Laziness, envy and fear: the handmaidens of Brexit

Fearful people want swift, simple solutions – and woe betide any pointy-headed intellectual who gets in the way with pleas for calm or evidence

Over the last two years, there have been more attempted explanations of Brexit and Trump than there have been leaders of Ukip. It was racism; it was the Russians; it was a longing for simpler times; the dumbing-down of culture; the echo chambers of social media; a collective brain fart. And all those things doubtless played a part.

But since it’s the alarming new wave of anti-intellectualism – the collapse of faith in expertise – that has enabled both these developments, it might be productive to consider how we’ve suddenly arrived in a world where knowledge is seen as a shortcoming and “I’m no expert” is practically a boast.

History tells us that surges in populism like the one we’re experiencing generally follow periods of economic strife. But while times may be tough by modern standards, our privations are nothing next to the hardship of the 1930s, 50s, or even the 70s (yet). Cashflow can’t be the sole cause.

I’ve already written about the evolution of language and culture to paint an ever darker picture of intellectuals; but as I said, those are as much symptoms as causes of the new climate.

Why, at an individual level, did people vote for Brexit and Trump? What have intellectuals and liberals done to deserve the sudden scorn of the masses? To my mind, there are three main factors.

Envy

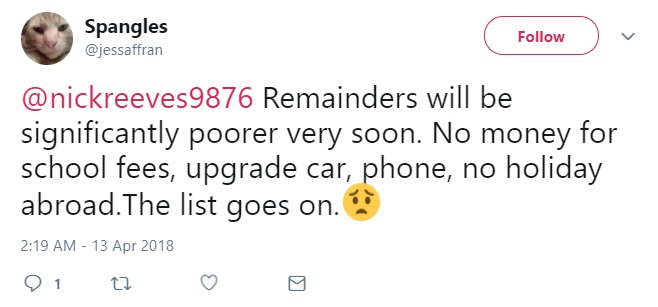

It’s hard to escape the feeling that some of the people who voted for Brexit and Trump did so out of sheer spite. Having not, perhaps, achieved the station in life they feel they deserve, they are beside themselves at the notion that others might have found relative happiness. Their pain is all the more acute for being at least partly self-inflicted. They’re haunted by the suspicion that if, at school, instead of flicking bogies at the ginger kid who finished top in the spelling test, they had applied themselves, or if, in their first grown-up job, they’d thrown sickies less than once a fortnight, they too might have finished a little higher up the field.

Others’ grievances have a little more substance. After all, the world is plainly full of high-flyers who haven’t earned their wings. Too many people have got where they are by cheating, or through nepotism, the old boys’ network, or dumb luck. And those who have put in the graft are often rewarded out of all proportion with their efforts. I’m sure running Lloyds Bank is no cakewalk, but is António Horta Osório’s contribution really worth £8m a year? Mark Zuckerberg may have sweated blood building Facebook, and his social network brings pleasure to millions (when not furiously fucking them in the arse), but is $65bn really a commensurate prize when talented, dedicated nurses and firefighters are topping up their weekly shop at the food bank?

We’ve reached a point where the top dogs have a bigger share of the Winalot than ever before. What’s more, the inequality has never been more glaring: it’s rubbed in our faces daily on reality TV shows, newspaper and magazine front pages, advertising billboards and Instagram.

But the perception that all people keeping their heads above water are similarly undeserving is grossly unfair to those who started without any advantage – and particularly so to intellectuals, such as writers and academics, who on the whole have it a lot less cushy than is widely believed.

Laziness

“Nothing has more retarded the advancement of learning than the disposition of vulgar minds to ridicule and vilify what they cannot comprehend” – Samuel Johnson

Far too many Britons – and I include Remain voters here – voted in the EU referendum in ignorance. I’m constantly astonished at the number of people with a tenuous grasp of the issues involved, even almost two years after the decision. The majority seem to have voted with heart rather than head, without taking the time to find out if there was any truth to the tabloid stories about Brussels bureaucracy, or how deeply integrated the UK’s economy is with the EU. I don’t think some of them even read the fucking bus.

