The Brexit index

A nexus for all the best articles, blog posts, tweets and other resources related to the ongoing clusterfuck

Immigration and freedom of movement

Fake thinktanks, data harvesting and targeted propaganda

Role of the social media giants

Populist tricks and how to see through them

Are people changing their minds?

As loyal reader (not a typo) will know, I’ve compiled a fair bit of material about Brexit and the rise of populism on this site. But there are of course plenty of others with more knowledge and a better work ethic than me, so there’s a veritable glut of information out there now. Only thing is, it’s all so … scattered. So this page will serve as a nexus for all the best articles, blog posts, tweets and other resources related to the ongoing clusterfuck.

It will of necessity be fairly skeletal to be begin with, as I wanted to get it up sooner rather than later, but I hope it will grow quickly – ideally with your help. Feel free to suggest any links you’ve found useful. (And don’t be upset if I don’t use them straight away. I don’t have as much time or energy to spend on this as I’d like.)

What is the European Union?

Newsbeat version (for Brexiters)

European attitudes to the EU (2018 survey: 53% of Brits think the EU has been a force for good)

Brexit terminology explained: EEA/EFTA, non-tariff barriers, max fac, backstop, etc. Part of a huge reference resource

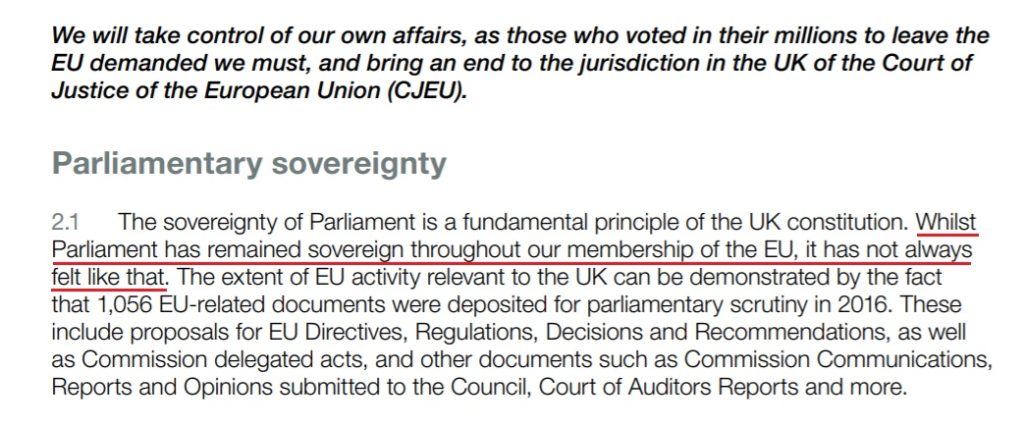

Full Fact: What proportion of UK laws are written by the EU (of which, just to remind you, the UK is a contributing member)? Answer: smaller than you think. There’s a ton more EU mythbusting on the same site.

Financial Times: How EU membership has benefited Britain

The referendum

Summary of Britain’s 1975 referendum on EEC membership (pdf)

The Electoral Commission’s regional breakdown of results, plus lots of other useful links

Handy summary of the known criminality associated with the referendum campaign

European Law Monitor: did people really fall for Leave’s lies? All that matters is, enough of them did. (Leave campaign literature and post-ref polling information)

Was the press coverage during the campaign balanced? – Reuters Institute. Have a guess. (Oh, and guess what percentage of spokespeople cited were experts? A staggering 13%.)

