“Apt analogies are among the most formidable weapons of the rhetorician” – Winston Churchill

For too long, too many people have been listening to populists: know-nothing blatherskites offering simple solutions to complex problems. As a result, the UK has left the EU, nutsacking the economy and the opportunities of the young and triggering a massive rise in racial and class hatred; Jair Bolsonaro has laid waste to the Amazon rainforest; and Americans have elected an incompetent, incontinent, incoherent pussy-grabbing golf cheat as president.

How did the far right achieve this coup? With lies, mostly; but blatant lies most people can see through. Subtler tinkerings with the truth are far more effective.

In 1987, the French scholar Françoise Thom wrote an essay describing the Newspeak-style “wooden language” that the totalitarian regime of Soviet Russia used to fob off, confuse and pacify its citizens. (Orwell’s Newspeak was based on a similar idea of language as an instrument of control.) She identified four main characteristics:

- use of abstract terms over concrete – attractive-sounding but empty slogans (think “Brexit means Brexit”, “Global Britain”, “Take back control”, “Get Brexit done”, “levelling up”), and vague terms like “sovereignty” and “democracy” and “freedom” that sound great but signifiy nothing;

- Manichaeism – nuance-free, black and white thinking that paints everything as a battle between right and wrong, good and evil: “You’re either with us or against us”, “Enemies of the people”, “You lost, get over it”, “Get behind Brexit”;

- tautology – repetition of the same idea: “20,000 police officers”, “40 hospitals”, most of the above catchphrases;

- bad metaphors.

Since the first three are all pretty self-explanatory, it’s the last one I want to look at.

You may recall learning about similes and metaphors in English lessons. Quick refresher: a simile is a figure of speech that compares one object to another using the words “like” or “as”; a metaphor does the same thing, but by saying the two things are one and the same. So “My love is like a red, red rose” is a simile, while “Love is a battlefield” is a metaphor.

(While, strictly speaking, similes, metaphors and analogies are different things, their difference is largely in form, not function, so I’ll be using the terms more or less interchangeably.)

But it turns out metaphors aren’t just for Robert Burns and Pat Benatar. They underpin the very way we think, and if misused, can actually change what we think. A bold claim, I know. Bear with me.

Why do we use metaphors? In 99.9% of cases, they’re an explanatory tool. Metaphors tend to describe something that is less familiar to the listener in terms of something that is more familiar. The unfamiliar quantity – what psychologist Julian Jaynes (pdf) called a metaphrand, but which is now usually referred to as the target – might be an abstract concept (say, love), a complicated or disputed thing (the EU), or a brand-new thing (like coronavirus). The familiar quantity – the metaphier, or source – will generally be something concrete, which we regularly encounter in everyday life: a rose, a football match, influenza. So in “Love is a battlefield”, “love” is the target, the unfamiliar thing, and “battlefield” is the source.

The point is, we can easily summon a mental picture of battlefields and roses and football matches, and most people have some experience of the flu. We have much more trouble visualising abstract, complex and new things, like love, the EU and coronavirus, so people naturally turn to analogies to demystify them. The catch is that some metaphors do not work as advertised.

Two things determine the quality of a metaphor: the accuracy of the comparison, and its richness – the number of ways in which the things resemble each other. Shakespeare’s “All the world’s a stage” is a good metaphor because there are parallels galore between the stage and everyday life (not that surprising when you consider the stage was created as a representation of the world). Bill explores some of them himself: men and women are like actors, playing roles rather than living out their desires; they enter life, and they leave it, just as actors enter and exit the stage; the various phases of life are a bit like the acts of a play.

If, on the other hand, you’d never heard of sulphuric acid, and I explain it to you by telling you it’s a bit like water, you’ll be justifiably mad at me after you drink it (and survive). Ditto if you encounter your first snake, and I say, “Don’t worry, it’s just a big worm.” Bad metaphors can bite.

If anything ever called for a judicious analogy, it was Brexit. Few people – myself included – understood the full detail of how the EU worked, what the benefits of membership were, what the trade-offs were between sovereignty and trade and geopolitical harmony, and how integrated the UK was in EU supply chains. The far right was quick to fill this gap; two of their metaphors have framed much of the Brexit debate.

1. Oppression/confinement/freedom

“EU dictatorship.” “EU shackles.” “Take back control!”

