The western world is some way from being a technocracy. But there is no doubt in my mind that those sectors that are run on the basis of expertise – the judiciary, the civil service, academia, the creative sector – are under ferocious attack.

Intellectuals, however, are no pushovers, because – well, they’re bright, and they usually hold influence and power. When ideologues face experts on a level playing field, they tend to have their arses handed to them – see the epic owning of alt-right bilemonger Paul Joseph Watson by teacher Mike Stuchbery over the question of racial diversity in Roman Britain. So if a fair fight is out, how is this war being prosecuted?

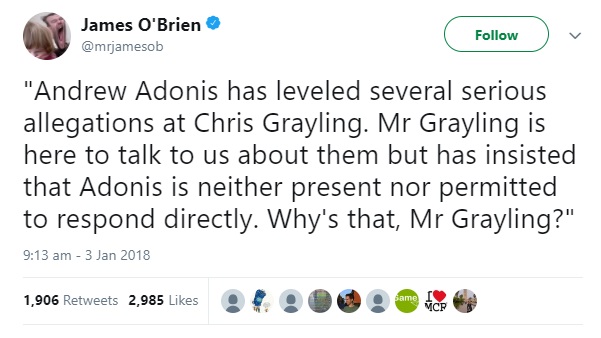

Wherever possible, extreme rightwingers steer clear of direct confrontations. Jeremy Hunt declines Ralf Little’s offer of a live debate about mental health provision; Chris Grayling refuses to appear on a radio chat show with Andrew Adonis.

They’re assisted in this by the dumbed-down clickbait culture that’s consuming our media. The coverage of science in most newspapers these days is woeful: research findings are published without caveat, rebuttals added too late, if at all. And on news programmes, it’s increasingly rare to see a genuine expert consulted on any issue of note. You can understand why: academics can be a little dry and stuffy, their arguments detailed, nuanced, full of ifs and buts.

They’re assisted in this by the dumbed-down clickbait culture that’s consuming our media. The coverage of science in most newspapers these days is woeful: research findings are published without caveat, rebuttals added too late, if at all. And on news programmes, it’s increasingly rare to see a genuine expert consulted on any issue of note. You can understand why: academics can be a little dry and stuffy, their arguments detailed, nuanced, full of ifs and buts.

Watch the BBC or Sky next time there’s a debate about gun control: guaranteed, there’ll be someone from the NRA, spouting the usual inflammatory bilge, and as a counterpoint, if you’re lucky, you might get the relative of a shooting victim. They don’t want people who know about guns; they want people who care about guns (and who generally add little of substance to the debate). Similarly, in any discussion about the EU, do the producers summon a professor of European history or an economics journalist? Good God no, haul in a rabid Remainer and a batshit Brexiter and watch the sparks fly!

This sidelining of rational voices is even easier on Twitter, where Brexiters can obliterate all those who post inconvenient truths with a tap of the block button.

If a showdown with someone who knows their stuff is unavoidable, far right-demagogues have several ploys. The crassest is simply to prevent their opponent from getting a word in edgeways, as Nigel Farage did to Femi Oluwole on his LBC show, and Julia Hartley-Brewer to Heidi Alexander on Talk Radio. It seems the freedom of speech they profess to hold so dear only matters when it’s theirs.

If a showdown with someone who knows their stuff is unavoidable, far right-demagogues have several ploys. The crassest is simply to prevent their opponent from getting a word in edgeways, as Nigel Farage did to Femi Oluwole on his LBC show, and Julia Hartley-Brewer to Heidi Alexander on Talk Radio. It seems the freedom of speech they profess to hold so dear only matters when it’s theirs.

Another part of their arsenal is the logical fallacy. I don’t want to regurgitate my entire post on the subject here, but to recap, they’re non-arguments masquerading as arguments – underhanded attempts to deflect or reframe the debate, or throw the opponent off balance, rather than address the topic at hand. The ones you’ll come across the most are the argumentum ad populum (“17.4 million people can’t be wrong”), the false dichotomy (“You’re either for freedom of speech or against it”), the appeal to emotion (any tweet by Daniel Hannan), tu quoque or whataboutery (“But Hillary’s emails”), tone policing (“Typical condescending Remoaner”), and Boris Johnson’s favourite toy, the straw man (“So what you’re saying is …”).

