• Part 1: ‘Trade with the EU is declining’ (no, it isn’t)

• Part 2: ‘We send the EU £350m a week’ (no, we don’t)

• Part 4: ‘The UK is the fastest-growing economy in the G7’ (no, it isn’t)

Not so long ago, you could go years without coming across a survey. A few folks were dimly aware of a company called Gallup, thanks to Top of the Pops, for which they compiled the charts, but otherwise polling companies were shy little leprechauns that only popped out once every four years to sound out the populace before each general election.

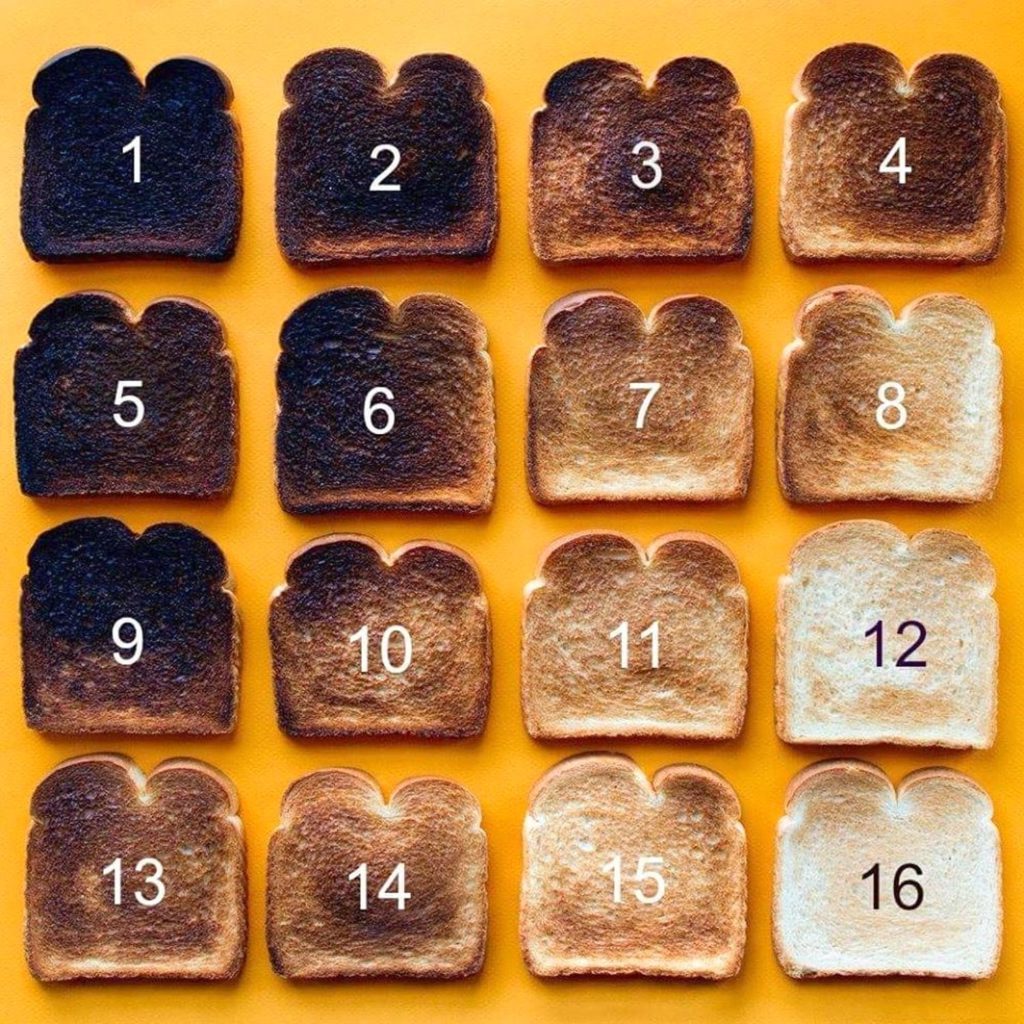

Now you’re lucky if you can go four minutes without seeing a snapshot of public opinion. Twitter polls, website polls, newspaper polls, polls by phone and email and WhatsApp; polls on everything from support for the death penalty to your preferred shade of toast.

What’s my tribe?

The appeal to us plebs is obvious. We can’t get enough of other people’s opinions, whether our response is to nod sagaciously or spit out our tea.

