Meep-meep to MAGA: how Road Runner paved the way for Trump

Is it any surprise that kids don’t want to learn when the learned are routinely portrayed as asexual, autistic archvillains?

So what is driving this new climate of distrust, bordering on outright hostility, towards people who think?

History shows us that populist surges generally follow periods of economic hardship, war, or both. We all know what happened in the 1930s after the Great Depression, but a similar pattern of events can be seen in the rise of Andrew Jackson after the downturn of the 1820s and in the aftermath of World War Two. As discontent grows, so does anger towards those in charge – whether they are responsible or not – and clever folk are usually part of that establishment. The time is ripe for other interest groups, usually those who have been sidelined from power, to step in and widen the cracks.

And there are always plenty of such candidates in the wings. As Richard Hofstadter notes, the impetus for anti-intellectual movements usually comes from one of three directions: big business, which rarely appreciates transparency; the church, whose very existence is threatened by concepts such as reason and evidence; and the nationalist right wing, which depends heavily on misinformation to get its message across.

These people aren’t exactly pushing at a locked door. The latent scorn for experts among the inexpert population is never far below the surface.

There’s one area that Hofstadter conspicuously glosses over in his analysis: culture. And yet for the most illuminating insights into a society, it helps to look at its fictions as well as its facts. Hence this post.

In western culture, real men don’t think. (It should become obvious in a few paragraphs why I’m only talking about men here.)

From the oldest folk tales to the latest TV shows, the heroes of British and American stories have overwhelmingly been men of action rather than people of learning: King Arthur. Robin Hood. Flashman. Hornblower. Jack Aubrey. Sharpe. Tarzan. Flash Gordon, Buck Rogers and virtually every comic-book character. Dick Barton. Dan Dare. Biggles. Bond. Roy of the Rovers. Starsky and Hutch … Men of courage, men of heart, honourable and true, but none of them likely to appreciate a subscription to the London Review of Books.

They are brave to the point of recklessness; chisel-jawed, dimple-chinned, gung-ho, love their mothers, love their country. They’ve rarely spent any time acquiring any of their prodigious skills; they’re just born that way. And usually, to be frank, they’re titanically dull, relying on quirky sidekicks for any entertainment beyond the thud of fist on jaw.

They might be possessed of a certain resourcefulness, a dry wit or cunning, but they are never learned men. They’re the first person you want to call when trouble breaks out – but the last you’d want on your Only Connect team.

More recently, Anglo-American culture has thrown up a second type of hero: the lovable rogue. In this category you have Molesworth, Just William, Bertie Wooster, Dennis the Menace, Minnie the Minx, Del Boy, Arthur Daley, Norman Stanley Fletcher, Homer Simpson. These characters aren’t just ambivalent about intellectual enrichment; they’re actively averse to it. They too survive on native wit and luck rather than on any insights they might have picked up by study or observation.

In terms of popular protagonists with actual brains, all I could come up with (after an admittedly cursory thunk) was Doctor Who and Iron Man. I’m discounting detectives – Holmes, Marlowe, Marple, Morse, Columbo – as brains are kind of the sine qua non in a crime solver.

(It’s perhaps worth noting that both Tony Stark and the Time Lord come to us as fully formed geniuses. Their brilliance is cool only because it is effortless. Stark magically knows everything despite spending his every spare moment partying and banging hot chicks, and the Doctor is an alien who picked up his magisterial knowledge before we met him. While you can bet a pound to a penny that any film about sporting prowess will feature at least one montage showing our hero training earnestly for the Big Match or Fight, cerebral heroes are never shown putting in the unglamorous work that got them where they are.)

There seem to be two roles reserved for bright characters in western fiction. The most common is socially inadequate, undersexed oddball sidekick: Willow from Buffy, Mr Spock*, Flash Gordon’s Dr Zarkov, Dan Dare’s Professor Peabody, Hermione from Harry Potter, Thunderbirds’ Brains – so narrowly defined by his mental acuity that he’s never given a real name – and Bond’s Q. While the hero kicks butt and pumps booty, these poor souls toil thanklessly in the shadows, emerging only to deliver their (often crucial) findings when the hero requires them.

* Thankfully, The Next Generation flipped the Kirk-Spock dynamic with Picard and Riker.

The other part the genius regularly gets to play, of course, is the bad guy. Dr Frankenstein, the archetypal mad scientist. Bond’s various evil-genius enemies. Dennis the Menace’s nemesis, Walter the Softy. The Mekon. The Bash Street Kids’ Cuthbert Cringeworthy. Street-smart Will Smith’s preppy punchbag cousin Carlton in The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air. None of these are helpful depictions for academics who are mostly trying to make the world a better place.

So far, so depressing. To my mind, there are two fictional universes in particular that encapsulate society’s unhealthy attitude towards its brainboxes.

The Looney Tunes cartoons featuring Wile E Coyote and the Road Runner, which initially ran from 1949 to 1966, were a straight-up battle between ingenuity and common sense, between artifice and natural ability. And who wins out every time? Wile E Coyote’s ingenious traps, courtesy of the Acme corporation, always end up blowing up in his face, while a combination of raw speed and luck allows the Road Runner to live to meep another day.

Intentional or not, the message is hammered home as surely as Wile E’s skull is pounded into the Arizona dust: instinct trumps science every time. Those with ideas above their station will pay the price for their arrogance; far better to accept your natural place and your natural gifts. The coyote, as the rightwingers and religious nuts see it, would have more luck if he just used his God-given animal instincts.

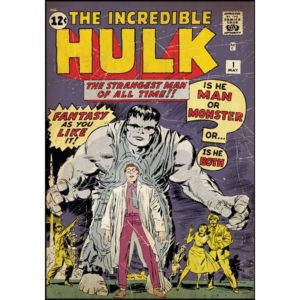

Then, in 1962, a character came along who distilled the brain/brawn dichotomy into a single body. Under normal circumstances, he’s Bruce Banner: a (supposedly) brilliant scientist, but weedy, emotionally distant, indecisive, ineffectual. But subject Bruce to stress, and he undergoes a priapic transformation into the Hulk: an unstoppable, unkillable powerhouse of limitless strength who’s barely able to form a sentence. Sure, Banner can recalibrate your mass spectrometer or fix the frizz on your TV, but if when the real shit goes down, there’s only one guy you want around. Once again, the primal, “natural” persona wins out over the modern, reflective soul.

There’s been precious little to counter this narrative. Sure, the cerebrally unchallenged have mounted mini-fightbacks in the films of John Hughes (The Breakfast Club, Weird Science) and more recently under the direction of Judd Apatow, and the words “geek” and “nerd” have been somewhat reclaimed, thanks in part to the terrifying success of the Silicon Valley tech elite. But even today, the stereotypical image of the educated person is of a friendless introvert who, while gifted in one department, can’t win an arm-wrestle, change a lightbulb, or get laid in a Bangkok brothel.

For every Good Will Hunting, there are 100 Ethan Hunts; for every Dead Poets Society, 50 Fight Clubs. Given the bombardment of negative stereotypes around learning and diligence, it’s no wonder a good 75% of my male peers spent most of their schooldays twanging the girls’ bra-straps and carving FUCK into their desks instead of developing their mental abilities. Nor is it a huge surprise when the likes of Nigel Farage waves away 60 years of universally accepted medical research to insist that smoking is perfectly safe. (Here, Nige, have another. Go on, be a devil.)

Some will protest that art imitates life rather than shaping it. This is true, but in reflecting stereotypes, culture also reinforces them. And when our stories offer so few positive role models of a particular type, what hope is there that things will change?

Coming up: how does an intellectual David take on Goliath?