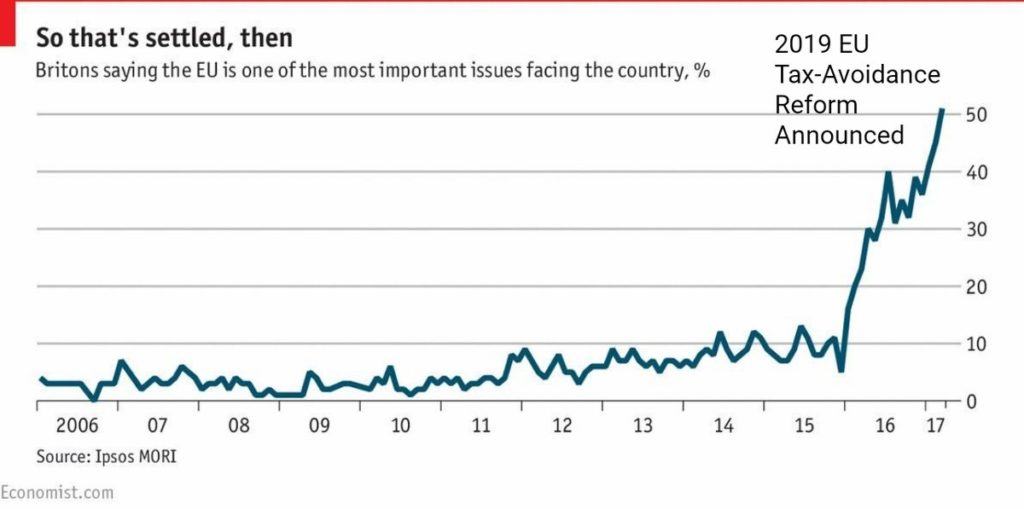

A staggering graph plotting the results of the annual survey that asks people: “What’s the most important issue facing Britain?” Look at the blue line. Just fucking look at it.

The BBC’s EU referendum poll tracker. Pay particular attention to the “don’t knows”. Somehow, in the last few days of the campaign, someone managed to swing all the don’t knows to Leave. It’s surely a complete coincidence that Vote Leave spent the vast majority of its (illegally large) budget on unaccountable, bespoke social media adverts in the last three days.