There are a couple of reasons for this. First, I don’t think many people really believed their vote would count. Both sides were expecting a walkover for Remain (so much so that many plumped for the “Give Cameron a bloody nose” option, believing that it wouldn’t tip the balance). Why bother doing your homework when your vote won’t matter anyway?

Second, many people are not accustomed – or can’t be bothered – to take in complex information. They’ve got more important, or more interesting things to think about than what James Thurber called the “clanguorous, complicated fact”. Going through the minutiae is someone else’s job.

Indeed, that’s exactly how things work in a representative democracy, our usual system of government. Since we don’t have the time to do all the research required, we elect councillors and mayors and MPs, who then, with the help of expert advisors (we hope), make decisions on our behalf. But when it comes to referendums – the purest, most direct form of democracy – those crutches fall away. You’re the expert now. At least, you should be.

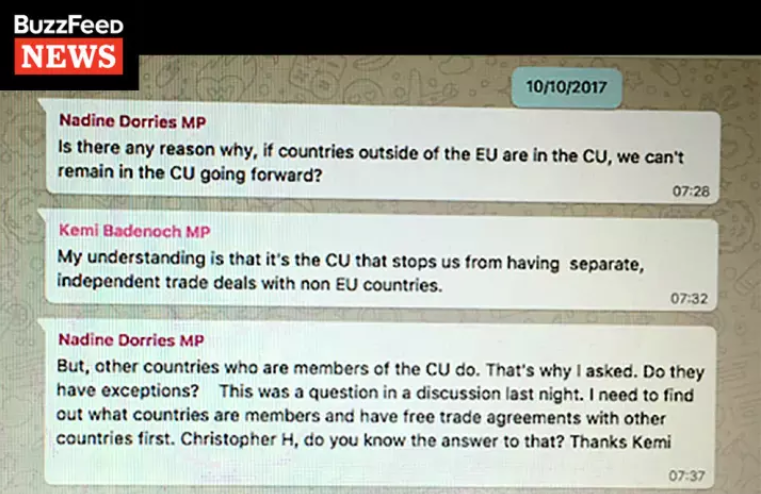

What’s more worrying is that some of the representatives we elect to make decisions for us think exactly the same way.

Nadine Dorries (MP!) came in for a lot of stick for her assertion that the vote to leave the EU was correct because international trade was too complex for her to understand, but she deserved it all and more. This is one of our supposed leaders, giving up on a matter of paramount importance just because it made her head hurt. If we all followed Dorries’ logic, humankind would have given up long ago on space flight, curing polio, powering our homes, building viaducts, developing antibiotics, compiling the English dictionary and mapping the globe.

Nadine Dorries (MP!) came in for a lot of stick for her assertion that the vote to leave the EU was correct because international trade was too complex for her to understand, but she deserved it all and more. This is one of our supposed leaders, giving up on a matter of paramount importance just because it made her head hurt. If we all followed Dorries’ logic, humankind would have given up long ago on space flight, curing polio, powering our homes, building viaducts, developing antibiotics, compiling the English dictionary and mapping the globe.

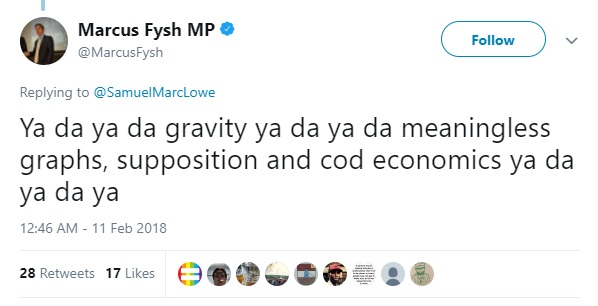

A few months later, another Tory MP made a similarly unedifying contribution to the public debate.

To label this behaviour “stupidity” is to give Dorries and Fysh too much credit. What they are guilty of here is intellectual laziness; they’re not too dumb to understand international trade. They just can’t be arsed.

This pattern is repeated thousands of times a day, in pubs, in the comments under online news articles, and on social media. Attempt to explain a point in any detail at all and you’re greeted with a “Yawn”. Boring. Tell me something simple that makes my tummy feel fuzzy instead, like how all Muslims are paedophiles.