But the populist’s standard-issue weapon is the ad hominem: the personal attack. Play the man and not the ball, and hopefully you can forget about the ball.

I’ve written before, too, about the revival of the art of the smear. Essentially, Leave and Trump advocates, like fascists throughout history, love to sling mud. In logic speak, this is known as poisoning the well: an attempt to discredit the target such that people will no longer believe or trust them. Thus, no matter how wise their words today, Tony Blair (Iraq), Nick Clegg (tuition fees), Tim Farron (homophobia), Hillary Clinton (crooked, although no one has yet produced any evidence to support this assertion) and Jeremy Corbyn (IRA, Palestine) can, in some eyes, never be taken seriously again.

(The reason ad hominem works, of course, is that it is not entirely without foundation. Some people or publications are habitual liars or fools and, if shown to have been so often enough, probably should be ignored. Into this category fall most of the UK tabloids, Fox News, Hannan and many of his Brexit conspirators, and most of the alt-right – but also plenty on the far left. Generally speaking, however, people should not be permanently written off on the basis of one or two lapses of judgment.)

Intellectuals – and for the purposes of this section we can scale right down to passably intelligent liberals debating on Twitter – represent a particular challenge for the ad hominist. They don’t tend to be well-known, so their every past mistake and foible is not in the public domain. Populists will still take every opportunity to play the man rather than his argument, but where that’s made difficult (eg by the anonymity conferred by the internet), they’ll go after his sources, or his motives, instead. And in my experience, they tend to do so in one of six ways.

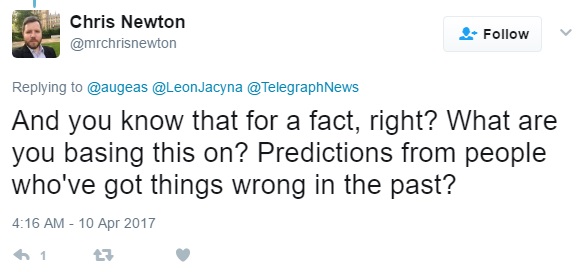

1) Fallible

You may have more information than me, but you were wrong once before, so you may be wrong now.

The argument that someone’s opinion shouldn’t be trusted because she doesn’t have a 100% record in her field is idiotic, but it’s one that’s trotted out with tiresome regularity, most often, in the context of Brexit, in respect of economists.

Yes, they goofed up once. (Or rather, a different group of economists did; that was 10 years ago.) But those economists were appointed to their jobs over thousands of hugely qualified rivals. If they weren’t generally good at their jobs, they’d have lost them long ago. They’re still far more likely to make accurate forecasts about the UK’s future outside the EU than Kev from Castle Point.

Yes, they goofed up once. (Or rather, a different group of economists did; that was 10 years ago.) But those economists were appointed to their jobs over thousands of hugely qualified rivals. If they weren’t generally good at their jobs, they’d have lost them long ago. They’re still far more likely to make accurate forecasts about the UK’s future outside the EU than Kev from Castle Point.

Say you find out the cardiac surgeon who’s going to perform open-heart surgery on you lost his last patient. Would you rather he operated on you, or a bricklayer? Someone’s past failings have no bearing on the credibility of their statement today.

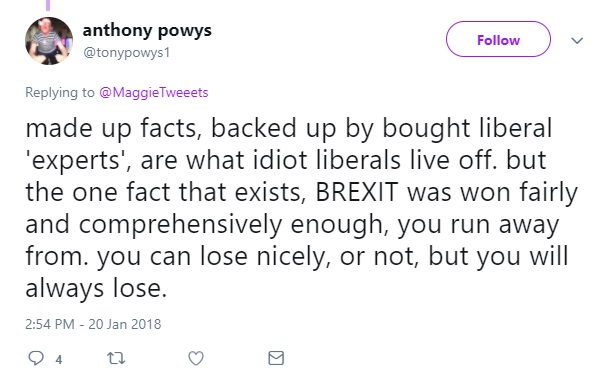

2) Biased!