Economics and trade

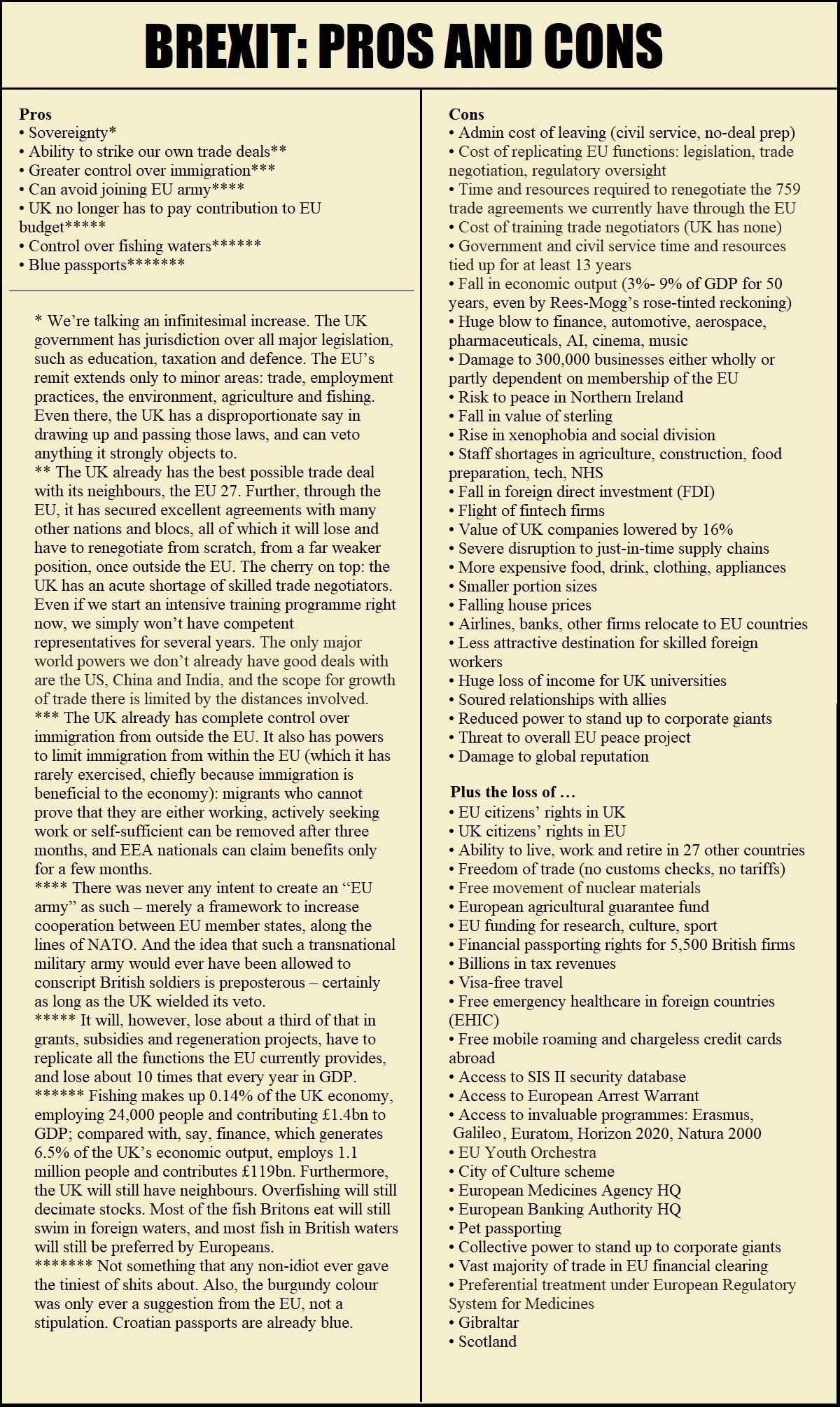

The UK government’s analysis of the long-term economic impact of Brexit

The UK government report (pdf) on the impact of no-deal Brexit

The Brexit Shitstorm Forecast, a rolling summary of the effects, good and bad, of Brexit. (Almost three years, and nothing good yet)

Bloomberg’s Brexit Tracker, listing all the effects, negative and negative, of Brexit on UK businesses

Treasure trove of Brexit-related info from IGD, a research group affiliated with the food and grocery industry

Brexit job losses: no further explanation needed

Steve Peers debunks the “batshit” Lisbon Treaty 2022 myths

Steve Analyst’s thread on EU coffee tariffs (refuting a tiresomely common Brexit lie)

Jim Cornelius’s thread on EU tariffs on oranges (same deal)

Jim pulverises animatronic turnip Tim Martin’s bullshit about tariffs on rice

Holger Hestermayer’s thread on GATT article XXIV: can trade continue unhindered after a no-deal Brexit? No.

Thread by Edwin Hayward: what does trading on WTO terms really mean?

Institute for Government: 10 things to know about WTO

So you thought Brexit was going to help the fishermen?

Kid Tempo’s thread on why unilaterally dropping all tariffs isn’t the magic bullet for the UK’s trade woes.

All the times Brexiters promised we’d stay in the single market (video). Actually, there are many more, but this was all they’d turned up on video at the time.

Immigration and freedom of movement

My potted history of human migration

Me on myths about freedom of movement

The 3 Million: useful info for our European friends and our former compatriots

Northern Ireland

Jonathan Mills’s thread on the Northern Irish backstop

Higher education

Universities UK: The impact of Brexit on the sector

Britain’s global influence

UK government report on the effects of Brexit on the UK’s role in the world

Fake thinktanks, data harvesting and targeted propaganda

Richard Corbett’s Long List of Leave Lies lists the fibs the Leave campaign told in order to cheat their way to victory, along with some impressive refutations

European Commission’s Euromyths: hundreds more examples of the above, generally peddled by the UK’s gutter press

The Bad Boys of Brexit: MEP Molly Scott Cato’s treasure trove of background info on the people who engineered the disaster: a cabal of chancers, shysters, hucksters and outright villains

How much your average Tory MP knows about the EU

Who are the European Research Group?

Banks and Wigmore give evidence to the DCMS committee (then walk out early) (video)

Open Democracy: How did Arron Banks afford Brexit?