It’s hard to pin down what’s turning us all into Homer Simpson, but there’s little doubt that in this era of tweets and vines and all-round instant gratification, attention spans and patience are declining. In 1982, 57% of US citizens had read at least one novel, play or poem in the previous year. By 2015, that had fallen to 43%. In the UK, only 40% of children now read beyond what they are obliged to at school.

Probably the scariest study in this area was carried out by Kiku Adatto of Harvard University. She found that in 1968, the average quotation from a presidential candidate used in TV news lasted 42.3 seconds; by 1988, the duration had fallen to 9.8 seconds. In 2000, according to a later paper, it stood at 7.8 seconds. Donald Trump’s rousing battle cries – “Make America great again”, “Build the wall”, “Lock her up”, “Drain the swamp” – come in at an average of 1.3. You can’t solve complex problems like crime and unemployment and terrorism with 1.3-second soundbites. But people, it seems, aren’t willing to listen for any longer.

(I’ll go into this in more detail in my next post. If you want to do some prep in advance, I recommend that you go out and buy Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking Fast And Slow. Even if you don’t intend to read the next post, you won’t regret it.)

Fear

Four years before the referendum, no one, beyond a handful of cryogenically frozen Tories and fanatical racists, cared much either way about the UK’s membership of the EU, probably because it had no readily measurable effect on their everyday lives. In a survey carried out at the end of 2012, just 2% of respondents said the EU and Europe were the most important issues facing Britain. But by June 2016, millions of people had suddenly become raving Europhobes. What happened?

The last great wave of populism in the 1950s occurred at a time of unprecedented flux. Millions had lost loved ones in the second world war, food and money were scarce, and the world was cowering under the threat of nuclear armageddon. Technology was advancing at a dizzying pace: newfangled gadgets from TVs to phones, from freezers to food mixers, transformed homes beyond recognition in a matter of years. Cultural change was not lagging far behind, thanks to contraception, vaccination, postwar immigration, and the more prominent role in public life played by women.

For many people, change engenders fear. We prefer to stick to familiar things and routines because they don’t require mental effort and we know from experience that they won’t kill us. Too much innovation too fast sends their primal instincts into overdrive. The calmer, more rational part of the brain is cut off. They want swift and simple solutions to their problems, and woe betide any “pointy-headed professors” who get in their way with pleas for calm or evidence.

Change-induced fear, I believe, was also a decisive factor in 2016. Immigration, sexual liberation, WhatsApp, gay marriage, wind farms, Amazon, contactless payments, self-driving cars: the scale and pace of innovation can be bewildering even to young, plastic minds.

Few of these things, however, are threatening in and of themselves. On a day-to-day basis, most of them can be mastered, or avoided, easily enough. But the crucial point here is not the change itself; it’s the perception of change.

Each and every one of the Remain camp’s warnings about the likely dangers of leaving the EU was airily dismissed with a cry of “Project Fear!”. But the other side was even more adept at peddling dread. “Turkey is joining the EU!”; “The EU is becoming a superstate!”; “The EU wants to form an army!”; “The EU’s share of world trade is shrinking”.

After 30 years of relentless Brussels-bashing by the tabloids, the Vote Leave campaign, with the forensic assistance of psyops firm Cambridge Analytica, weighed in with a bumper anthology of horror stories. Online, an army of trolls sputtered out every tale they could find, true or false, about terrorists and feminists and Muslim rape gangs and fucking Easter eggs. While the streets were notable for the absence of upheaval, the gutter press and gutter politicians successfully forged the narrative that the British and American ways of life – and particularly the white male way of life – were under immediate threat. To deliver their message more effectively, they used deliberately emotive language: when the likes of Katie Hopkins deploys the words “swamped”, “infestation” and “cockroaches”, she does so knowing full well which part of the brain she is poking at.

Those who did not take the time, or did not possess the critical faculties, to question what they read went into fight-or-flight mode. Few could point to any direct personal experience of the danger posed by immigrants or the European Union or Barack Obama, but they had been told that they were a threat. The papers said so. My friend on Facebook shared a meme saying so. Simple, swift solutions.

And so they gobbled up the vacuous, undeliverable slogans. And they voted for Brexit and Trump.

I have a couple more things to say about this, and then I’m going to take a bit of a break and write a hit romcom and retire to fucking Lanzarote. Brexit permitting.