Interestingly, our egos are so devious, it doesn’t much matter whether most people agree with us or not. Because if, according to any given poll, ours is the majority view, we tend to sit back and smirk: “Well, naturally my opinion is the right opinion.” If, on the other hand, we’re in the minority, our response is usually “Gosh, I’m so clever, unlike all these sheep!”

Either way, polls are reassuring because they reinforce our place in the world. Our tribal, hierarchical nature, our teat-seeking need to belong, compels us to constantly reaffirm our sense of identity, and polls give us that in a neat package.

Views as news gets views

If polls are a novelty gift for the hoi polloi, they’re a godsend for newspapers, struggling as they are with dwindling resources, and for rolling news channels with endless airtime to fill. No time-consuming investigation, photography, writing or planning required – the pollsters take care of it all for free, right down to the covering press release with its own ready-made headline finding. And the public lap it up.

The pollsters, of course, are laughing all the way to the bank. Their services are in greater demand than ever before; the polling industry in the UK currently employs 42,500 people – four times as many as fishing.

So, surveys are win, win, win, right? People get entertainment, journos get clicks, pollsters get rich. What’s the problem? Because there’s always a problem with you, isn’t there, Bodle?

Blunt tools

As a matter of fact, there are two. The first is that polls are low-quality information.

Despite having been around for almost 200 years, and despite huge advances in methodology and technology, gauging popular opinion is still an inexact science. For proof, look no further than the wild differences between any two surveys carried out at the same time on the same issue.

In the week prior to the 2017 UK general election, for example, Scotland’s Herald newspaper had the Tories winning by 13%, while Wired predicted a 2% win for Labour. (In the event, May’s lot won by 2.5%; picking a figure somewhere in the middle of the outliers is usually a safeish bet.)

The main headache for canvassers has always been choosing the right people to canvas. If you conducted a poll about general election voting intentions solely in Liverpool Walton, or took a snapshot of views on the likely longevity of the EU from 4,000 Daily Express readers (which the Express continues to do on a regular basis), then presented the results as a reflection of the national picture, you would rightly be laughed out of Pollville.

The key to a meaningful survey is to find a sample of people that is representative of the whole population. Your best hope of this is to make the sample as large as possible and as random as possible, for example by diversifying the means by which the poll is conducted (because market researchers wielding clipboards on the high street aren’t going to capture the sentiment of many office workers or the housebound, while online polls overlook the views of everyone without broadband), and sourcing participants from a wide area.

Even then, you have to legislate for the fact that pollees are, to a large degree, self-selecting. For one thing, people who are approached by pollsters must, ipso facto, be people who are easily contactable, whether in the flesh, by phone or online, which rules out a swathe of potentials; and for another, they’re likely to have more free time and less money (many polls still offer a fee).

Tories, trolls and tergiversators

Even if you do somehow manage to round up the perfect microcosm of humanity, there are further obstacles.

For one thing, people are unreliable. The “shy Tory factor” is well documented; people don’t always answer truthfully if they think their choice might be socially unacceptable. You can mitigate this problem somewhat by conducting your survey anonymously, which most pollsters now do.

Anonymity, however, only exacerbates a different problem. As anyone who has spent five minutes on social media will know, there are plenty of people around who just lie for kicks (or money). And if the questions aren’t being put to you in person, and your name isn’t at the top of the questionnaire, there’s even less pressure on you to tell the truth.

Furthermore, people don’t always know their own minds. If you’re faced with difficult questions in an area where your knowledge is sketchy, like trans rights or Northern Ireland, your honest answer to most questions would be “Don’t know”. But you’d feel dumb if you ticked “Don’t know” every time. Isn’t there a temptation to fake a little conviction?

And (Brexiters and Remainers notwithstanding), people’s opinions are not set in stone. Someone may genuinely be planning to vote Green when surveyed, then change their mind on the day.

Then there’s the issue of framing. Every facet of a survey, from its title to the introductory text, from the phrasing of the questions to the range of available answers, can unwittingly steer waverers towards certain choices.

Let’s say you want to study views on asylum seekers. If you ask 2,000 people “Do you agree that Britain should help families fleeing war and famine?”, you’re likely to get significantly different results than if you ask them, “Do you think Britain should allow in and pay for the upkeep of thousands of mostly young, mostly male, mostly Middle Eastern and African migrants?” (If this seems like an extreme example, I’ve seen some equally awful leading questions.)

