The art of the smear: how the far right destroyed public discourse

Online debates these days unfold with all the dignity and decorum of a stag do at a Reading Wetherspoons

“Whoever first hurled an insult at his enemy instead of a spear was the founder of civilization” – Sigmund Freud

Insults are nothing new. From the 4th century BC ding-dong between Demosthenes and Aeschines, to Shakespeare’s “You starveling, you elf-skin, you dried neat’s-tongue, you bull’s-pizzle, you stock-fish!”, to Noel Gallagher’s laceration of Robbie Williams as “the fat dancer from Take That”, incivility is as old as civilisation. We start calling each other names in the playground and, if the Leave voters I’ve encountered online are any guide, there’s no upper age limit on abuse.

But suddenly, it’s Ragnarök out there. Get involved in an online discussion about anything from topiary to the Tweenies and the chances are you’ll be set upon within minutes. Political “attack ads” were once frowned upon; now they’re the norm. There’s hardly been a single positive message in the UK general election campaign thus far; it’s just been smear after slur after slight. Most modern debates – usually online, but increasingly in real life – unfold with all the dignity and decorum of a stag do in a Reading Wetherspoons.

It’s all rather odd, because as I’m sure you already know, attacking a person in this way, instead of the substance of what they’re saying (or in the case of political debate, their policies), is a fallacy: a failure of reasoning that renders a claim invalid. In this case – the argumentum ad hominem fallacy – abuse is invalid because the truth of a person’s statement has nothing to do with their character, past behaviour or friends. Just because it’s Tony Blair saying, “Two plus two equals four”, that doesn’t mean the real answer is five. Much as it pains me to quote Margaret Thatcher, on this point, she had it right: “If they attack one personally, it means they have not a single political argument left.”

Civilisation is supposed to be advancing. We are devising ever better theories to explain the world, sending more kids to university, sharing more information, faster, than ever before. The use of logical fallacies should be declining, not increasing.

So why the recent explosion of invective? Some blame the global climate of fear since 9/11 and the ensuing jihadi atrocities. Some say it’s deindividuation: when we’re online, or part of a large group, we enjoy anonymity; our actions have fewer repercussions for us, either because we are untraceable, or we because we share responsibility with others. When we are at one remove from the consequences, our actions tend to be less inhibited.

Others point to the bubble effect, the fact that people tend to assort themselves into groups of like-minded people. If we spend too long in these echo chambers, hearing only what we want to hear, then we are likely to react more aggressively when someone attacks them.

These theories all have merit, but I don’t believe they are enough to explain the extent of the poisoning of discourse, or the speed with which it’s happened. Echo chambers have always been with us – we’re a tribal species – and abuse is less effective online than in the real world, because while we may be anonymous, our opponents often are too, so we don’t have as much informational ammunition.

There’s something else going on. I have a theory of my own, but before we go into that, it would be helpful to look at abuse in more detail. First, a key distinction. There are two broad classes of ad hominem, which serve different purposes. The first is relatively innocuous and is largely accepted as a legitimate debating tactic.

“You, sir, are drunk.” “And you, madam, are ugly … but at least I shall be sober in the morning.”

Winston Churchill’s zinger to Lady Astor is a regular chart-topper on “Top 10 Putdowns” lists – but like all ad hominems, it’s a fallacy. From a purely logical perspective, Lady Astor is in the right. Churchill’s comeback is fallacious; as well as being offensive, it’s irrelevant. He’s also drawn a false equivalence. While he is quite capable of controlling his level of inebriation, poor Lady Astor has no such dominion over the shape of her face.

But if Astor wins on substance, Churchill wins on style. This is a class of ad hominem that you might call a joust. It’s usually found in the context of the cut and thrust of repartee, and its purpose is to throw the opponent off balance. If your interlocutor has the upper hand in a discussion, a droll, well-targeted personal attack can move the debate to surer ground. Since people’s natural reaction to being attacked is to defend themselves, they’ll often attempt to defend the slight instead of driving home their advantage.

Jousts take place in real life, in real time, in the real world. If they hit the mark, they earn kudos for the wielder. Churchill’s comment may have been mean, but it was quick, it was (presumably at least partially) accurate, and it took some courage – presumably Dutch – because the target of his tongue-lashing was standing right next to him. Above all, it was funny.

Many of the greatest literary minds in history have been able practitioners of the joust. Chaucer, Swift, Pope, Voltaire, Johnson, Twain, Byron (“Posterity will ne’er survey/A nobler grave than this:/Here lie the bones of Castlereagh:/Stop, traveller, and piss”), Wodehouse (“She’s got brains enough for two, which is the exact quantity the girl who marries you will need”), Wilde (“I never saw anybody take so long to dress, and with such little result”) and Orwell (“He is simply a hole in the air”) all earned their stripes partly by tearing others off a strip. We excuse these slights, applaud them even, because they show qualities that we aspire to: intelligence, originality, speed of thought. Besides, there’s often a sense that the target had it coming. Who are you going to side with – the guy who won the second world war, or some judgmental fuddy-duddy?

The second class of ad hominem is the smear. It too is rapidly becoming an ingrained part of public discourse, but it is, I will try to argue, far more dangerous, and has no place there. Smears come in four main varieties.

1) Character assassination

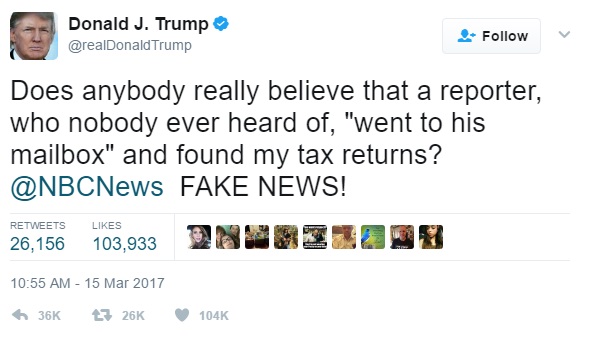

There’s really only one contender for the title of World’s Bigliest Trash-Talker. As of March 2017, Donald John Trump was estimated to have slagged off no fewer than 320 different people, organisations and … items of furniture. Yeah, he dissed a table.

Trump’s gibes have the same drawback as jousts – they’re irrelevant to the discussion – and none of the merits. They’re not funny. They’re inane, unoriginal, and, as often as not, false. They do not signal a quick wit, because for the most part Trump delivers them via Twitter, or in prepared speeches to adoring crowds. And they are anything but brave, because Trump’s opponents are rarely in the same room when he vilifies them. To compare the US president’s infantile taunts to Shakespeare’s eloquent excoriations is to stick a Lego staircase next to the Taj Mahal.

And yet here he is, signing poorly drafted executive orders like baseball cards, merrily topping up the swamp with the contents of every septic tank in America, and hooking his drives ever closer to the nuclear bunker. How so?

When you look at the Mango Mussolini’s modus operandi, all becomes clear. Shower your enemies with insults; see which gains the most traction (ie likes and retweets); then use it again and again, until it becomes irretrievably associated with the target. So Hillary Clinton becomes “Crooked Hillary” at every mention; the New York Times “the failing NYT”; and rival for the Republican nomination Ted Cruz “Lyin’ Ted”.

These remarks are not designed to artfully throw Trump’s opponents off balance or to enhance his comic credentials. They’re not really directed at his opponents at all; they’re aimed at the wider world. Trump is not trying to undermine what his rivals are saying now, but everything they have ever said. These are cynical, systematic smear campaigns. And incredibly, through sheer force of repetition, they worked.

Most people are smart enough to realise that, just because a hay clump stapled to an overripe satsuma repeats something over and over again, that doesn’t mean it’s true. Unfortunately, it seems there are just enough credulous idiots out there for Trump’s bullying tactics to pay off. By means of a million gutless, leaden, charmless, bogus backstabs, Trump managed to destroy the credibility of everyone who stood in his way.

TL;DR: Your argument is rubbish because you are rubbish.

2) Tu quoque

“L’hypocrisie est un hommage que le vice rend a la vertu.” – François VI, Duc de La Rochefoucauld

The tu quoque – Latin for “you also” – is a special case of ad hominem also known as the appeal to hypocrisy. Here, instead of trying to undermine the target’s argument by maligning their character, you are attempting to do so by pointing out things they have said or done in the past that contradict their current position.

A tu quoque often feels somehow more cutting than a basic ad hominem, because, well, no one likes a hypocrite. However, it is just as invalid as a criticism, because it too fails to disprove the premise. Whether your past or current actions are 100% consistent with your view or not is completely immaterial. Let’s take a recent example.

We live in a world where personal and public interests do not always align. (This is why we need governments; to balance private freedoms against the general good.) Politicians aren’t just politicians. They are also, despite appearances, human beings, and many of them are parents.

When you’ve got your MP’s hat on, grammar schools are a bad thing. Most studies have concluded that while they might benefit the few who attend them, they have a deleterious effect on other schools; they suck in all the best pupils and the best teachers, and regular schools suffer as a result.

But now look at the question from the viewpoint of the MP as parent. Grammar schools exist. The kids who go there do better. Given the choice between sending them to a grammar or to a comprehensive, which way do you swing? The effect of your decision on other people is infinitesimal – but it could make a huge difference to your child. You’re technically a hypocrite if you choose the grammar, but it doesn’t mean your opposition to the principle of grammars is wrong.

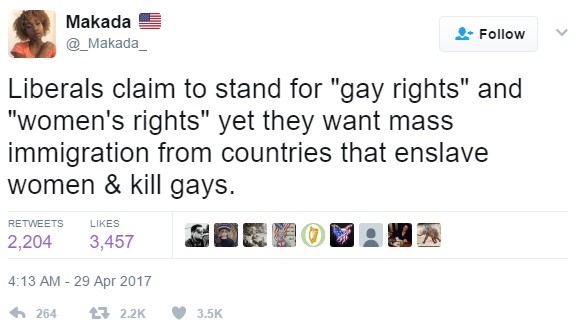

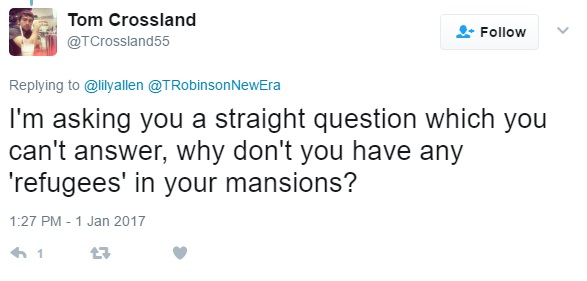

When Lily Allen and Gary Lineker spoke out in defence of refugees last year, they were bombarded with incandescent messages along the lines of “Well, how many are you taking into your mansion?”

Like May’s tirade, the detractors were missing the point. It isn’t Lily Allen’s job to look after refugees. There are lots of childless couples who’d probably be more than happy to take in a Syrian orphan, for example. The alt-right are constantly frothing at the mouth about the atrocities committed by Isis – but how many of them are donning combat fatigues and heading off to the Levant? If Allen and Lineker are hypocrites, so are they.

Few of us have the time, the equipment or the expertise to devote our lives to solving all the world’s problems. There are others better placed to tackle these matters: police, governments, charities. All we can do is flag them up, perhaps donate some cash, or if we’re lucky enough to have a free weekend, organise a trip to Calais to hand out clothes and food.

The fact is, we’re all hypocrites on a regular basis. Have you ever sat in gridlock and moaned about the traffic? You’re part of the problem! Ever merrily sucked on a fag while gravely warning a young relative never to take up the habit? Pot, meet kettle! Worried about overpopulation – and you have two kids? You’re a fine one to talk!

TL;DR: Your argument is rubbish because not every single thing you have ever said and done in your entire life has been 100% consistent with it.