You may have information, but that information comes from a compromised source.

The word “biased” is tossed around by arch-Brexiters almost as freely as “democracy” and “Get over it”, and yet it’s far from clear whether they know what it means.

Bias is not a synonym for preference. You can prefer something to something else instinctively, or having considered both options carefully. “Bias” specifically means a predisposition to like or dislike something because you have a stake in the matter. I’m not biased against wasps; I’ve just weighed up the pros and cons of wasps and concluded, as I imagine most have, that they are a bad thing. If I argue that 1 + 1 = 2 and you argue that 1 + 1 = 3, I’m not biased towards the result 2. I’m just right.

Similarly, I don’t have a holiday home in Florence and I don’t have a crush on my Latvian barista. I have no vested interest in the future of the EU. I’ve just researched the issue, calculated the likely fortunes of my country within and without it, and decided, overwhelmingly, that within is better.

More commonly, this accusation is levelled at any source you use to back up your claims. There’s more justification for this – after all, the Mail, Express, the Canary, and fake news sites like Westmonster, Breitbart and Infowars are notorious for their partisan views and casual relationship with the truth. But a number of other news providers – the “mainstream media” – are also regularly rubbished.

There’s a lot of contempt for the Guardian, for example (mostly from people who haven’t opened it since 1981). Sure, it probably has more commentators from the left of the political landscape than the right, although most are tepidly centrist these days. But it provides a forum for voices from across the spectrum. It follows due journalistic process: it names its sources where possible, and allows those mentioned in its stories a right of reply. It has subeditors and lawyers and its staff routinely discuss the most balanced way to word headlines. On the whole, it uses neutral language in its news pieces, with minimal value judgments. It keeps its news reports separate from its opinion pieces. And above all, it is accountable to its readership, to its own ombudsman, and to the wider public. It responds to all complaints, and when it is incorrect, it publishes retractions and apologies.

The likes of Infowars, Fox News and the Express, meanwhile, are bound by no such constraints. They publish only stories that promote their narrow, ultra-right conservative agenda. News and opinion are an inseparable morass: their stories tell you not just what happened, but exactly what you should think about it.

Crucially, the established free press doesn’t routinely make shit up. Yes, it makes mistakes, and yes, it has been known to put a mild spin on things; but it doesn’t falsify footage, invent quotes, misidentify pictures, or blatantly publish provable falsehoods.

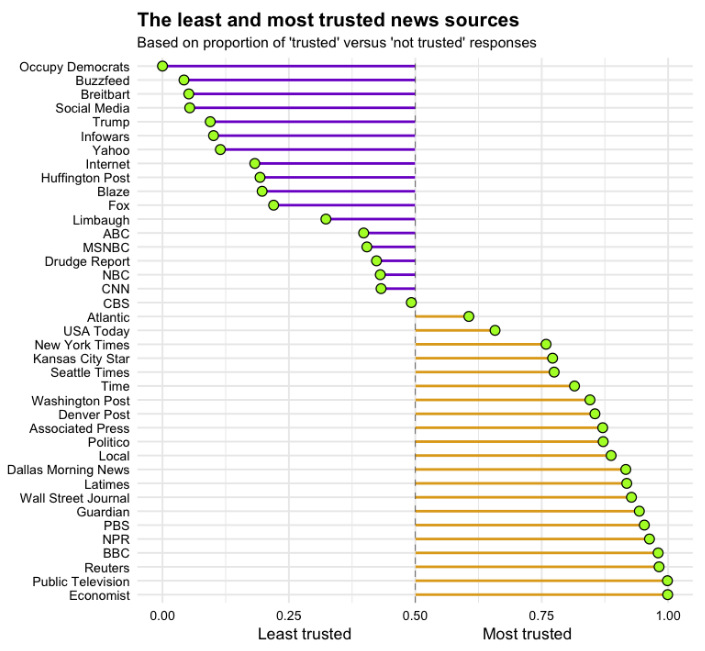

So next time someone plays the “MSM” card, stand your ground. Ask them: “What’s that got to do with anything? The BBC/Guardian is the fourth/seventh most trusted news source in America. (Fox News is 29th.) Which specific details of the report I linked to are wrong?”