Sometimes the questions don’t legislate for the full spectrum of possibilities. If no “don’t know” option is included, for example, people may be forced into expressing a preference that they don’t have.

Finally, the presentation of a poll’s results can make a huge difference. Few people have the patience to read through polls in their entirety, so what happens? Pollsters create a press release featuring the edited highlights – the highlights according to them.

When you consider all these pitfalls, suddenly it’s not so hard to see why pollsters’ predictions often fly so wide of the mark. But … so what if polls are inaccurate? They’re just a bit of fun!

This brings us to my second, more serious concern.

Market intelligence

While they’re passable diversions for punters and convenient space-fillers for papers and news channels, no one ever went on hunger strike to demand more polls. This constant drizzle of percentages and pie charts has not been delivered by popular demand. It’s a supply-side increase, driven by the people who really benefit from it.

Businesses live or die by their market research: the information they gather from the general populace. If you’re a food manufacturer launching a new bollock-shaped savoury snack, for example, it helps to know how many consumers are likely to buy it. But firms are also greatly dependent on their marketing – the information they send back into the community. And one of the best things they can do to promote their product is to generate the impression that by golly, people love Cheesicles!

We simply don’t have the time to do all the research required to formulate our own independent view on every imaginable issue. So what do we do? We take our cue from others: friends, or experts, or people we otherwise trust.

Hence the myriad adverts featuring glowing testimonials from chuffed customers. Hence celebrities being paid astronomical fees for sponsorship deals. Hence the very existence of “influencers”. Like it or not, our opinions are based, in large part, on other people’s opinions.

The only thing more likely to cause a stampede for Cheesicles than the endorsement of a random punter or celebrity is the endorsement of everyone. Why else would a certain pet food manufacturer spend 20-odd years telling everyone that eight out of 10 cats preferred it (until they were forced to water down their claim)? Aren’t you more tempted to give Squid Game a chance because everyone’s raving about it?

Even though some people quite like being classed among the minority – the brave rebels, the “counterculture” – those people are, ironically, in a minority. Most of us still feel safer sticking with the herd. So it’s in manufacturers’ interests to publish information that suggests their product is de rigueur.

(If you’re in doubt about the susceptibility of some people to third-party influence, look up the Solomon Asch line length test. As part of an experiment in 1951, test subjects – along with a number of paid plants – were shown visual diagrams of lines of different lengths and told to identify the longest one. The correct answer in each image was clear, but the stooges were briefed to vocally pick, and justify, the (same) wrong answer – and a surprisingly high proportion of the subjects changed their decision to match the wrong answer given by their peers. Later variations on the same study furnished less clear-cut results, but the phenomenon is real.)

And this is where all those flaws in polling methodology suddenly become friends. Polls can be inaccurate and misleading by accident – but they can also be misleading by design.

When businesses conduct a poll, they can (and have, and still do) use all the above loopholes to nudge the results in the “right” direction. They can select a skewed sample of people. They can select a meaninglessly small sample of people (still the most common tactic). They can ask leading questions, leave out inconvenient answers, present the results in a flattering way – or just conduct poll after poll after poll, discard the inconvenient results, and publish only those in which Cheesicles emerge triumphant.

Woop-de-doo, so businesses tell statistical white lies! Hardly front-page news, or the end of the world. If I’m duped into shelling out 75p for one bag of minging gorgonzola-flavoured corn gonads, well, I just won’t repeat my mistake.

True. But it’s a different story when the other main commissioners of polls play the same tricks.

Offices of state

It cannot have escaped your notice that the worlds of business and politics have been growing ever more closely intertwined. There’s now so much overlap of personnel between Downing Street, big business and the City (the incumbent chancellor, who arrived via Goldman Sachs and hedge funds, is just one of dozens of MPs and ministers with a background in finance), such astronomical sums pouring into the Tory party from industry barons, and so many Tories moonlighting as business consultants, that you might be forgiven for thinking that the two spheres had merged.

And as the association has deepened, so politicians (and other political operators like thinktanks and lobbying groups) have borrowed more tactics from their corporate pals. Public services are run like private enterprises; short-term profits and savings for the few are constantly prioritised over the long-term interests of the many; government communications departments have been transformed into slick, sleazy PR outfits. And one of the tools they’ve most warmly embraced is the poll.