2. Sport/war

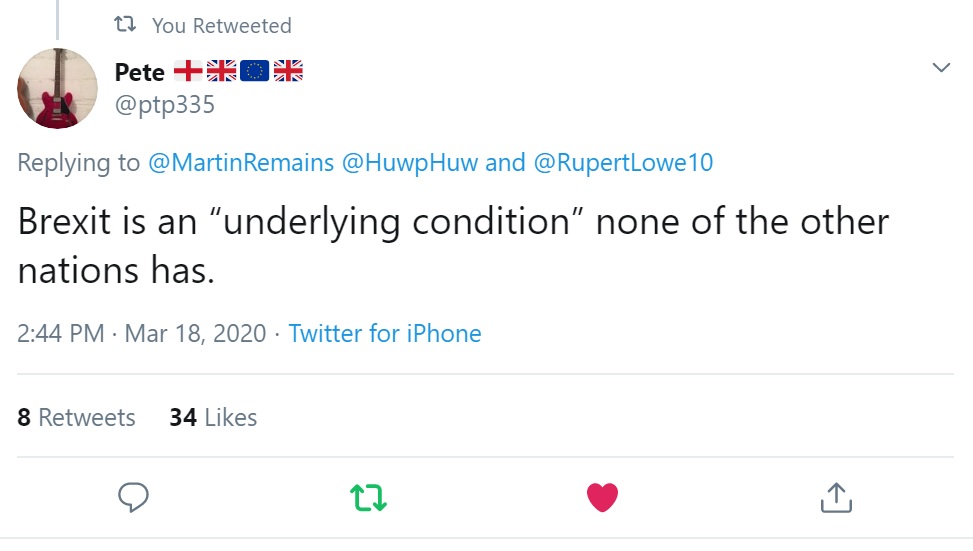

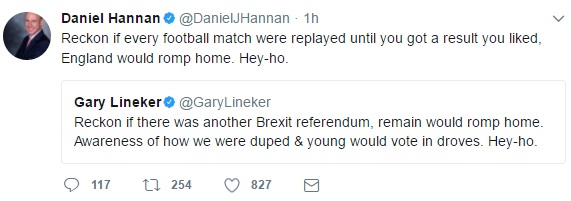

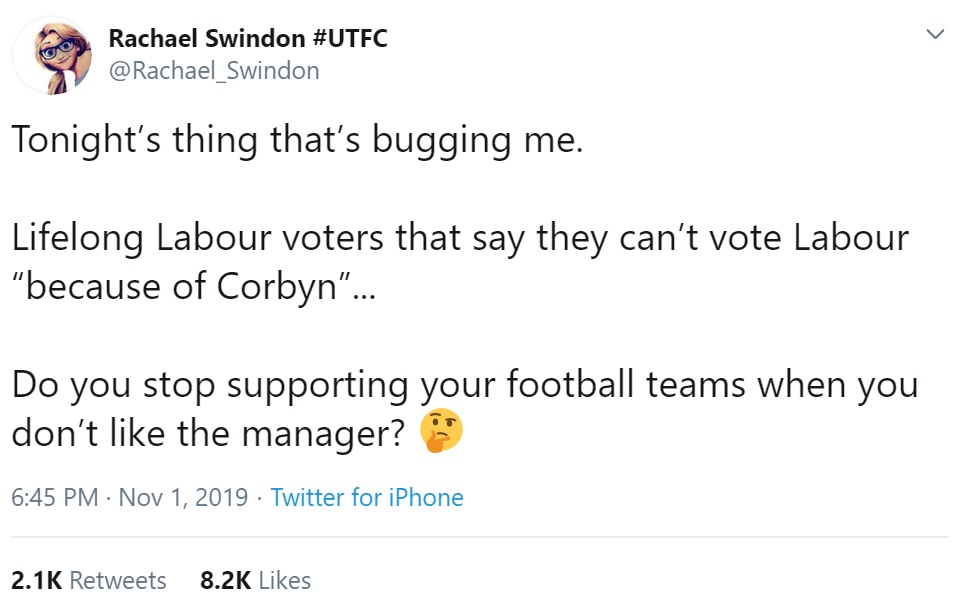

“You lost, get over it.” “You just want a replay until you get the result you want.”

These are superficially powerful lines, which conjure vivid images and cut straight to our sense of self. But as soon as you interrogate them in any detail, they fall apart.