3) Circumstantial ad hominem

The implication that a person has taken a position purely because it suits their agenda; they cannot be trusted on a particular issue because they have a horse in the race, or their judgment is otherwise clouded.

There’s sometimes something to this one. Most prisoners on death row insist that they are innocent, because it’s hugely to their advantage for others to believe them. However, by strict logical criteria, their claim is not automatically untrue simply because it is in their interest. We just need to take it with a healthy pinch of salt.

TL;DR: Your argument is rubbish because you are biased.

4) Guilt by association

Fetch the Nurofen. We are now entering the realms of spectacularly twisted logic, where the cognitive gymnastics can induce migraines in the unprepared.

4) is essentially 3) on steroids. The association fallacy is the most egregious and toxic of ad hominems, since it attempts to invalidate someone’s point by smearing them on the basis of her membership of, or tenuous association with, a particular group.

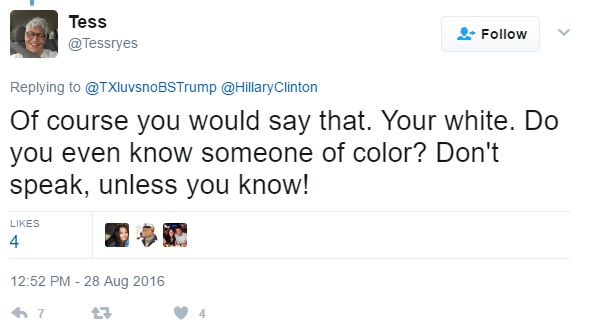

It’s become depressingly common practice, in online discussions, for your opponent to try to dig up dirt on you. They’ll read your profile, scan your previous tweets or comments, even Google you in their quest for incriminating evidence. Failing that, they’ll use whatever they find to try to pigeonhole you.

Why? Because then they can write off your opinion on the basis that they have already written off the opinions of everyone in your group. “Aha, you live in London! Of course you’d parrot pro-EU propaganda – membership benefits the metropolitan elite!” (Forty per cent of Londoners voted Leave.)

As well as committing the same logical misstep as the other smears – implying that a person’s identity is somehow relevant to their point – the association fallacy asks us to accept two further false propositions: a) that the entire group’s views and values are without merit; and b) that everyone in that group thinks and acts in exactly the same way.

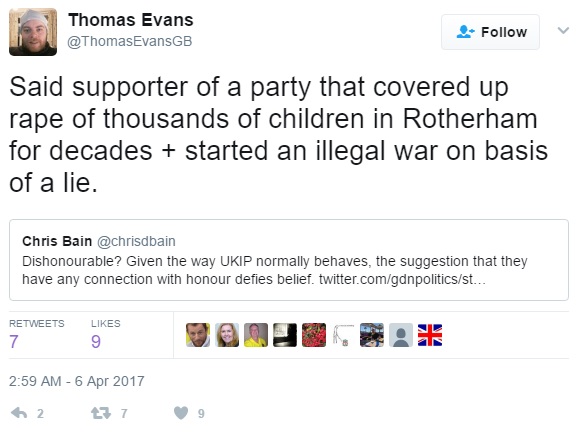

Loath as I am to cut the hate-fuelled shitrag that is the Daily Mail any sort of slack, the continued attacks over its historic sympathy for Hitler and the Blackshirts make no sense. For one thing, everyone involved with the paper in 1934 is dead. New office, new owner, new staff. The words “the Daily Mail” now refer to a different entity; there is no immortal “Daily Mail soul” that inhabits everyone who sets foot in its offices. (True, the current team is starting to look more and more like its historic incarnation, but from a logical standpoint, there is no reason why this should be so.)

The guilt by association fallacy effectively means that no one can ever be right, because it holds that your view is worthless if you, or any group you have ever been associated with, have ever done anything wrong.

Telltale phrases: “Typical Leaver”, “You liberals are all the same”, “Just what I’d expect from a Muslim”.

TL;DR: your argument is rubbish because I consider (erroneously) that everyone in the group I have assigned you to (erroneously) is wrong about everything.

I used to think that humanity was slowly waking up to the preposterousness of generalisations like “All men are bastards”, “All Jews are stingy” and “All Gypsies are thieves”. But suddenly, writing off entire cross-sections of society at a stroke is enjoying a renaissance.

I picked the Daily Mail example for a reason. Of all the smear campaigns mounted in the last few years, one of the most sustained and successful has been the coordinated effort to discredit the entirety of the world’s journalists – or, to use the dismissive alt-right term, the “MSM” (mainstream media).

Organisations like the Mail, Express and Fox News haven’t helped the cause with their rabidly partisan headlines and editorials, and it’s true that the Independent, for example, has a strongly pro-EU slant. But the far right demagogues would have you believe that every journalist in every media outlet in the world is part of some huge conspiracy to deceive you, to keep a boot on the throat of the working classes and maintain the status quo.

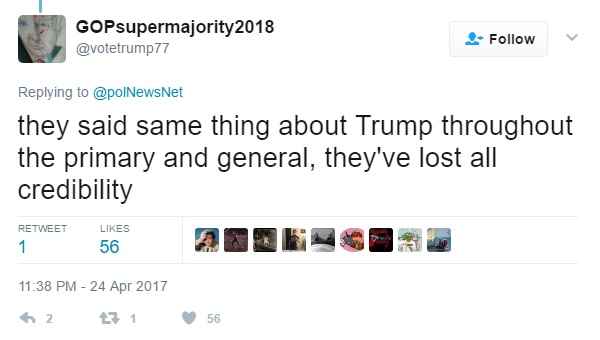

The alt-right pursue this narrative by seizing on any and every mistake, oversight or lapse of judgment from any publication or broadcaster and magnifying it to ludicrous proportions. So, because the Guardian once ran an erroneous story about Jeremy Corbyn sitting on the floor of a train, we now cannot believe any Guardian story we read. Because Buzzfeed runs listicles and fluff pieces on its site, its investigative journalism is worthless. Because the BBC once published a news item about the negative effects of Brexit, it is irredeemably biased in all matters. The fact that Nigel Farage – an MEP for a party with no representation in parliament who only bothers turning up for work to sour the UK’s foreign relations – gets more airtime than any other politician in the UK is neither here nor there.

Yes, the mainstream media have made mistakes. And yes, some lean in a particular political direction. But on the whole, they try to give a reasonably balanced view of things. They are bound by ethical standards and libel laws, and subject to the oversight of a regulator. When they get things wrong, they apologise, they retract, and they print corrections.

Again, most people don’t buy into the alt-right’s absurd narrative. But a small, significant section of society have swallowed the lie, and now routinely reject any facts from mainstream sources as “biased” or “fake news”. To them, all of the media – from the Independent to the Guardian to the Mail to the BBC to ITV to CNN to the Times to Al-Jazeera to Buzzfeed to the South China Morning Post to the Dumfries & Galloway Standard – are all part of some vast conspiracy to prop up the metropolitan elite. We have now reached a point where a Brexiter, in a discussion about Brexit, will demand that you provide evidence to back up your point – and then, when you do, airily dismiss it because it happened to be published in the Sunday Times.

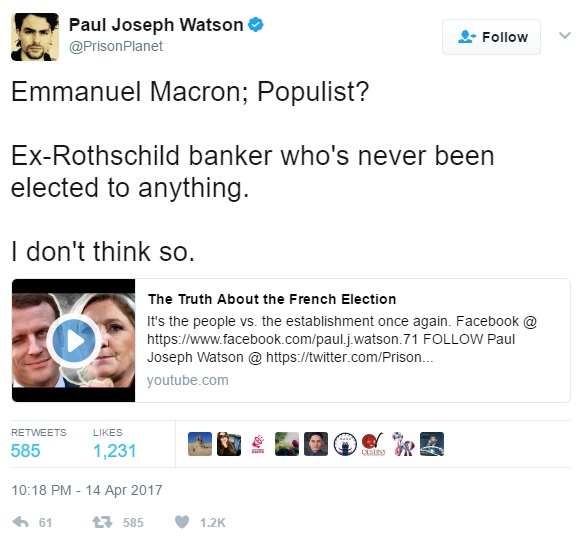

So if no conventional news sources can be trusted, who are these people listening to? Who has stepped into the information vacuum to expose The Real Truth? Blow me down with a feather, if it isn’t those selfsame alt-right demagogues! The alt-right demagogues, whose newsgathering resources generally stretch to a Twitter and YouTube account and a camcorder in their mum’s basement. The roving-reporter alt-right demagogues, like Paul Joseph Watson, who openly admits that he hardly ever leaves his Battersea flat, Julian Assange, who has been trapped in the Ecuadorian embassy for five years, and Katie Hopkins, who broke her world exclusive that there were quite a few Asian shops in London by going to the shops.

(This post is plenty long enough without a diversion into the shameless mendacity of the alt-right, but I’ve posted a few examples here, and there are plenty more at Snopes, FactCheck.org and FullFact.)

It wasn’t enough, of course, to smear the media. They are, after all, just mirrors to majority opinion. If a new order is to be imposed, all the traditional institutions must be undermined.

Dominic Cummings’ “Take back control” was very clever. The NHS promise on the bus probably did it for some people. The Breaking Point poster, even though immigration from outside Europe had precisely jack shit to do with the EU, undoubtedly won over a few racists. But for me, the real stroke of genius from the Leave contingent, and the turning point of the whole campaign, was Michael Gove’s “People have had enough of experts.”

Never mind that he was told to say that by one of the exact same metropolitan elite experts he was maligning. Never mind that he apologised abjectly for the comment the next day and retracted it altogether months later. In one pithy phrase, Gove manage to articulate the fury of millions of underachievers. He also single-handedly destroyed the last scrap of trust the public had in the system. Suddenly, the opinion of the man in the street was just as valid as that of someone who had spent years mastering her subject.

Gove’s (or, rather, Cummings’) ludicrous argument, that, because some trusted individuals once made an incorrect prediction, all their predictions are worthless, was the final justification for a Brexit vote among a decisive group of waverers. This arrant nonsense, combined with parallel whispering campaigns – Boris Johnson merrily defaming the EU in his columns for the Telegraph and Spectator, and the relentless demonisation of immigrants and Muslims in the Express, Mail, and far-right “news” sites – was what dragged Leave over the line.

For years, liberals ignored all this mudslinging, I guess because they assumed no one was gullible enough to believe it. Hopefully, they’re waking up to the fact that they can’t afford to ignore it any more.

(I’ve got more to say on this subject, but I’ve already wittered on for too long. Part two will follow shortly.)