While businesses carry out market research to gauge the viability of their products and services, political parties do so (largely through focus groups) to find out which policies and slogans will go down well. But whereas businesses only publicise polls to create the illusion of popularity, the practice has wider and scarier applications in the political sphere.

“Opinion polls are a device for influencing public opinion, not a device for measuring it. Crack that, and it all makes sense”

Peter Hitchens, The Broken Compass (2009)

Loath as I am to quote the aggressively self-aggrandizing Hitchens, on this occasion, he may have stumbled across a point. A number of studies (pdf) have looked into this phenomenon (pdf), and while the findings aren’t conclusive, they all point in the same direction: people can be swayed by opinion polls.

There are several mechanisms at play. First, if there’s a perception that one candidate in an election has an unassailable lead, some undecideds will back the likely winner, because they think the majority must be right (the “bandwagon effect”); a few will switch to backing the loser out of sympathy (the “underdog effect”); some of those who favoured the projected winner might not bother voting because it’s in the bag, while some of those who favoured one of the “doomed” candidates might give up for the same reason.

Conversely, if polls suggest a contest is close, turnout tends to increase. Even if your preferred candidate isn’t one of the two vying for top spot, you might be moved to vote tactically, to keep out the candidate you like least.

Polling also has an indirect effect via the media. When surveys are reporting good figures for a candidate, broadcasters and publishers tend to give them more airtime and column inches, thus increasing their exposure, and, consequently, their popularity.

However these effects ultimately balance out, it’s clear that the ability to manipulate polling information could give you enormous political power. “But that’s absurd!” you cry. “I’ve never had my mind changed by anything as frivolous as a poll!”

Really? Can you be absolutely sure of that? Even if you’re immune, can’t lesser mortals be affected? If it works in the advertising world, there’s no reason why shouldn’t it work in the political sphere.

You might object at this point that pollsters are legitimate enterprises that have nothing to gain from putting out false information. To which I would counter-object: polling companies are businesses too. They exist not as some sort of public service, but to make money for their clients. And their clients’ interests do not always align with the public good.

A brief look at the ownership and management of the pollsters does little to alleviate these fears.

Savanta ComRes (formerly ComRes)

Retained pollster for ITV and the Daily Mail. Founded by Andrew Hawkins, Christian Conservative and contributor to the Daily Telegraph with a clear pro-Brexit stance. This year, Hawkins launched DemocracyThree, a “campaigning platform” that helps businesses and other interest groups raise funds and build support – ie influence public opinion.

“Democracy 3.0 helps you build a support base, raise the funds you need for your campaign to take off, and then we work with you to appoint professional campaigners – such as lobbyists and PR experts – who can bring your campaign to life.”

DemocracyThree website

ICM

Co-founded in 1989 by Nick Sparrow, a fundraising consultant who worked as a private pollster for the Tories from 1995-2004. Now part of “human understanding agency” Walnut Unlimited, which is in turn part of UNLIMITED – a “fully integrated agency group with human understanding at the heart”.

The sales pitches for these firms include the following quotes:

“Our team are experts in public opinion, behavioural change, communication, consultation and participation, policy and strategy, reputation, and user experience.”

ICM website

“We help brands connect with people, by understanding people … Blending neuroscience, behavioural science and data science, we uncover the truth behind our human experiences … Our mission is to create genuine business advantage for clients … by uncovering behaviour-led insights from our Human Understanding Lab.”

Walnut Unlimited website

Populus

Official pollster for the Times newspaper, co-founded by Tory peer Andrew Cooper and Michael Simmonds, a former adviser to the Tory party now married to Tory MP Nick Gibb, who has recently been added to the interview panel to choose the next head of media regulator Ofcom.

YouGov

Founded by Nadhim Zadawi, the incumbent Tory health secretary, and Stephan Shakespeare, former owner of the ConservativeHome website and former associate of diehard Brexiters Iain Dale, Tim Montgomerie and Claire Fox.

Survation

Founded by Damian Lyons Lowe, who during the EU referendum campaign set up, at the request of Ukip’s Nigel Farage, a separate “polling” company, Constituency Polling Ltd, based in the Bristol office of Arron Banks’s Eldon Insurance. But its remit seems to have been less about asking questions and more about micro-targeting voters. “Interviews with several people familiar with Survation’s operations show that in addition to measuring public opinion, the firm’s executives also helped shape it.”