Andrew Tyrie questions Vote Leave chief Dominic Cummings on the referendum, Jun 2016 (video)

Cummings’s blog posts on the referendum (content warning: tedious, smug and overwrought, but some enlightening nuggets buried in there somewhere)

We need to talk about Tufton Street: Details of the shadowy network of opaquely funded “thinkthanks” based at 55 Tufton Street – the Institute for Economic Affairs, Civitas, the Taxpayers’ Alliance et al – whose representatives, despite their complete lack of relevant qualifications and clear neoconservative agenda, are interviewed on political talkshows as “independent experts” on a daily basis

George Monbiot on how US billionaires are funding the far right in the US and UK

Why do American corporations want Brexit so badly? Read this 2014 essay on the Heritage Foundation website to find out. (Heritage is the US template upon which the UK “thinktanks” were built: climate change sceptics, anti-tax, anti-regulation, inexplicable charitable status, donors unknown – but agenda points squarely to big business)

The Koch brothers’ integrated strategy for social transformation. Sounds terrifying, doesn’t it? It is.

Robert Mercer, the shadowy, evil billionaire behind Breitbart and Bannon

The Brink: inside Steve Bannon’s plan to ruin the world

Who is Chloe Westley? Short thread (with some interesting addenda) on the TaxPayers’ Alliance’s Australian rentagob shill

Gavin Esler for the New European on the lesser-known faces of the Brexit Posse

Electoral Commission findings on breaches of law by Vote Leave and BeLeave’s Darren Grimes

DeSmog: Economists for Free Trade: the climate change deniers pushing for a hard Brexit

Carole Cadwalladr’s Observer piece on the global data operation that drove Brexit, still one of the few efforts by mainstream media to get to grips with the problem

What is 4chan, and what role did it play in the rise of Trump and the alt-right?

VICS (Voter Intention Collection System): the software Vote Leave used to win

DFR Labs: How bots work

Andrew Hickey: Why people can’t think – an essay on the increasingly obvious limitations of the human brain

Dr Emma Briant’s testimony to the DCMS on the murky methods of Cambridge Analytica, AIQ et al (pdf)

How Trump uses the same methods as Hitler (audio: interview with founder of SCL Group, parent of Cambridge Analytica/AIQ)

Sara Danner Dukic’s thread on how they fuck with your brain

Umair Haque’s essay on how social media hacked the human mind

Telegraph: two-thirds of Britons polled in May 2016 did not think Brexit would make them any poorer. Boy, how stupid must they feel now?

Who funds the anti-NHS “thinktank” the Institute for Economic Affairs? Well, blow me down if it isn’t Big Tobacco.

The Russia connection

The Atlantic Council’s reports on Russian disinformation efforts in Europe: 1.0 (UK, France, Germany), 2.0 (Greece, Italy, Spain) and 3.0 (Denmark, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden)

The Russian “Firehose of Falsehood” (pdf) model of propaganda

NPR: What is dezinformatsiya, and how does it work?

JJ Patrick’s Pfft-what-tinfoil-hat-bollocks-oh-no-it’s-suddenly-all-terrifyingly-true Alternative War, on the kleptocrat/populist disinformation masterplan. That’s a link to the Amazon page; there’s a good taster here

Daily Beast: Russia’s long history of messing with American minds

US Helsinki Commission on Russian information warfare

Washington Post: how the trolls invaded America (not Brexit, but related)

Fake news and social media

The Department of Culture, Media and Sport’s 2019 report into fake news (pdf)

Government preparations

Hansard: the Brexit statutory instruments

Online debate: populist tricks

My bit on feeble populist arguments and how to rebut them. Basically, how to shoot down those dreary, witless souls who parrot slogans they’ve picked up from memes and the Daily Express – “They need us more than we need them”, “Millennium bug!” – but don’t really understand.

How to outthink a Brexiter (no, it doesn’t just say, “Think”)

The turning tide

Swansea has second thoughts about Brexit

On Twitter? Follow @RemainerNow, the community for those who are kicking themselves.

And just for shits and giggles …

Daniel Hannan’s hilarious flag-waving vision of Britain after Brexit. Be sure not to have a mouth full of tea when you read.

Do also check out the Brexit database and aggregator, a rather more thorough, if less colourful approach to the same sorta ting.

Work in progress – more to follow …