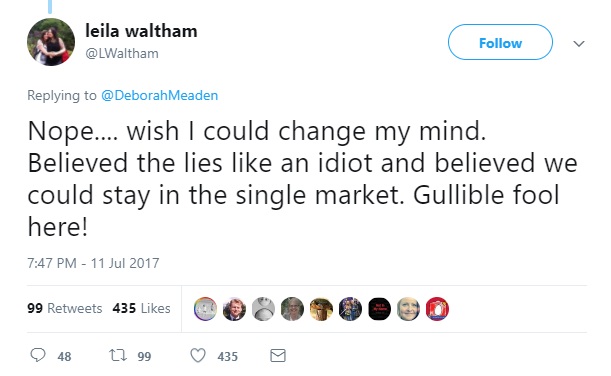

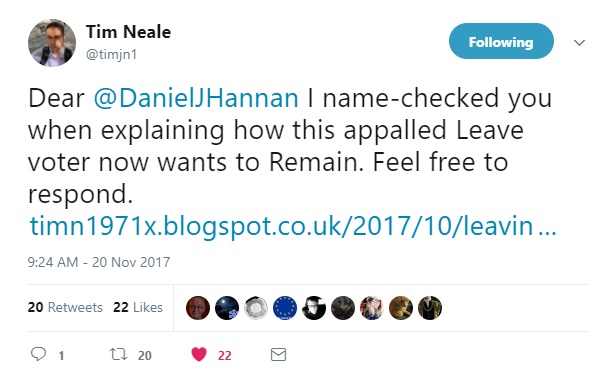

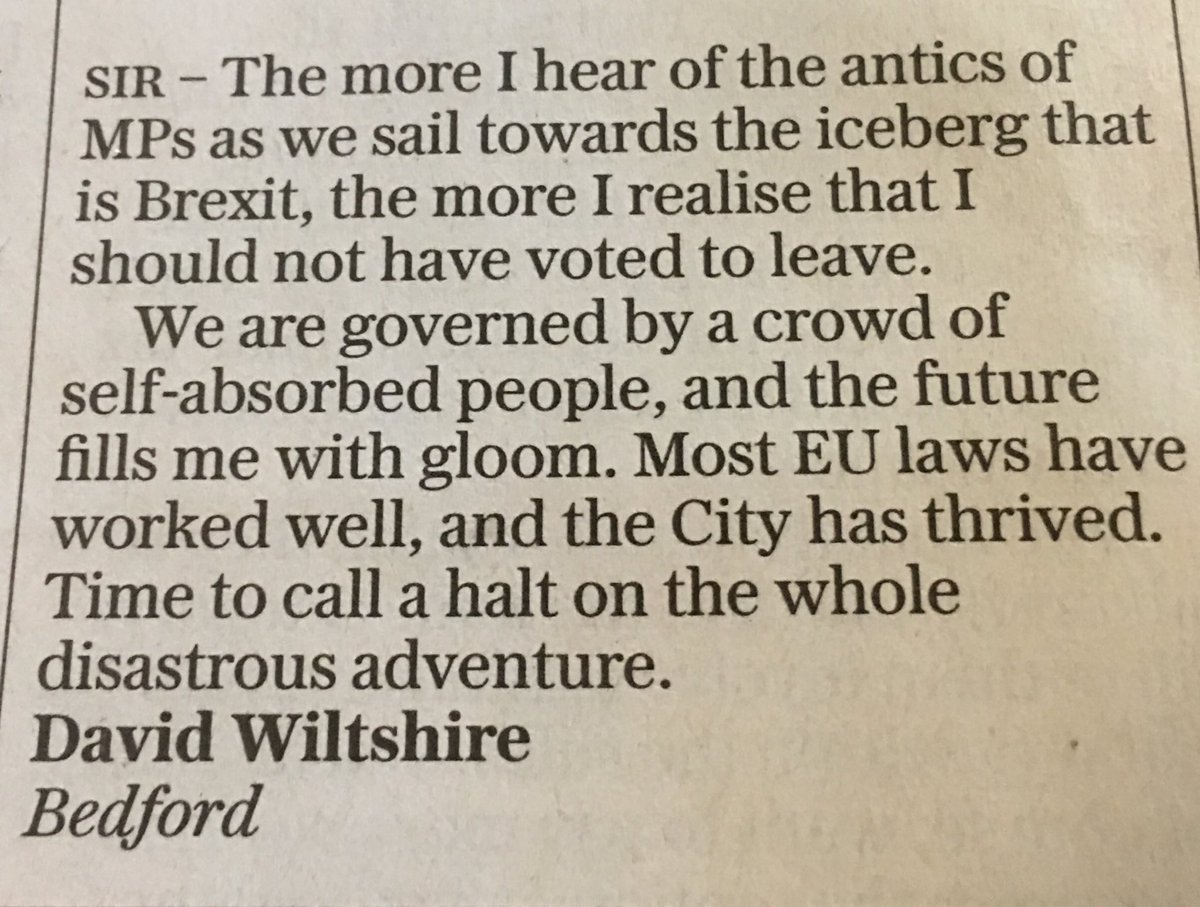

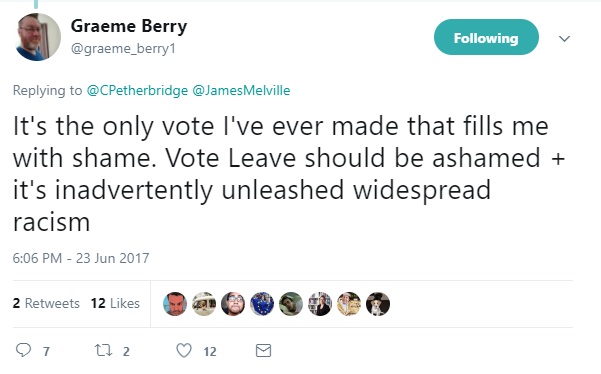

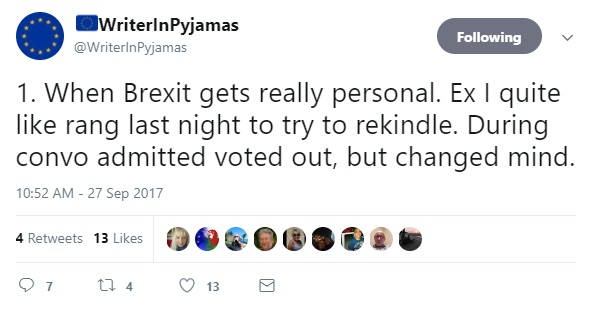

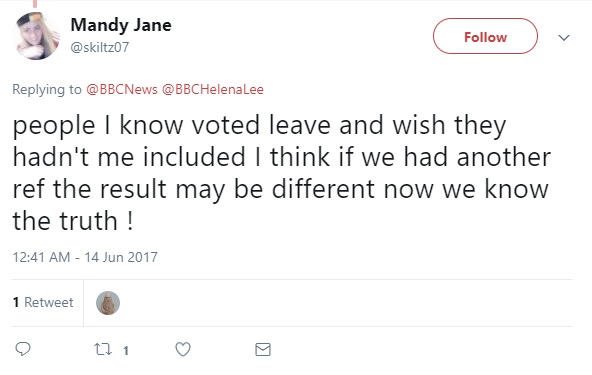

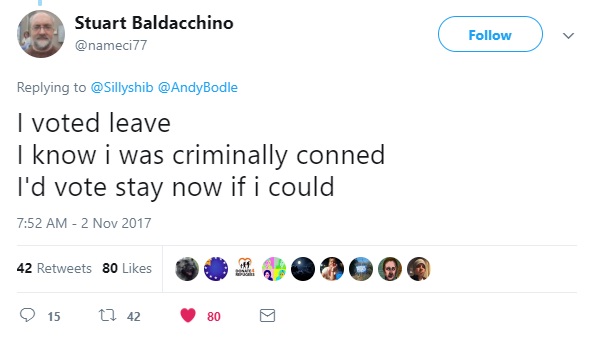

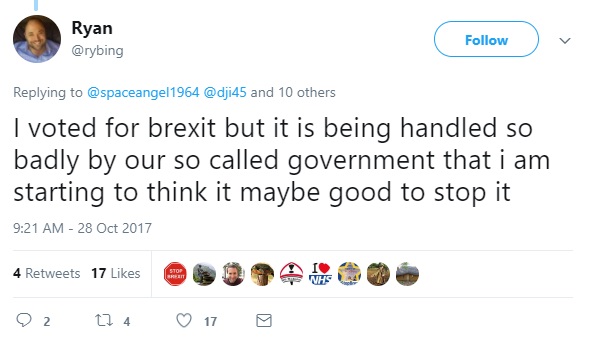

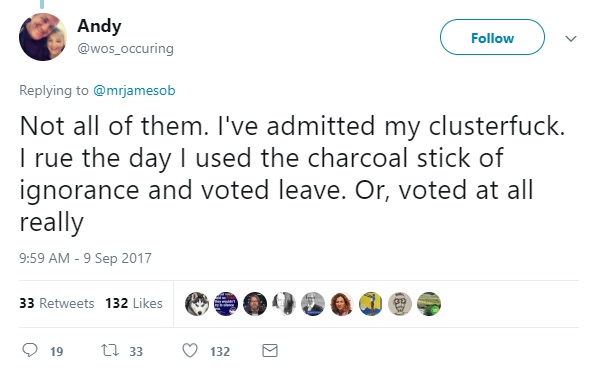

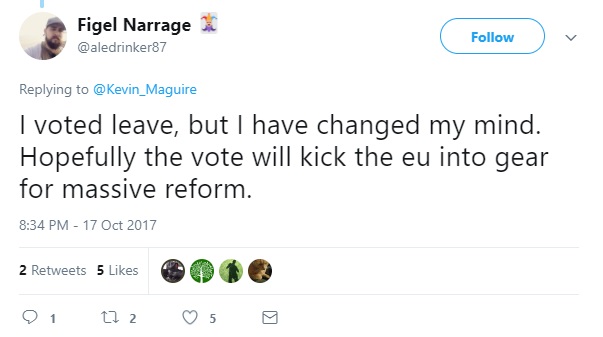

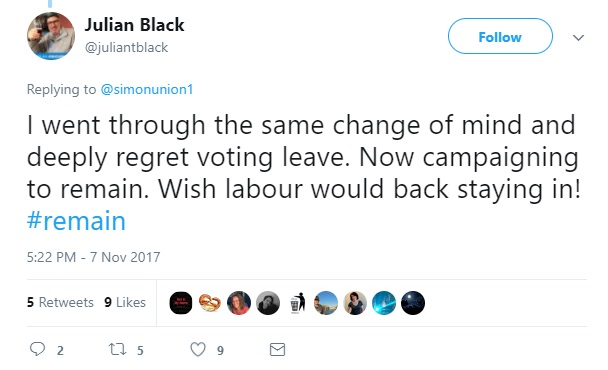

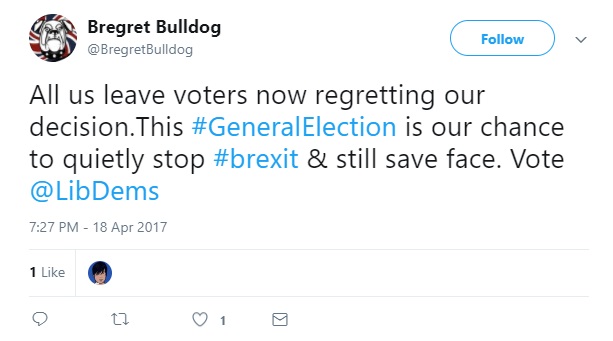

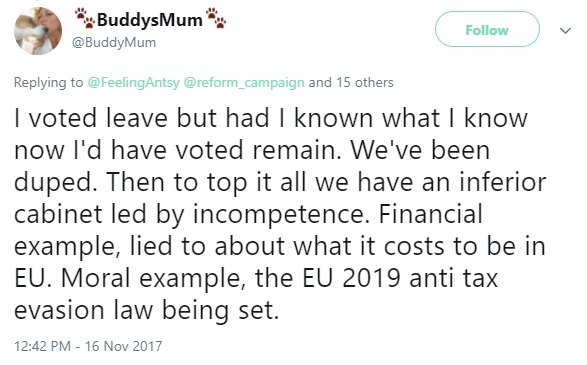

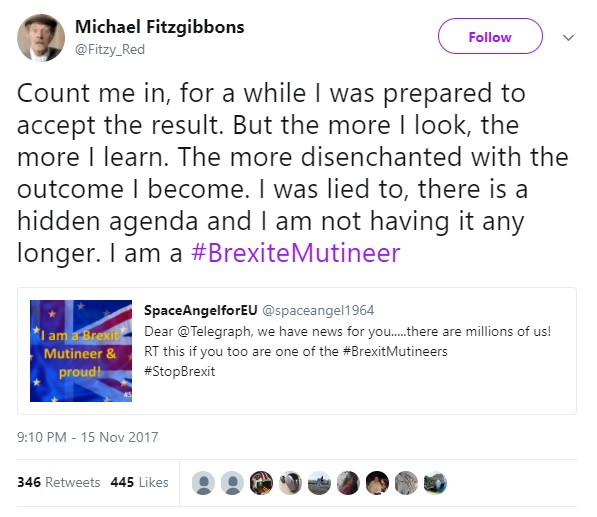

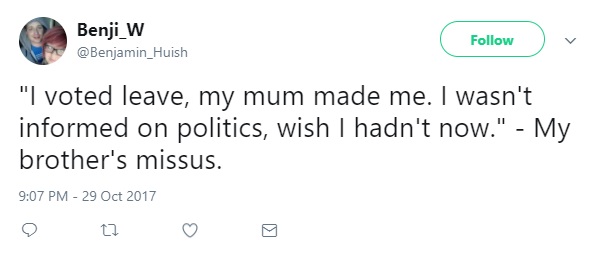

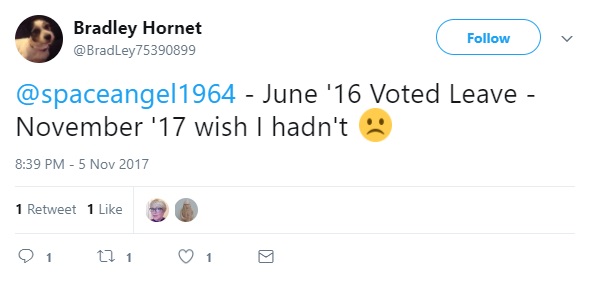

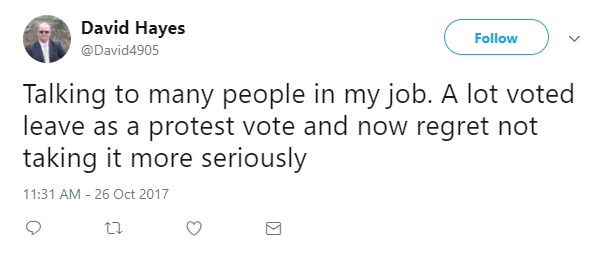

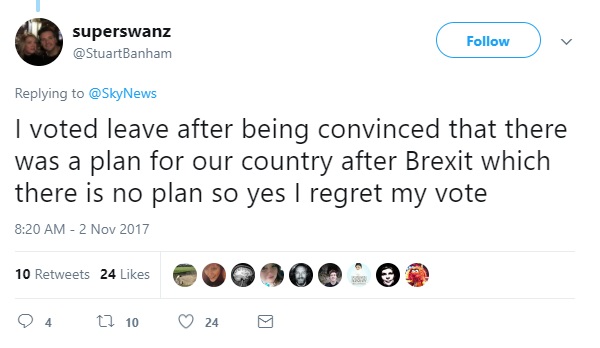

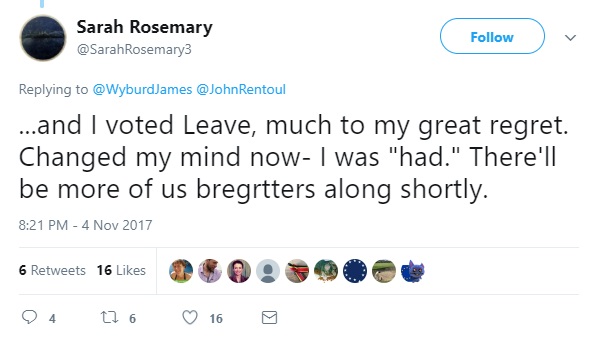

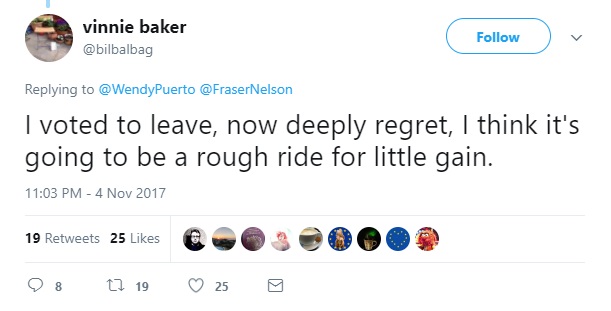

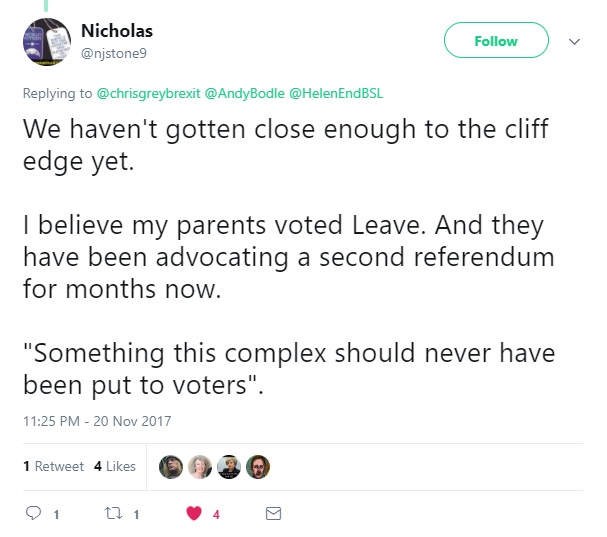

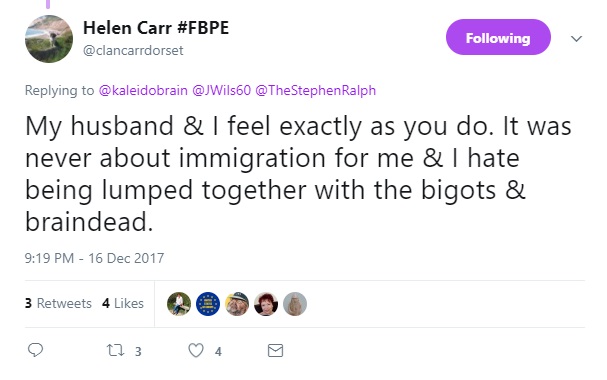

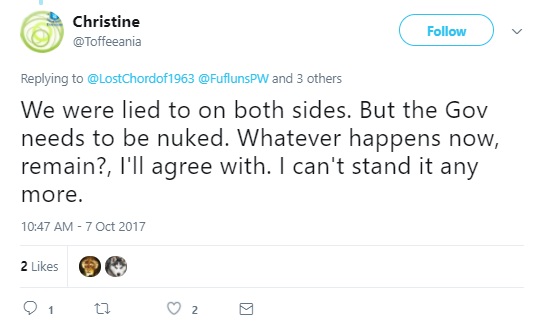

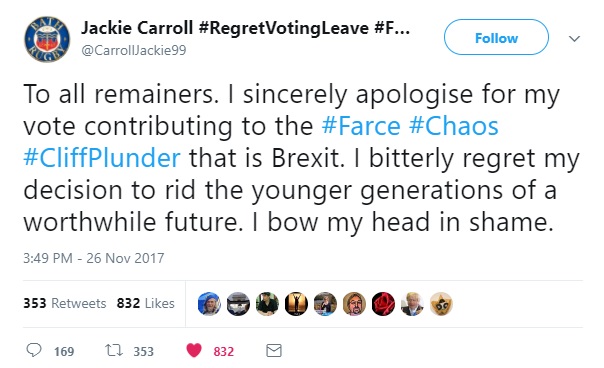

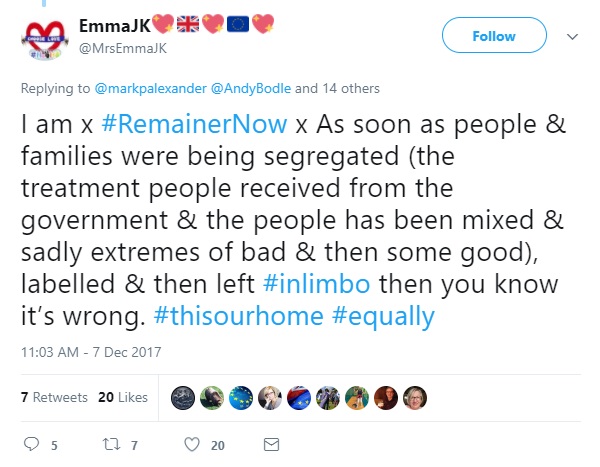

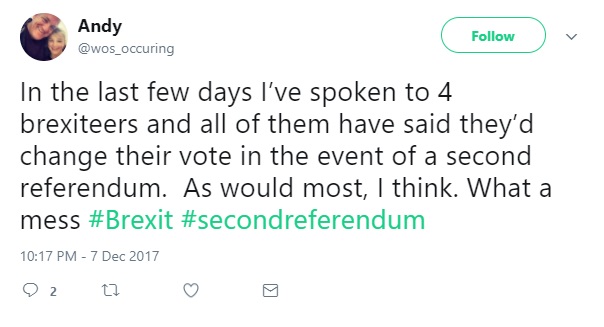

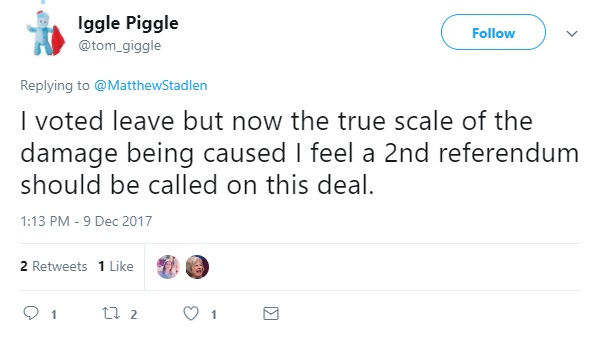

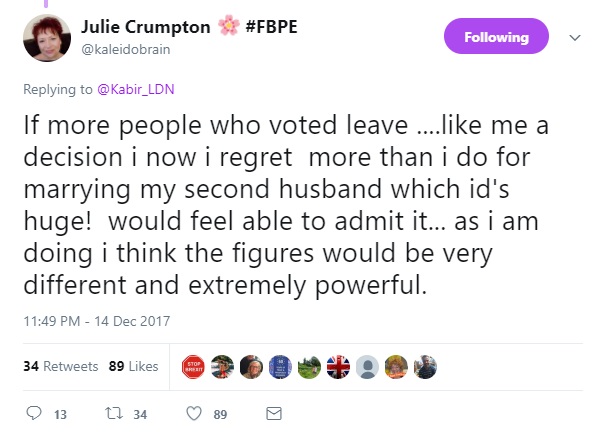

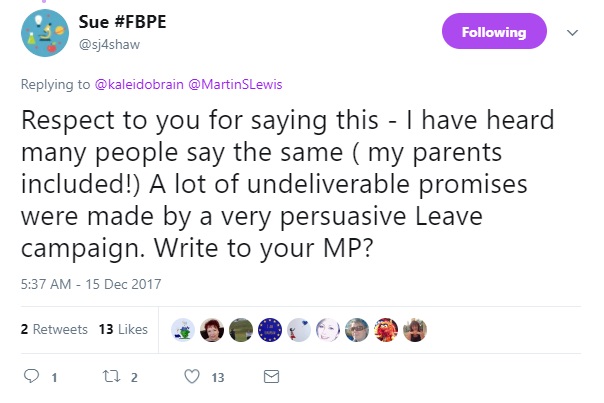

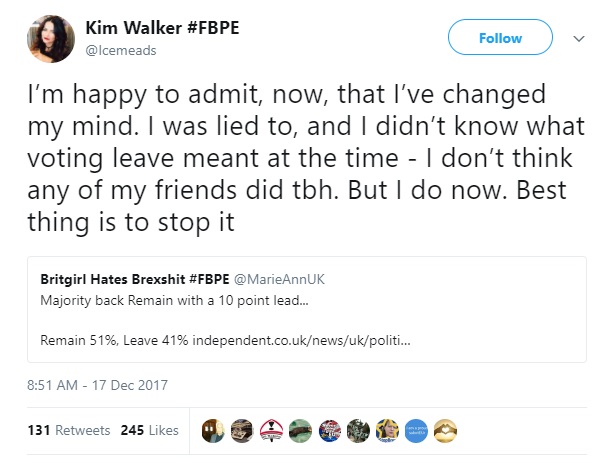

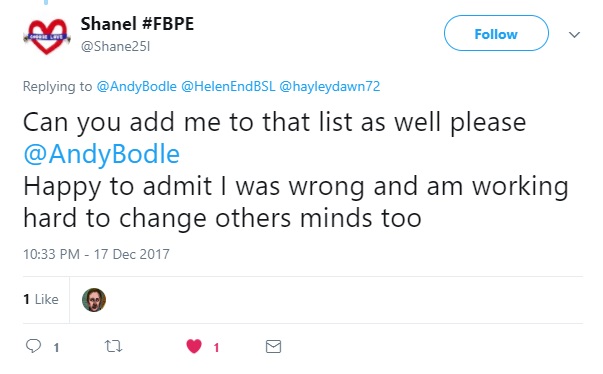

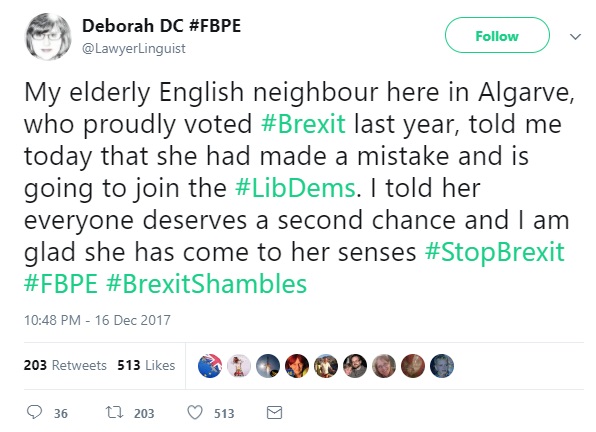

