(Fair warning: there’s a lot of ground to cover on this subject, so this will be the first in a mini-series.)

In 415AD, a band of thugs dragged the mathematician, astronomer and Neoplatonist philosopher Hypatia from her carriage and took her to a nearby church, where they stripped her naked, battered her to death with roof tiles, dismembered her and set the body parts on fire.

During the Spanish Civil War of 1936-39, the majority of the 200,000 Spanish civilians killed were members of the intelligentsia, as were most of the victims of the “killing fields” of Cambodia in the late 1970s. In the months after the invasion of Poland that triggered the second world war, the Nazis captured and killed around 100,000 Poles, 61,000 of whom were academics, priests, lawyers and doctors, in a secret cleansing operation codenamed Intelligenzaktion.

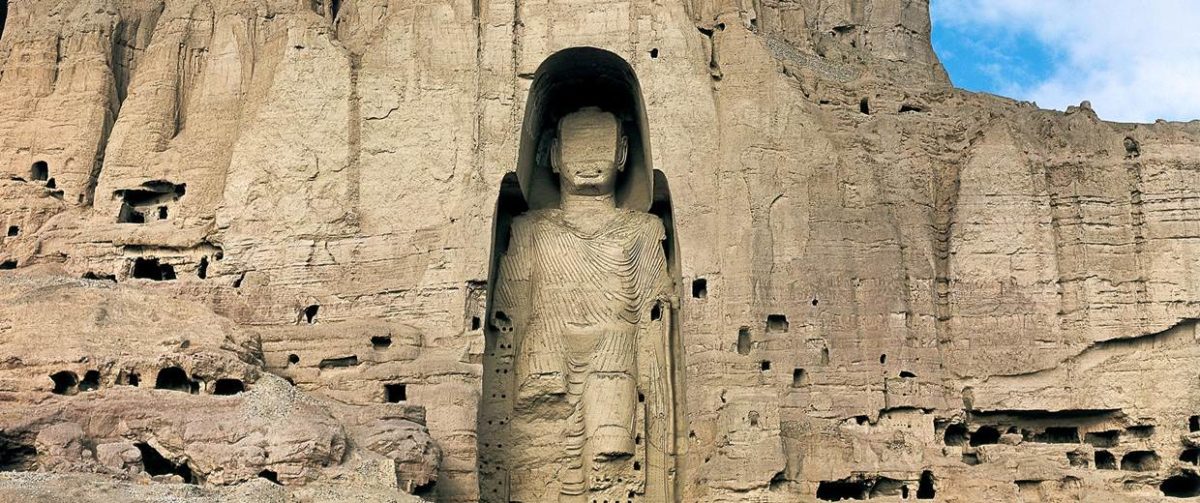

On his accession to power in Iran in 1979, the Ayatollah Khomeini closed all universities and either executed or drove out most of the country’s intellectuals. In 2001, the Taliban planted and detonated explosives to destroy the Buddhas of Bamiyan, giant sandstone sculptures in the Hazarajat region of Afghanistan dating from the 6th century.

And in a history lesson at Ridgeway School in Swindon in 1982, Gavin McCracken pulled a wad of mucus from his nostril, rolled the sticky residue into a ball, and flicked it at the back of Andy Bodle’s head after the latter raised his hand to answer the teacher’s question.

All right, so it’s not exactly the martyrdom of Hypatia, but there’s a direct line connecting 5th-century Alexandria to Gavin McCracken’s bogie. Humanity has a long and inglorious history of persecuting its brighter minds and vandalising its culture, and if the last couple of years are any guide, it’s far from done yet.

“You know, I’ve always wanted to say this – I’ve never said this before – with all the talking we all do, all of these experts, ‘Oh we need an expert’ – the experts are terrible!” – Donald Trump, Wisconsin campaign rally, April 2016

Once again it has become fashionable, particularly on the right, to call expert opinion into question, to criticise judges and academics as “out of touch”, and to prize “real men” and “common sense” over rational inquiry. Suddenly, after years of rational debate, climate change deniers are back on an equal footing with climate scientists. Michael Gove is blithely declaring that we’ve “had enough of experts”.

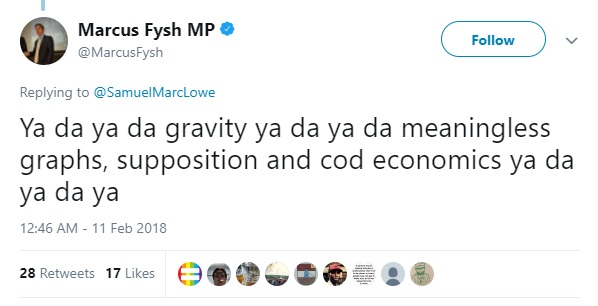

And a serving British MP thinks this is a perfectly reasonable reply to an economist on Twitter:

It seems at first sight that in the space of a few short months, someone – this is not the place to speculate as to who – has begun to shape a reality in which “overeducated” is routinely deployed as a term of abuse, in which the complexity of a trade arrangement is considered sufficient grounds for binning it, and in which the views of a West Ham fan who left school at 15 are deemed as valid as those of a politics professor at LSE.

After years of relative peace, harmony and prosperity, a good chunk of the populace suddenly seems hellbent on dragging us back to the Byzantine era. But is this really an overnight development?

In his Pulitzer-winning book Anti-Intellectualism in American Life, historian Richard Hofstadter charts the history of the relationship between his country and its intellectual class. For Hofstadter, writing in 1963, the most recent outbreak of boffin-bashing was the period of 1947-56, when the erudite Democrat Adlai Stevenson lost out twice to man-of-action Dwight Eisenhower in the presidential elections, and Joseph McCarthy’s Communist hysteria was at its vindictive height.

Hofstadter concludes that backlashes against the highly educated are cyclical, usually coming when times are economically or otherwise tough, after extended periods of liberal governance, and usually led by the church, business interests, and those on the right of the political spectrum. (I’ll be returning to Hofstadter a lot, as the parallels between what he describes and our present troubles are consistently alarming.)

Hofstadter’s focus was exclusively on the US, through the lenses of politics, business, religion and education. One area he didn’t really touch on was language, which turns out to be just as enlightening.

Insults for the intelligent have always been with us – “know-it-all”, “clever clogs”, “smart alec”, “swot” – but the end of the second world war and the start of the cold war saw a veritable deluge of new terms. “Square”, in the sense of “boringly old-fashioned or conventional person”, which soon morphed into a synonym for “swot”, is first attested in 1944. “Boffin” arrived in 1945. These were swiftly followed by “geek” (1946), “nerd” (1951), “dork” (1967), “dweeb” and “pointy-headed” (1968) and “anorak” (1984). “Egghead” seems to have been coined around 1907, but only really gained currency in the early 50s.

It’s true that some of these slurs have lost their force over time, some have been at least partially reclaimed (geek, nerd), and others (“pointy-headed”) have disappeared altogether. Nonetheless, those who once might have reached for a word to torment their diligent classmates with are now spoilt for choice.

We’re already beyond ideal blog post length, so I’ll pause here. That’s some of the background to emergence of this brave, stupid new world. In the next few posts, I’ll consider how this came about, why it came about, what the enemies of reason propose to replace it with, and whether there’s anything we can do about it.