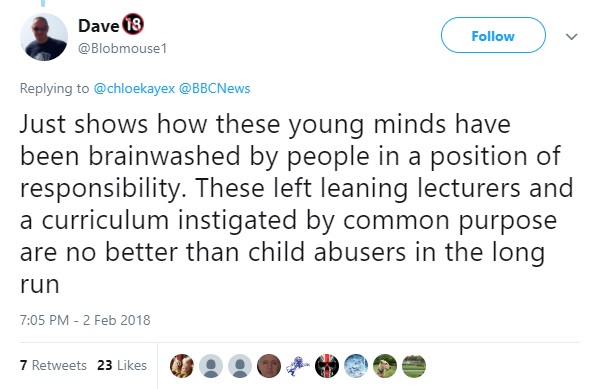

3) Brainwashed!

Yes, you have more information than me, but it is false information imparted to you by another. You are a dupe; a stooge.

I love it when Brexiters pull the pin on this one. “You’ve been brainwashed into loving the EU.” As if, through some preposterous sequence of accidents, I had only ever been exposed to pro-EU messages. And it really would have to be preposterous: most of the tabloids (and the Telegraph) have printed nothing but negative stories about Brussels for decades; the quality papers, meanwhile, never said much positive about it because – well, come on, European politics. (If the EU really is a dictatorship, it must surely go down as the dullest in history.)

The circulations of the Guardian and Independent, the only unabashedly pro-EU papers left, are, as the right never tires of pointing out, dwindling rapidly. Personally, I can barely recall coming across any positive messages about the EU, even from the Remain campaign during the referendum. Am I missing something? Euro-conversion booths on our high streets, perhaps? The only real advertisement I ever saw for the EU (before I went looking for information) were EU citizens themselves – valued contributors to our economy and our culture, to whom I cannot apologise enough for the shitstorm Brexit has visited upon them – and the general impression that the country was more prosperous and culturally rich than when I was a boy.

Perhaps sensing the absurdity of that argument, some Brexiters shift the blame to an institution that, to them, is shrouded in mystery: university. Our places of higher learning, some seem to believe, are hotbeds of communism, cranking out rows of malodorous, long-haired men and short-haired women who love immigrants and homosexuals and quinoa and hate white people and Britain and America.

If any of these deluded souls had ever been within a country mile of a campus, they’d know the truth was more mundane. With the exception of the politics faculty and the student union offices, universities are not especially political places. Some right-on loon might make the news every few weeks with a call to ban music from campus because it’s discriminatory against deaf people, but most courses don’t even touch on politics (students of history and the social sciences make up 8% of the corpus) and membership of political groups is low. Most students aged 18-21, like most non-students aged 18-21, are more interested in beer, sport and sex than they are in social welfare budgets or the privatisation of the Land Registry.

If any of these deluded souls had ever been within a country mile of a campus, they’d know the truth was more mundane. With the exception of the politics faculty and the student union offices, universities are not especially political places. Some right-on loon might make the news every few weeks with a call to ban music from campus because it’s discriminatory against deaf people, but most courses don’t even touch on politics (students of history and the social sciences make up 8% of the corpus) and membership of political groups is low. Most students aged 18-21, like most non-students aged 18-21, are more interested in beer, sport and sex than they are in social welfare budgets or the privatisation of the Land Registry.

Besides, how the hell is this monumental operation being conducted? Are there posters on every wall depicting a smiling Jean-Claude Juncker with the slogan, “Your country needs EU?” Is Ode To Joy piped into student halls of residence while they sleep? Are the student union canteen lunches laced with brie?

If there were some sort of conspiracy to indoctrinate western students in leftist ideas, you’d think someone would have produced some definitive proof. But 49% of Britain’s young people go into higher education. That’s half a million people a year. Surely one of them – or a rogue lecturer, or cleaner – would have recorded some footage on their mobile by now?