In what respects does the EU resemble a dictatorship? Well … it does take some decisions on its members’ behalf; but it consults its members on those decisions. Members vote on all laws and can veto them. And oftentimes, those members ignore the decisions without sanction.

There are no votes in a dictatorship. They’re run by self-appointed tyrants who tend to reign for life, and they’re characterised by the use of force, propaganda, and an intolerance of opposition and independent media. Dissent is ruthlessly suppressed. And crucially, no one is free to leave a dictatorship.

None of these things apply to the EU, and yet the Brexit gibberlings would have you believe that Guy Verhofstadt is Hitler reincarnated. The propagandists tried to persuade us that the worm was a snake, and a lot of us swallowed it.

Now, in what respects did the EU referendum resemble a football match? A few simple follow-up questions – “What have you won? What have I lost that you haven’t lost too?” “What role did you play in this glorious victory?” “Where do the people who voted leave but have since change their minds fit in, and the handful of remainers who have swung the other way? Are they winners, or losers?” “If your team gets beaten by another one, do you suddenly give up on your team and start supporting the other side?” – expose this comparison as equally flimsy.

When remainers pointed out the possible pitfalls of Brexit, the populists pooped out yet another crap analogy. “Millennium bug!” they chirped. “People issued dire warnings about that, and nothing happened!” Yes, it’s true that then, as now, some people prophesied doom. But that’s literally the only parallel between the two situations. The actors were different, the conditions were different, the entire realm of knowledge was different, the problem was different, and the solutions were different. And crucially, in the case of Y2K, steps were taken to mitigate its effects, without which catastrophe might well have struck.

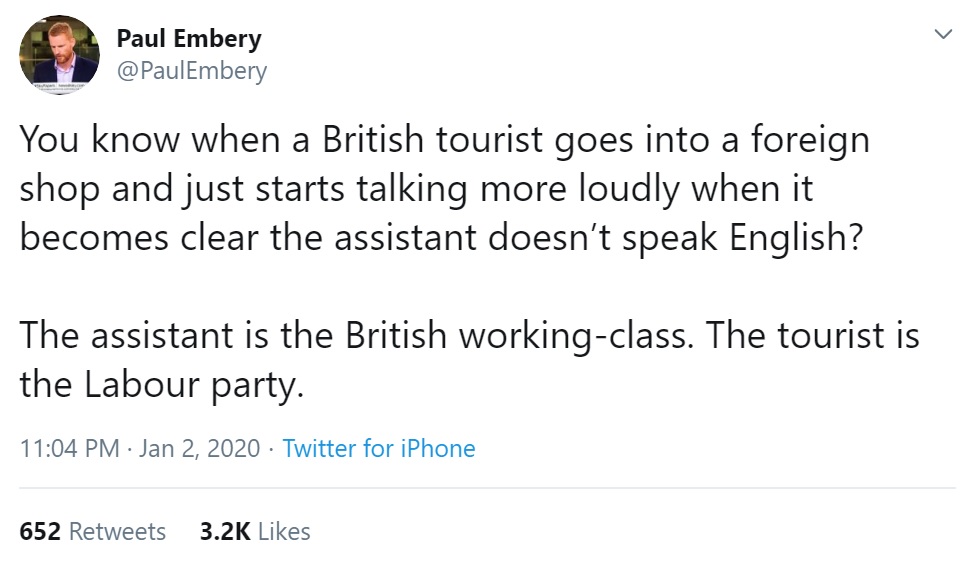

(It’s not just the far right that is guilty of this; the populist, pro-Brexit far left also seems to have a predilection for teeth-grindingly terrible comparisons.)

Remainers did hit back with some counter-metaphors – membership of the EU is more like belonging to a golf club, they said: if you stop paying your dues, you no longer get to play on the course or drink in the bar. But it was all too feeble, too late. The right’s shit metaphors had forced their way into enough people’s heads, put down roots, and become unassailable truths.

And as if that wasn’t enough for them, the populist demagogues and disinformants, emboldened by their Brexit “success”, continued to wheel out their cack-handed comparisons in response to the coronavirus.