(I was unable to find any evidence of strong political affiliation among the leadership of Ipsos MORI or Qriously, and Kantar has changed ownership and CEO so frequently of late as for any such investigation to be meaningless. As a side note, there seems to have been a recent flurry of activity in this sector, with many companies being gobbled up into ever larger, faceless global marketing conglomerates, whale sharks hoovering up data, with ever more sinister specialisms: “consumer insights”, “market intelligence”, “human understanding”.)

I don’t know about you, but I’d expect the people who founded and run companies that were nominally about gathering and analysing data to be statistics nerds – people with an interest in objective truth – not, by an overwhelming majority, people with the same strong political leanings. Put it this way: CEOs of polling firms have final approval over which surveys are released. If you were married to a Tory MP, would you really sign off on a poll that was damaging to your husband’s party?

Someone of a more cynical bent might start wondering whether the hard right, having secured control of most of the UK’s print media and with its tendrils burrowing ever deeper into the BBC, was stealthily trying to establish a monopoly on data.

So maybe they’re not all angels. But surely they can’t just pump rubbish into the public domain willy-nilly? In a stable(ish) 21st-century democracy like Britain, there must be checks and balances in place.

Well, here’s the thing. Businesses are prevented from publishing grossly misleading adverts by the Advertising Standards Authority, but there’s no such independent regulator for the polling industry. They police themselves, through a voluntary body called the British Polling Council, staffed entirely by industry members.

So, polls are bad information, they can influence people’s votes, the pollsters’ motives are questionable, and they’re accountable to no one. But what about journalists? Isn’t it their job to pick up on this sort of thing?

It is, but as I mentioned above, journalistic resources are so depleted now, and the pressure to get stories up fast so great, that they can ill afford to look gift stories in the mouth. And as I mentioned in my last post, journalism and broadcasting aren’t exactly brimming with Carol Vordermans. Even if they had the time and the inclination to carry out due diligence, they wouldn’t necessarily know how.

The bald fact is, when you look at a poll, whether it’s reached you through a newspaper, a website, a meme or a leaflet, you have no guarantee whatsoever that it’s been subjected to even rudimentary checks.

What can we do?

Surveys are – or were, originally – designed to present a snapshot of the popular mood. But even the most fair-minded, honourably intentioned, statistically savvy pollster, using the best possible methodology, can produce a poll that is complete and utter Cheesicles.

But judging by the vast amounts of money pouring into the industry, the political leanings of its ownership and management, and their alarming transformation from simple question-setters to behavioural change specialists, there’s a very real possibility that honourable intentions are an endangered species in the polling industry.

Polls aren’t going away any time soon. Businesses and politicos will always want to gauge which way the wind is blowing. But when it comes to the data they’re pumping back in the public domain – a tiny fraction of what they’re amassing – the rest of us don’t have to play along.

To journalists, I would say: please stop treating polls as an easy way of filling column inches. (Employees of the Daily Express, Mail, Sun and Telegraph, I’m not talking to you. I said “journalists”.)

This is the opposite of speaking truth to power; it’s speaking garbage to those who aren’t in power. It’s 1980s women’s magazine journalism, clickbait, guff, and you’ve repeatedly proven yourselves incapable of discerning good information from bad.

If you must run an article on a poll, then ensure that, at the very minimum, you ask, and get satisfactory answers to, these questions:

- Who commissioned the poll?

- Who carried out the poll?

- What was the sample size? If it’s much less than 2,000 people, ignore it.

- What’s the relative standard error? (A measure of the confidence in the accuracy of the survey. If Labour are leading the Tories in a poll by 36% to 35% and the RSE is over 2% – as it is on samples of less than 2,000 – then they may not be leading at all.)

- What were the questions?

- What was the methodology?

Then, when you publish the story, include all this information so that readers can draw their own conclusions about the poll’s reliability. Above all, include a link to the poll. If you don’t take all these steps, your story is worthless.

To the public, my advice would be: ignore polls. If you must read them, treat them as meaningless fun, fodder for a throwaway social media gag, and don’t for one second fall into the trap of thinking they’re conveying any sort of truth.

If you’re ever approached to participate in a poll, ask yourself: do you really want to be handing over your data to people who are likely to be using that data against you and enriching themselves in the process?

Finally, to the pollsters, I would say: we’ve got your number.