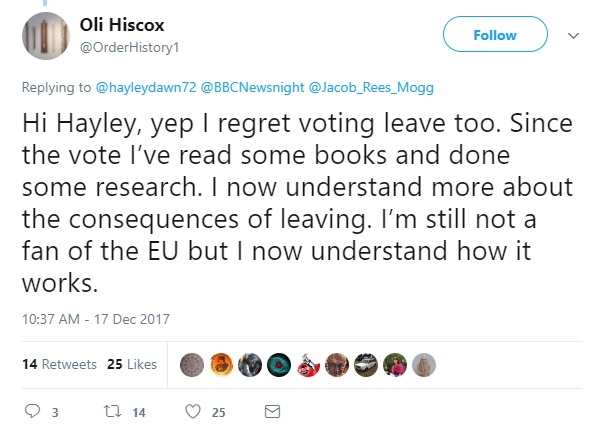

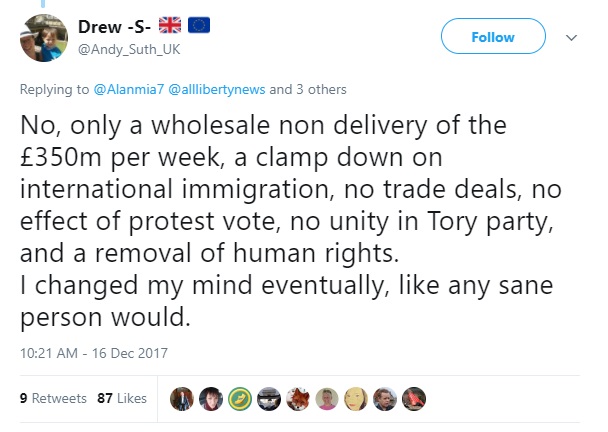

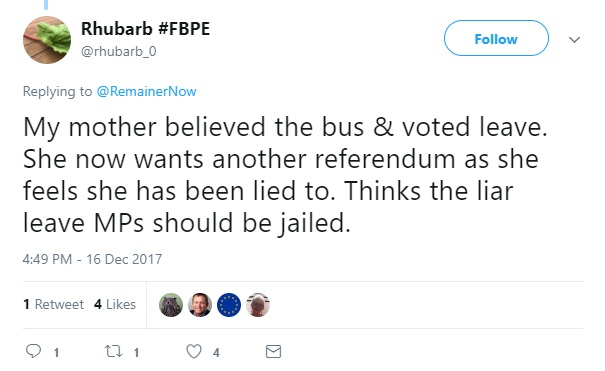

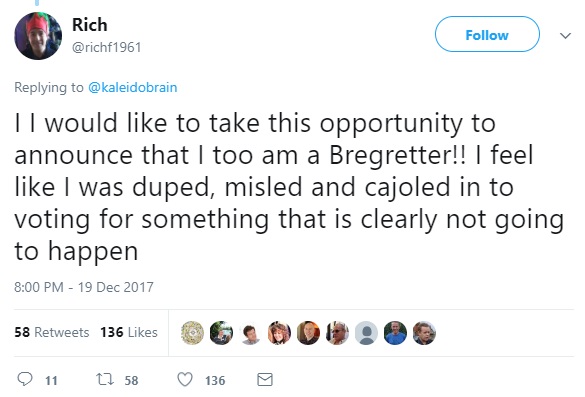

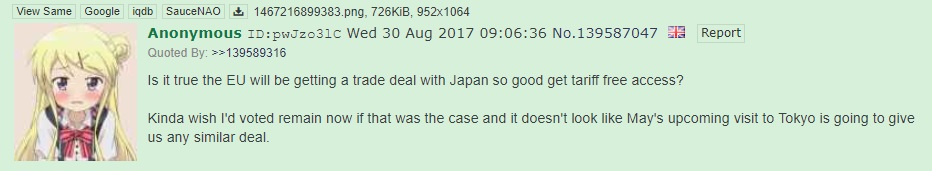

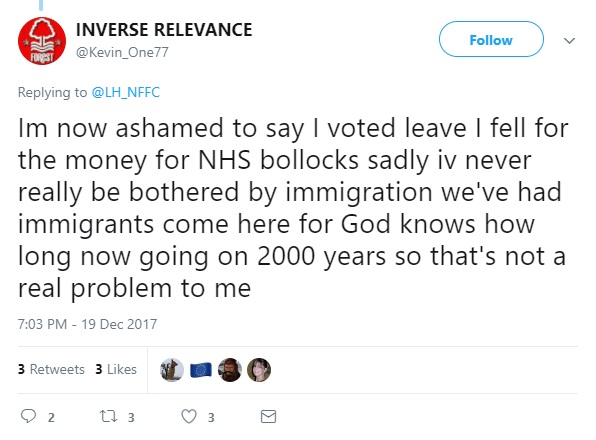

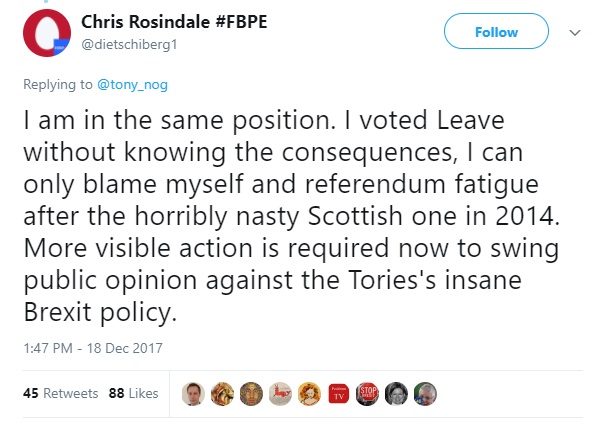

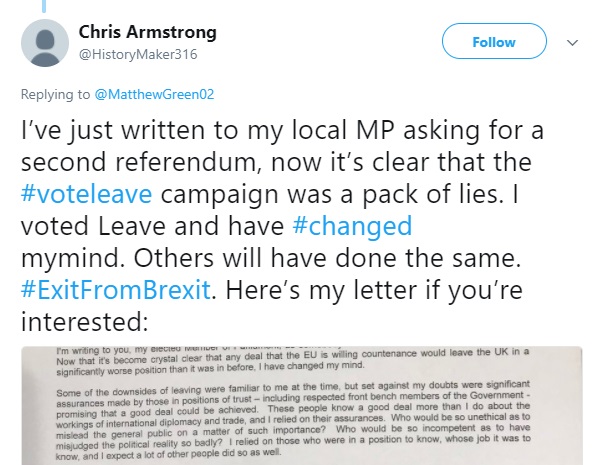

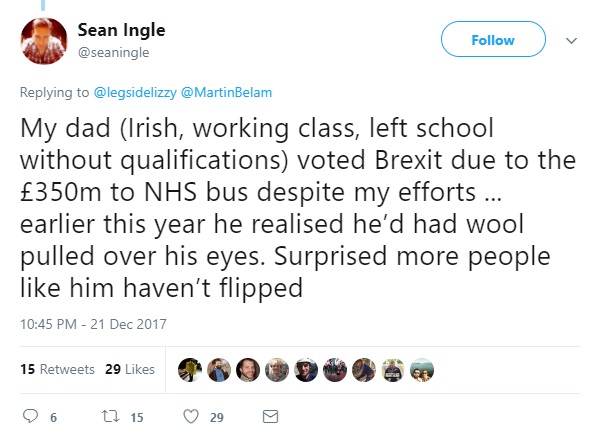

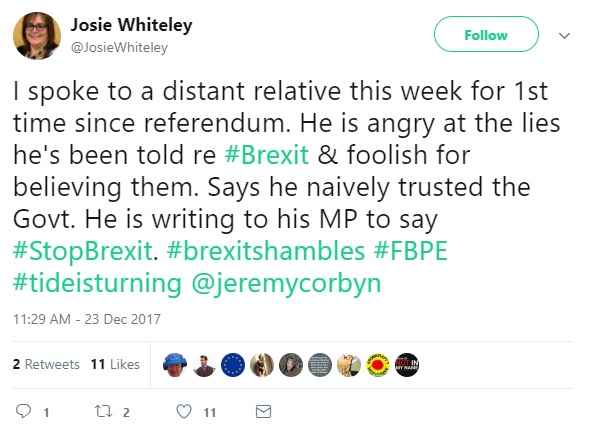

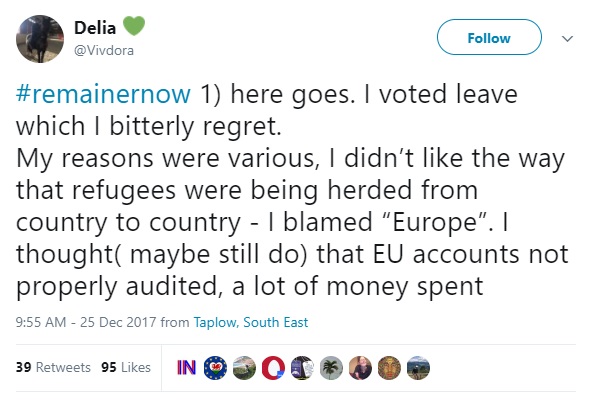

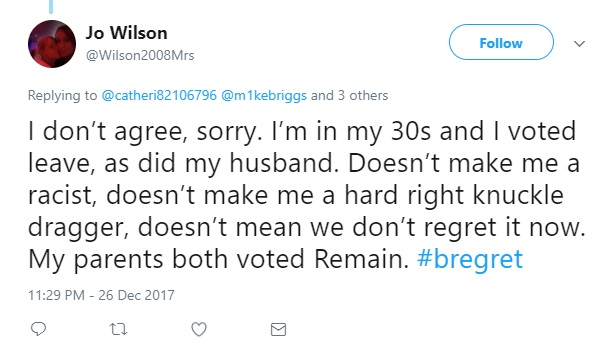

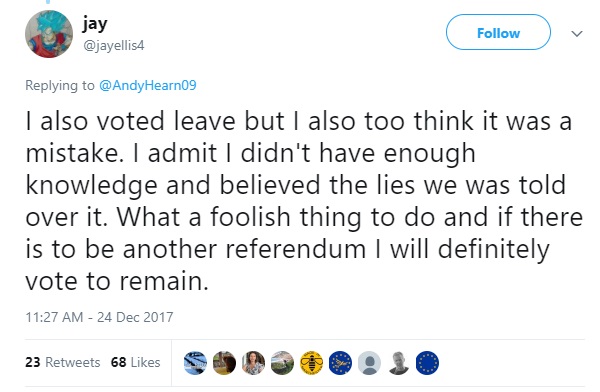

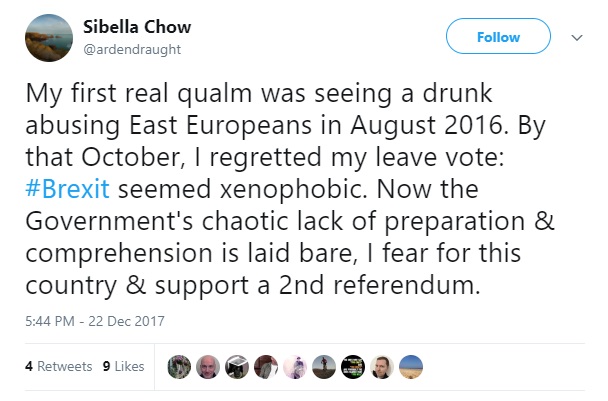

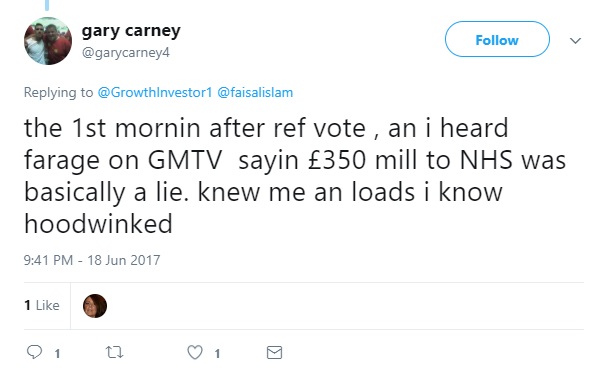

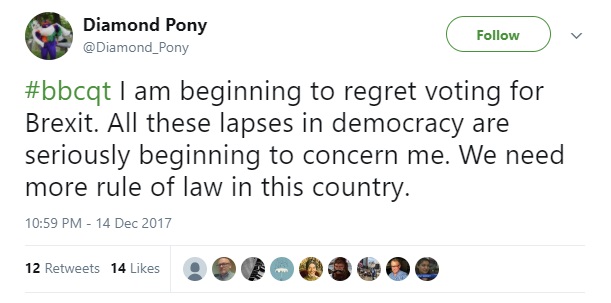