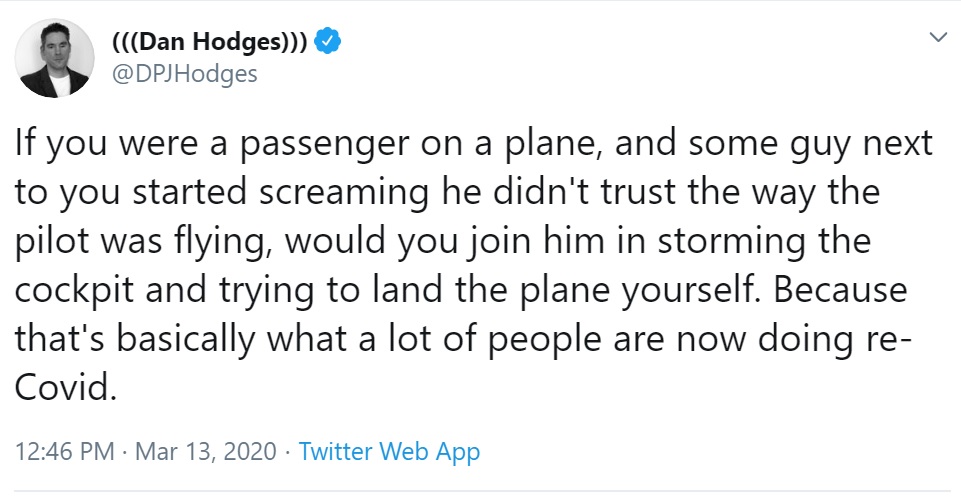

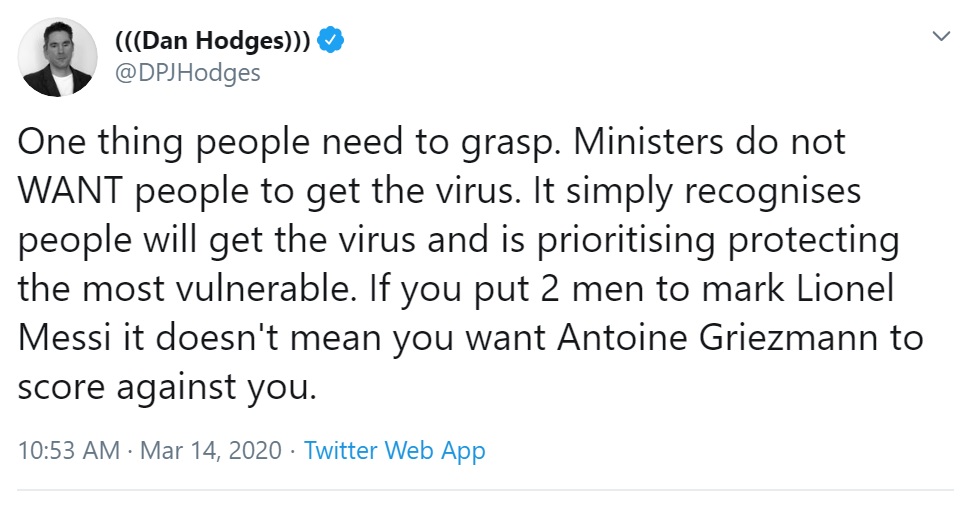

Mail on Sunday dross geyser Dan Hodges can’t help himself; he genuinely seems to consider himself a maven of metaphor, the Svengali of simile.

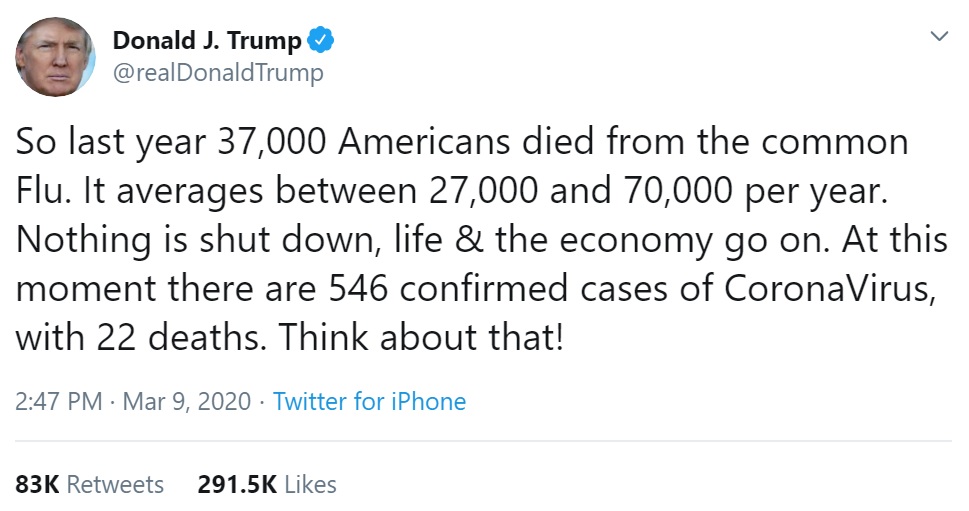

But in their perpetual, desperate quests for attention and relevance, Trump and Brexit party banshee Ann Widdecombe had to go one further.

