the line, the big businesses that lobby them.

And they will benefit precisely at the expense of the average person in the street, whose rights and protections they will be free to curtail once the UK leaves the European Union. The slogan is a ruthlessly cynical exploitation of the ambiguity of the word “we”. It implies everyone in the UK; in fact it means only a very small subset of that group.

Dominic Cummings and his fellow cacodemons were essentially trying to pull the same trick as your GP – but with far less benevolent intent. In return for nothing more than putting a cross in a box, they seemed to promise, you could become part of a project, a team, a family. You’ll feel valued again! And that family will go on to achieve untold glories, that you can share in!

Alas, the bitter truth for Brexiters is the same as for the football fan: while you may experience the elation of vicarious victory, it’ll cost you a small fortune, and you won’t so much as lay a finger on that trophy.

Cummings, Johnson, Rees-Mogg, Westley et al can say “we” till they’re blue in the face – but know this: you, the common person, are not and never will be part of their club.