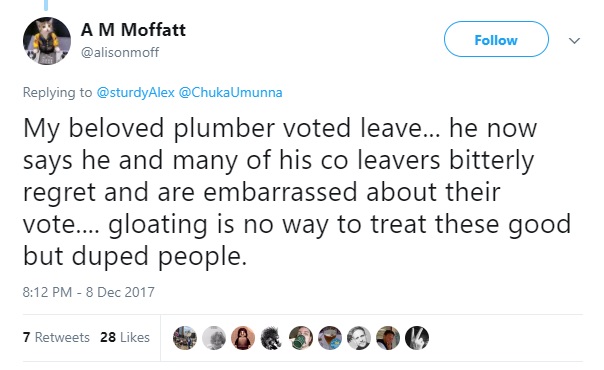

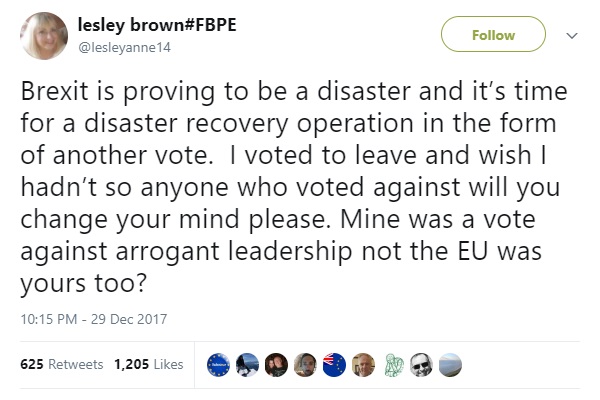

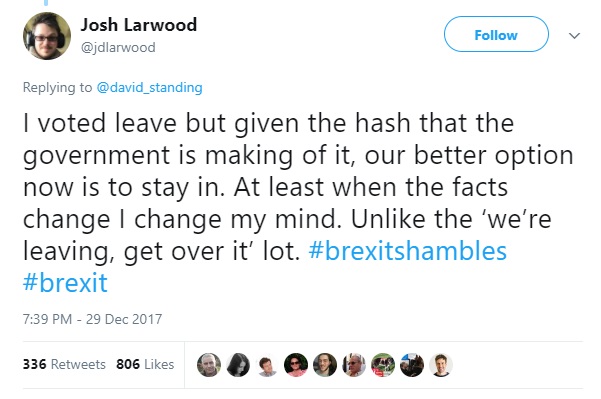

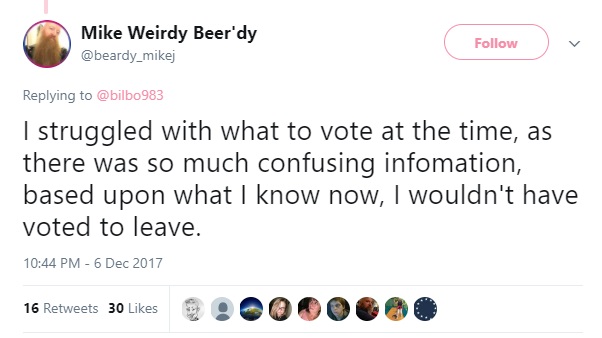

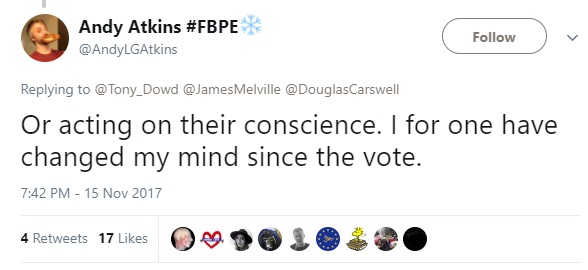

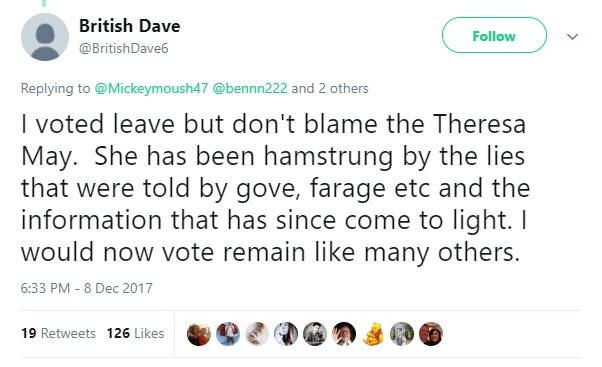

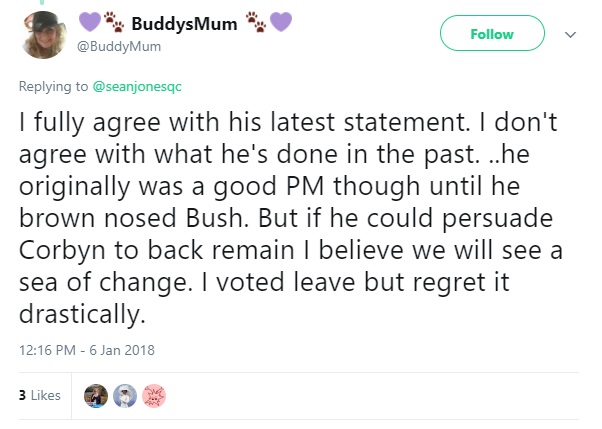

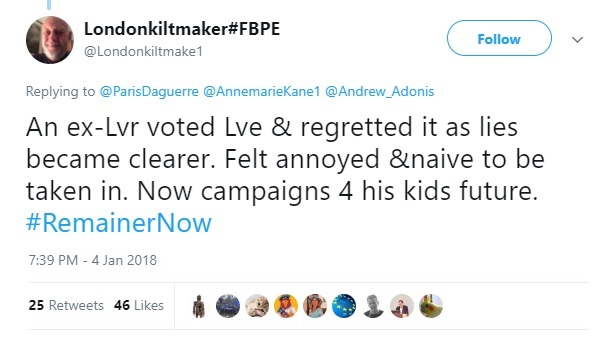

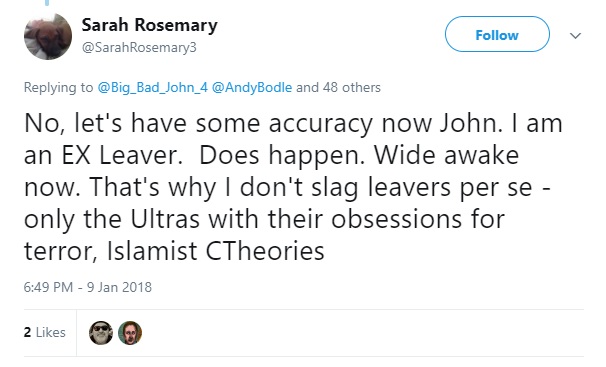

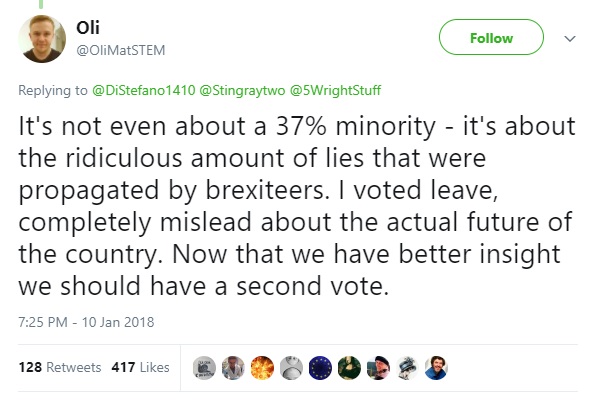

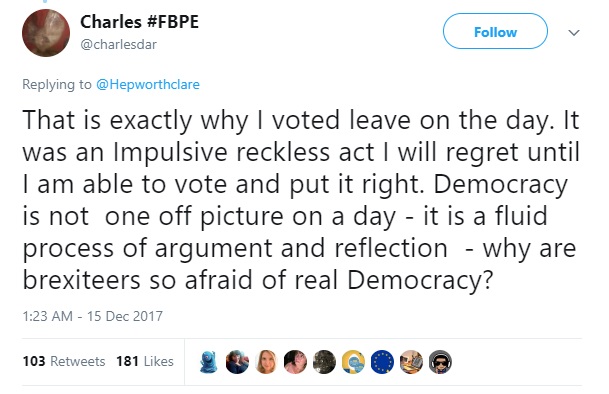

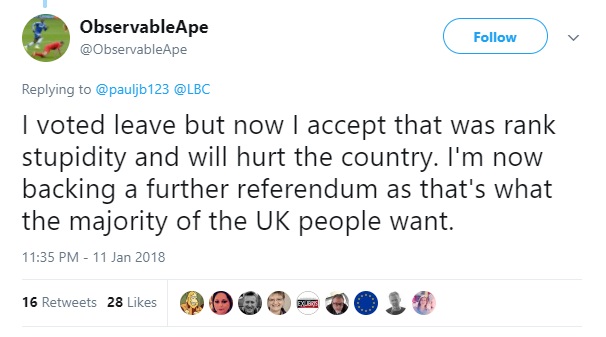

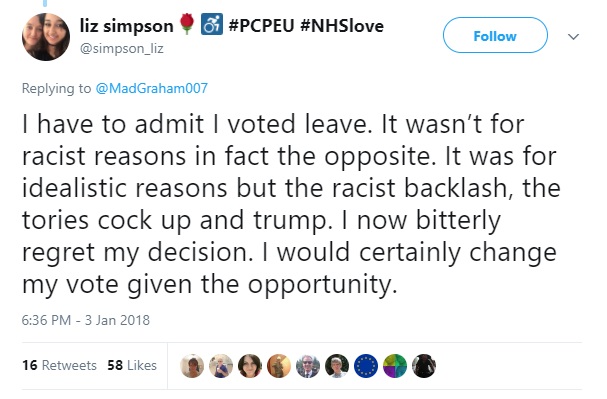

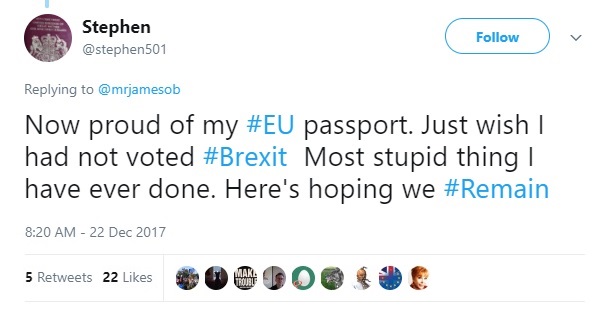

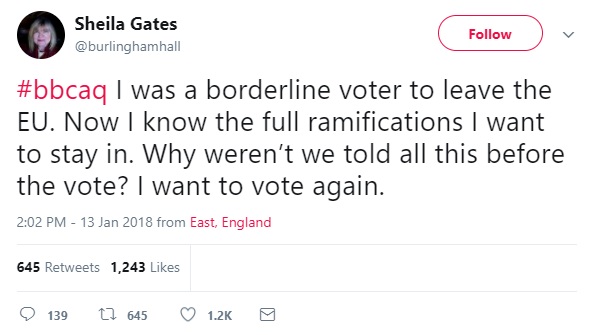

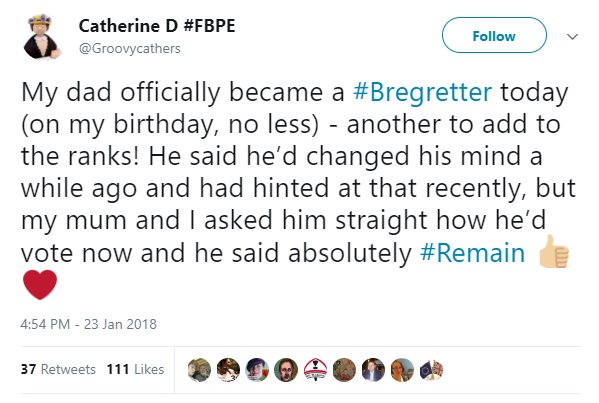