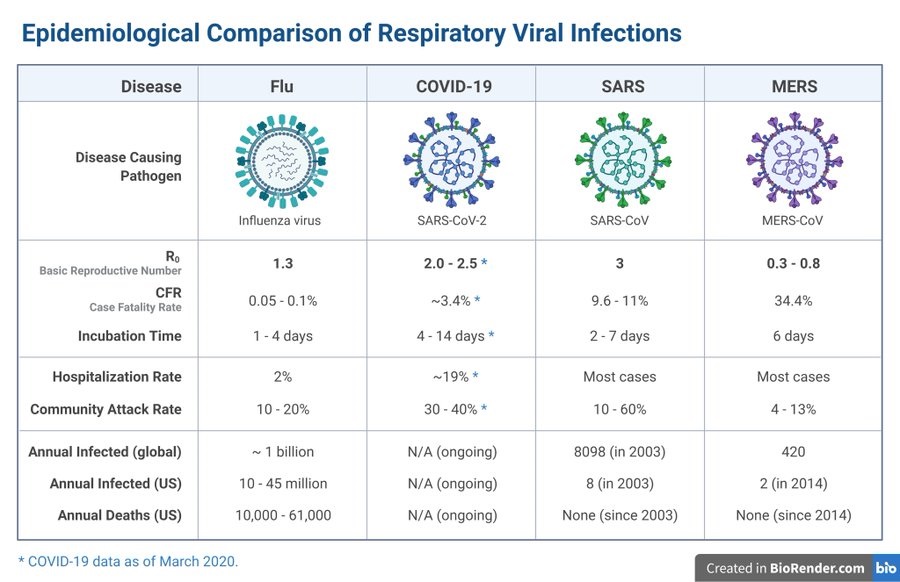

Covid-19 and influenza are both contagious respiratory illnesses caused by a virus, but that’s as far as the similarities go. The symptoms are different, the infection rates are different, the morbidity rates are different, and the treatments are different. The viruses aren’t even part of the same family.

As for the Aids comparison, where to begin? Aids isn’t even a goddamn virus (it’s the final, often fatal stage of the illness caused by HIV).

Trump and Widdecombe’s offhand disinformation goes beyond simple irresponsibility and borders on criminal negligence. Hard though it is to credit, there are people out there who have faith in their wisdom, and they’re repaying their fans by putting their lives in grave danger. (The Express presumably figured this out eventually, or caved in after massive outcry, as it took the Widdecombe column down, which is why I could only screenshot the New European’s response.)

They’ve been at it in America for a while, of course. Anyone who has politely suggested to a gun nut that US gun laws might be a tad on the lax side will be familiar with this retort: “Well, cars kill people too, and no one talks about banning them!”

The problem with this analogy, once again, is that it is fucking shit. Cars are not expressly designed to kill people. Their primary purpose – conveying people and goods from place to place quickly and efficiently – is so damned useful that society has reluctantly decided tolerate the occasional accidental death. Besides, driving is subject to all sorts of rules and regulations. You can’t drive under a certain age, you can’t drive drunk, and you have to obey speed limits and the rules of the road.

“Hold your horses, Bodle – aren’t you getting your panties in a bunch over what are, at the end of the day, just words?” you cry, mixing three metaphors.

But as Hitler and Goebbels knew, as Orwell knew, as the Russian security services and Cambridge Analytica have long known and as others are finally slowly realising, words matter. In an ever more compartmentalised and specialised world, we’ve become unprecedentedly reliant on others for information. On matters we haven’t personally mastered, we have to trust someone. And terrifyingly, a large swath of the population has stopped trusting experts and instead turned to populists and their sloppy, misleading, and often downright dangerous metaphors.