There’s a far simpler explanation for young people’s attachment to the EU: their minds are more idealistic, more plastic, more open to new ideas. In addition, university teaches them to think critically, and introduces them to people from a far more diverse range of backgrounds than they were exposed to at home. It’s not the current education system that makes people liberal; it is education itself.

And ask yourself this. Who is more susceptible to brainwashing: the person with at least three years’ extra education, who has been trained to question and critique everything she reads; or the person who never once raised his hand in 10 years of school?

4) Bribed!

You may have information, but it is information that you have been paid to disseminate.

We’re fully into wackjob territory now. I know George Soros is rich, but to fund every Remain vote and leaflet and march and pro-Remain MP and academic and research paper and CEO and judge and economist, and keep it all a secret … You know what? If that did turn out to be the case, I’d remain a Remainer, because I’d want to be on that man’s side.

We’re fully into wackjob territory now. I know George Soros is rich, but to fund every Remain vote and leaflet and march and pro-Remain MP and academic and research paper and CEO and judge and economist, and keep it all a secret … You know what? If that did turn out to be the case, I’d remain a Remainer, because I’d want to be on that man’s side.

5) Brideshead

You may have information, but it is esoteric information, irrelevant to everyday life.

Alongside the soap-dodging, sickle-wielding snowflake, another university stereotype stubbornly persists: of Rupert and Sebastian, foppish, entitled aristocrats lounging louchely in their double set while Mrs Miggins meekly serves them tiffin and opium. Entitled, effeminate, with alabaster hands that have never been in the same room as a screwdriver, they can solve complex equations or recite passages of poetry or critique Leibniz’s theory of monads, but when it comes to the business of getting by in life, they’re all at sea. And yet, on graduation, Daddy will fix them up with a cushy number in the civil service or on the board of a big bank.

This, I think, is the image the tabloids are trying to conjure up when they use phrases like “out of touch” and “elite” (the American equivalent seems to be “coastal elite”). They’re trying to foster this idea that students (and academics, judges, civil servants, and anyone else who may have touched a book by someone other than Danielle Steel or Andy McNab) are sheltered from hard reality and therefore unqualified to speak on real-world issues.

Loath as I am to break the devastating news to you, Brexit fans, things have moved on a lick since the 1930s. Ninety per cent of UK students are now from state schools. Daddy’s more likely to be a bookie than a landed gent. And contrary to your belief, the laws of the universe apply as much at university as they do in the “real world”. You still have to work hard, you still have to pay your way – most undergraduates now do regular temporary work on top of their full-time course – and the social competition from your peers is, if anything, more intense. All that, plus the crushing spectre of tens of thousands of pounds of debt hanging over you, and no guarantee of a job at the end of it. Small wonder that suicides among students have doubled in the last decade.

A greater number of students than ever are studying hard vocational subjects, in science, IT, agriculture and journalism, with clearly defined careers at the end of them. In any case, education isn’t about what you learn. It’s about how you learn, how to develop a curiosity about the world, how to question and understand and predict and follow chains of logic.

Besides, if people are so implacably opposed to a pampered, nepotistic elite, they’ve chosen a decidedly odd bunch of champions to rid themselves of the scourge. Jacob Rees-Mogg (Eton and Oxford), Daniel Hannan (Marlborough and Oxford) and Boris Johnson (Eton and Oxford); and in the US, Donald Trump (wealthy businessman), Steve Bannon (Goldman Sachs financier and media executive) and Reince Priebus (corporate lawyer).

6) Boring!/Bollocks!/Bullshit!

You may have information, but it is … bollocks. Because I say so.

Probably the most common responses from Brexit fanatics to any point I make, or any post I write, are one-word answers: “Rubbish”, “Nonsense”, “Bullshit”, “Bollocks”. They go silent when you ask them to elaborate. I can’t begin to imagine why.

So much, then, for the strategy behind the war on intellectuals. In my next post, I’ll look at the war aims.