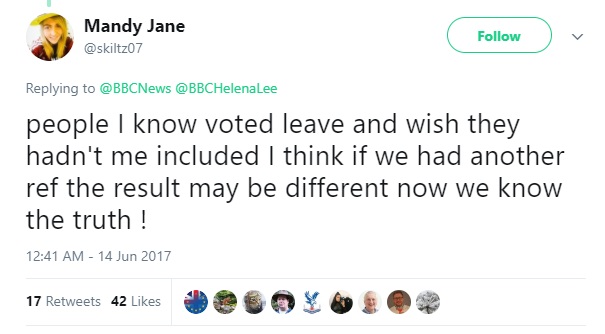

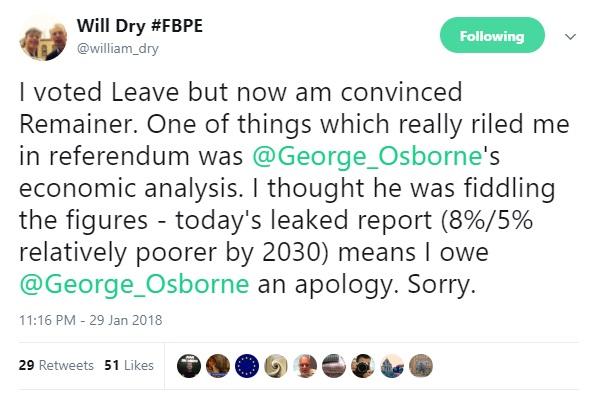

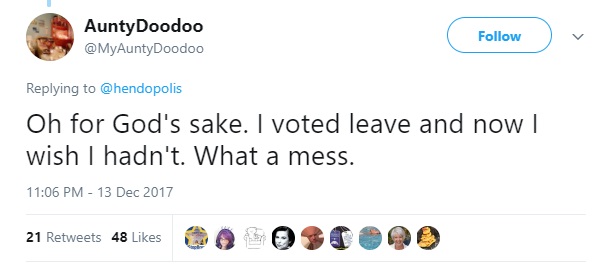

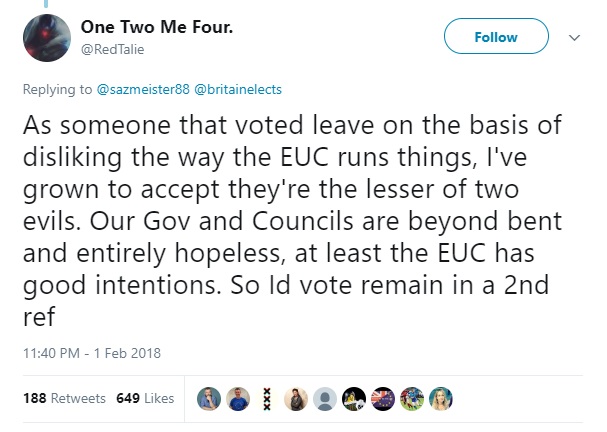

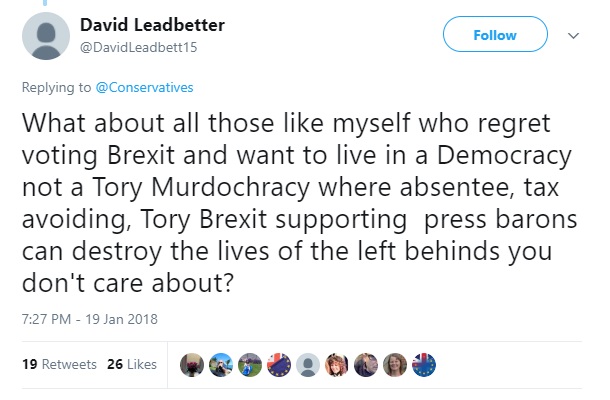

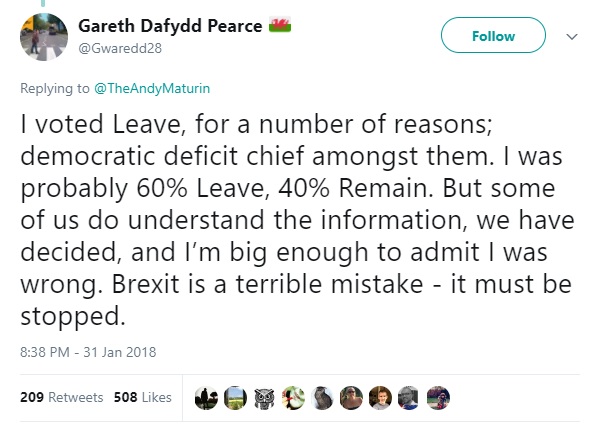

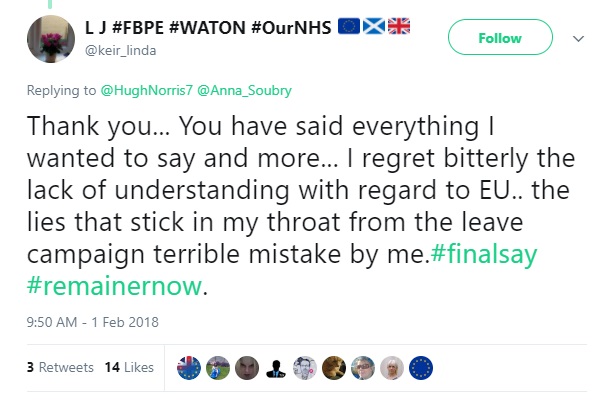

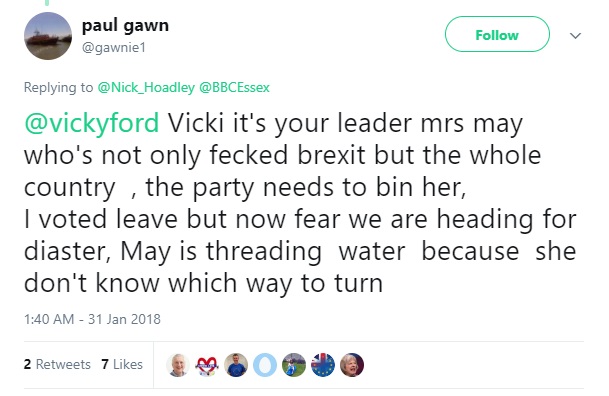

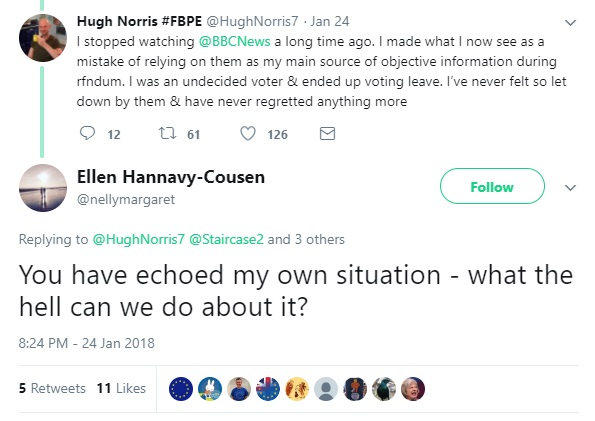

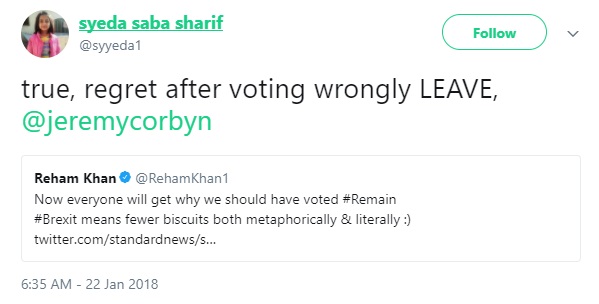

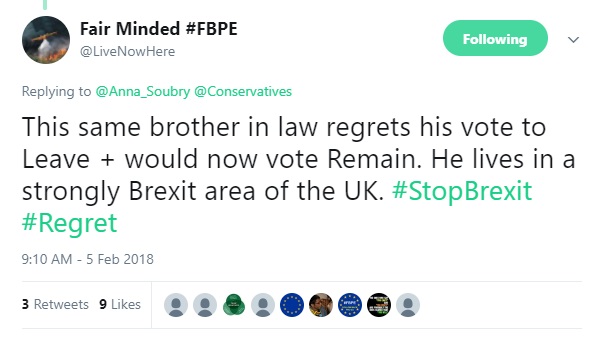

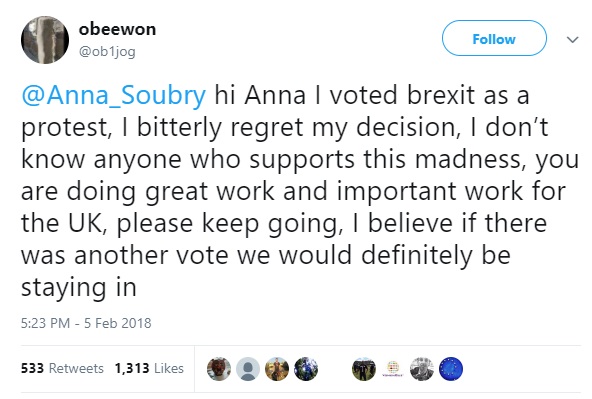

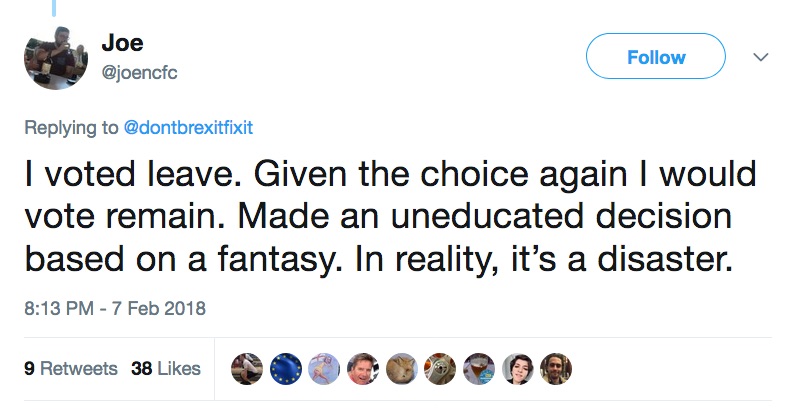

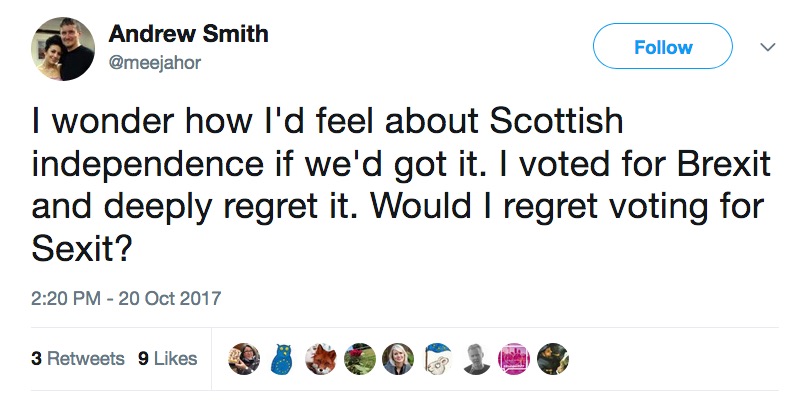

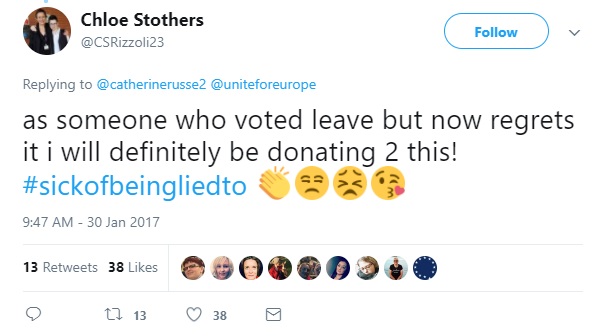

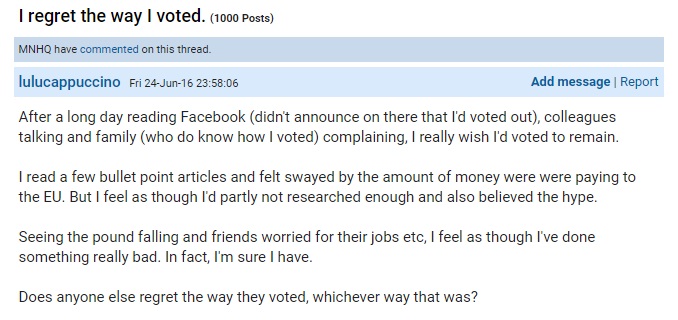

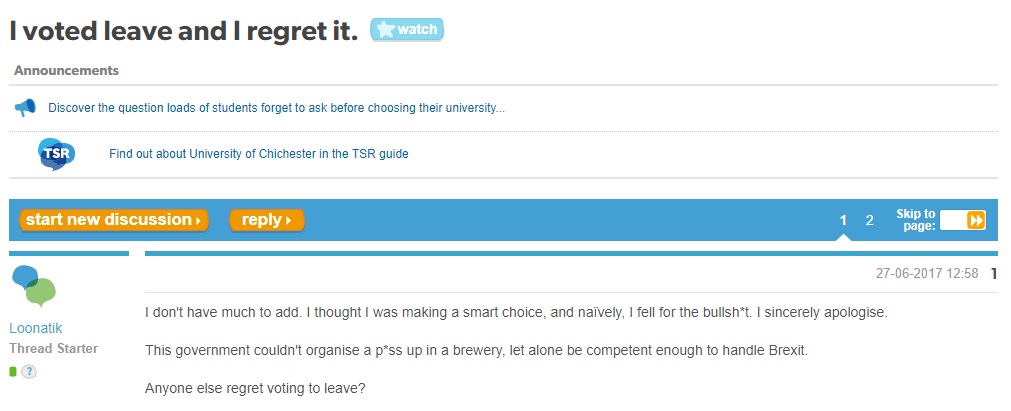

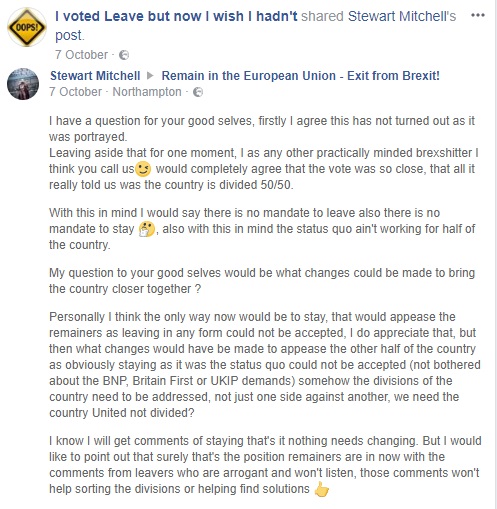

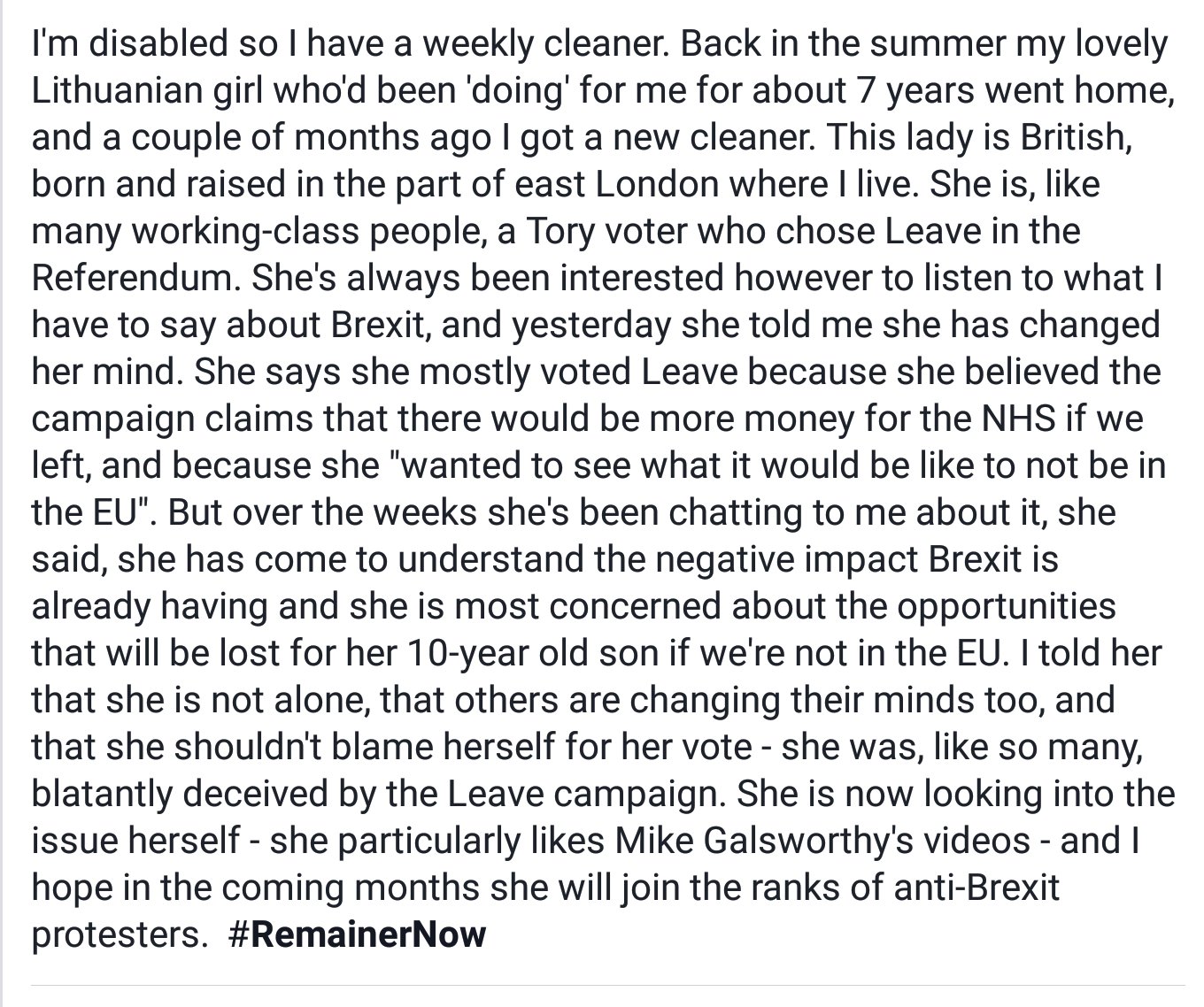

In the interests of fairness, I’ll only count this as one more Remainer. (PS: thanks for your bravery and honesty, Simon!) In any case, this is only supposed to give a general picture of the momentum building against a hasty and calamitous exit from the EU.

In the interests of fairness, I’ll only count this as one more Remainer. (PS: thanks for your bravery and honesty, Simon!) In any case, this is only supposed to give a general picture of the momentum building against a hasty and calamitous exit from the EU.