Why am I so concerned about metaphors in particular? Because they’re sneaky. When you encounter a fresh metaphor, it brings you up short. “That’s odd,” thinks your brain. “Not seen that before,” and you take a closer look. If I say, “British shoppers in 2020 are locusts,” you’ll probably spend a couple of seconds weighing it up before deciding whether or not you agree.

If enough people agree with a metaphor, it might catch on, and pass into wider use. So when you read “The elephant in the room” (a metaphorical phrase that dates to the 1950s) or “Take a chill pill” (early 1980s), it’s familiar enough that it no longer has the same jarring effect – you don’t for a second imagine that anyone’s talking about a real pachyderm squatting in your lounge – but still novel enough that you are aware of its metaphorical origin. Now it has become a cliche; if it’s lucky, it might even get promoted to idiom. And when idioms stick around for long enough, a further stage of evolution occurs, and they become part of everyday speech.

The language of abstract relationships – marriages, friendships, etc – almost exclusively borrows the vocabulary of physical relationships. So we talk about the ties between people, breaking up with someone, being close to someone and growing apart. We talk about grasping an idea and beating an opponent and closing a deal. You’ve probably rarely, if ever, reflected on the metaphorical origins of these phrases when using them.

And if you talk about time in any meaningful sense, you will find yourself drawing on the lexicon of space. You simply can’t conceptualise it any other way. You go on a long trip. You were born in the 20th century. You look back on your youth. Time passes by.

Julian Jaynes’s theory – and I’ve never seen a better one – is that humans have a “mental space” (not a literal one, obviously), a sort of internal theatre, where we visualise things in order to make sense of them, and that without this spatialisation, we can’t properly think about things at all.

Metaphors are not just for bards and bellettrists – they’re part of everyday speech and thought. A huge number of words we use, especially those for abstract concepts, started life as metaphors, but have become so widely used that they have developed meanings of their own. Our dictionaries now contain hundreds of thousands of definitions that have separate entries for the literal and figurative meanings of words.

In fact, if you look up the etymology of any abstract concept you can think of, the chances are, it originated from a word or words for tangible things or everyday actions. The word “understand”, for example, derives from under- (Old English “among”, “close to”) and standan (stand). “Comprehend”, meanwhile, comes from con- (with) and prehendere, to gain hold of: to take within. “Money” can trace its family tree to Latin moneta (“a place where coins are made; a mint”), while the verb “to be” ultimately comes from the Sanskrit bhu, meaning “grow”, while the parts “am” and “is” come from a separate verb meaning “breathe”.

Metaphors, it turns out, are fundamental to our conception of the world. They play a massive role in shaping the way we think.

Suddenly, the populist far right’s strategy comes into focus. By putting out misleading metaphors like “EU dictatorship” and repeating them until blue in the face, they’re trying to normalise them. To make people forget that they are in fact just opinions, and mould them into self-evident truths.

(It turns out that there is a crucial difference between metaphors on the one hand and similes and analogies on the other. Similes and analogies are upfront about their intentions – they explicitly admit that they are comparisons, subjective judgements, up for dispute. Metaphors, meanwhile, brook no dissent.)

Never trust an analogy from a populist. How can they explain things to you when they’re totally unversed in the subject-matter? How can Ann Widdecombe possibly know how similar coronavirus is to Aids when even she would admit she knows nothing about either? Only recognised experts know the target domain (in this case, epidemiology) well enough to judge what source makes a good or bad metaphor. Populists just pull things out of thin air that feel right, regardless of their accuracy or utility. This is why popular science books are written by scientists, not populists, why popular economics books are written by economists, not populists, and so on.

“Understanding a thing,” according to Jaynes, “is arriving at a familiarising metaphor for it.” So if people are pushing duff metaphors on us, we’re going to misunderstand things – and as we’re seeing with Brexit, Trump, and especially coronavirus, the consequences of that can be grave.

What can you do about it? Well, the next time someone wheels one of these similes or metaphors or analogies, don’t let it pass. Ask them directly: in what respects is the EU like a dictatorship? When they inevitably fail to answer, point out the differences. Extend the analogy until it collapses under the weight of its own absurdity. Even if you can’t get through to them, you might just help prevent someone else who happens to be following the exchange from falling into the same deadly trap.

To finish on a more positive note, here’s how metaphors should be done. Kudos to @ptp335: