The first thing I hear when Mathieu and Pauline welcome me into their home is an insistent buzzing-and-slushing noise. Mathieu apologises profusely and hurries to turn off the offending washing machine. Pauline shows me through to the immaculate kitchen and offers me tea: “Would you like an Englishy one? Earl Grey?”

Both French and either side of 30, Mathieu and Pauline are two of the 3 million-plus EU citizens who chose to build a life for themselves in the UK. But that life is over. In light of the Brexit vote and the events that have followed, they’ve decided, with heavy hearts, to move on.

They’re not the only ones. Net migration to the UK fell by 84,000 in the year to May 2017, according to the Home Office’s latest figures, thanks in part to the departure of large numbers of eastern Europeans. Over 300 nurses left the NMC’s register in December 2016, almost twice the number who did so in June 2016, which, combined with an unprecedented 90% drop in the number of EU nurses registering to work here, threatens an imminent staffing crisis. Universities, too, are reporting an alarming fall in applications from EU students, which will put a huge dent in their finances. Coffee chains and farmers are already complaining of problems recruiting workers. A Facebook group called Plan B, set up by a German national in February specifically for EU citizens thinking of decamping, now has more than 1,200 members.

According to immigration law experts Migrate UK, the exodus is because of the political uncertainty surrounding EU citizens’ status, and further labour shortages should be expected. Managing director Jonathan Beech says: “Until the government ends uncertainty among EU citizens by guaranteeing rights to remain in the UK after Brexit, we are likely to see a continuation of these trends, and potentially the start of a Brexit ‘brain drain’ from the UK.”

Of the people I spoke to, none could remotely be described “spongers” or “low-value” workers. These are young, healthy, skilled, taxpaying contributors to society, who speak impeccable English and are well integrated into their local communities.

Mathieu and Pauline moved here in 2012, just in time for the Olympics, not so much drawn to the UK as repelled by the culture in France. “The system is so inflexible there. There’s a lot of nepotism, racism, a pervasive culture of sexism, and there are too many strikes,” says Pauline. “In the UK, no one gives a shit that Theresa May is a woman, or that David Lammy is an MP,” adds Mathieu. “You don’t get that in France.”

“So you came here because it was more tolerant and open?” Hollow laughter ensues.

Pauline works as a contractor for the NHS, Mathieu as a software engineer, which gives them a combined salary of £75,000; that’s £11,000 tax and £7,000 national insurance that the government won’t be collecting next year. And since Pauline has undergone one minor operation and Mathieu has visited his GP twice, you could hardly call them a burden on the state.

So where have they chosen for their new start? “Canada. It’s not just Trudeau – even if it had been Stephen Harper, we’d have thought about moving there,” says Pauline. “They love immigrants in Canada,” says Mathieu. “And as English-speaking French people, we are their dream immigrants,” Pauline concludes, her eyes twinkling briefly.

Only Mathieu currently has a job lined up in Quebec, but it turns out they’ll earn more from one income there than they do from two here – their money will go further, too. “House prices! Oh my God! Our friend just bought a five-bed house there for £220K!” “The water’s free, the electricity’s very cheap, food is super-cheap, electronics … Jackpot! We might just end up thanking Brexit.”

Which brings us to the $64m question. When did they decide to up sticks, and why? “It wasn’t actually Brexit,” says Mathieu. “I was expecting it, to be honest. People are pissed off, the system is broken, inequality is growing, people don’t want to be under rightwing Angela Merkel, the problems in Greece. It’s what the government did after Brexit.”

The tone until now has been overwhelmingly of sadness, disbelief. But suddenly a tinge of anger enters Pauline’s voice. “I’m disgusted by the attitude of the Tory government. They’re using us as leverage. It’s been 11 fucking months. All that time they could have said, ‘You’re welcome to stay,’ but they didn’t. They could have condemned hate crimes, but they didn’t. They could have told Amber Rudd to shut up. They could have told the Daily Mail to shut up.”

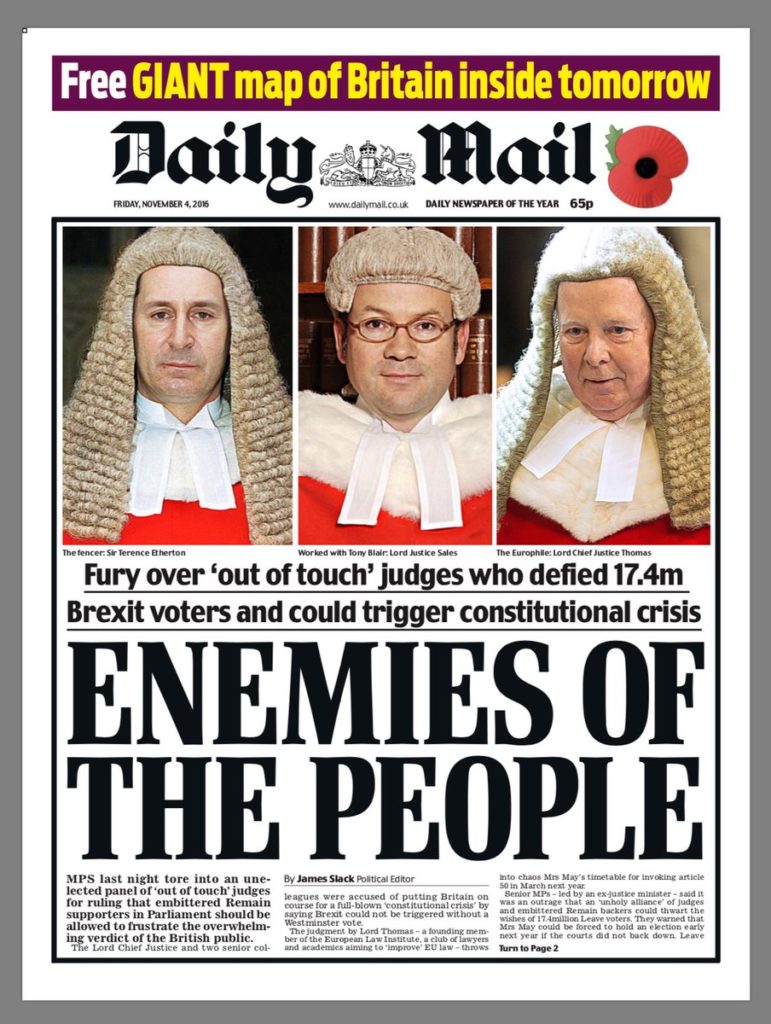

“The Daily Mail is hate speech,” Mathieu interjects. “‘Enemies of the people’? That’s Hitler, that’s literally Hitler! In France you would get prosecuted for that bullshit.”

It was the rapid poisoning of the atmosphere, they say, that made up their minds. “People tend to look on us with scorn and suspicion now,” says Pauline, “and I don’t think that’s acceptable, when you have given so much and made so much effort to integrate.

“My boss invited me into a meeting, and he said to me, ‘Brexit is good news. It’s not personal – it’s not against you – we’ve just to get rid of those Polish scroungers.”

Mathieu reserves special venom for Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage: “‘We’re going to give money to the NHS. Oh no, you know what? We lied. We’re going to stay in the EEA. No, that was all lies, too.’ And the British people don’t care. I expected people to throw eggs at Number 10, to be honest. But nothing.”

Now it seems that lying is a habit the Tories can’t shake. “‘The NHS is not failing because of cuts, it’s because the immigrants came,’ they say. ‘The housing shortage is not because we’re not building enough, it’s because the immigrants came.’”

“We’re really concerned about the British people – it breaks my heart to see so many people going to food banks, to see disabled people getting their benefits cut to nothing,” says Pauline, unprompted.

The mood has turned sombre again. “We were invited here, they needed us,” says Mathieu, “and now suddenly they are telling us that everything is our fault.”

***

The decision to leave was rather more momentous for Melissa. For one thing, she’s been here longer, having arrived from Germany in 2009. For another, she’s older – in her late 30s. Last but not least, her partner is British.

Melissa came to the UK because she loved to travel, wanted to experience a different culture, and spoke excellent English. She first set up home in Norfolk, but a year later met Sean, an automotive engineer a couple of years her senior, and when a job opportunity arose for him in the Midlands, they moved there together. She works from home as a freelance translator, earning £30,000-£40,000 a year, most of it from German clients.

The main factor in their decision to go, she says, was the work situation; carmaking is one of the areas most likely to be adversely affected by Brexit. “If the economy goes too far south, Sean might lose his job. We feel like rats leaving a sinking ship.”

But money wasn’t the only consideration. “The language being used reminds me very much of what I learned in my history lessons in Germany,” says Melissa. “‘Traitor’, ‘enemy of the state’ – it’s very worrying.

“Because I work from home, I’m not exposed to much xenophobia, but I did get a few people giving me the Hitler salute.” It’s Sean who bears the brunt of the abuse, mostly from his staunch Brexiteer colleagues. “One of them once turned round to him and said: ‘You’re sleeping with one of them, so you’re just as bad.’”

The couple’s plans to move to Germany are now at an advanced stage. While Sean speaks no German, his skills mean he will have little trouble finding a decent job.

“The referendum result has been a massive, massive blow. Both Sean and I are heartbroken. We’ve lost some very good friends over this. It was not an easy choice, but we don’t see a future in the UK any more – the country he was born and I chose to make my home and was very happy in.”

Since Melissa does most of her work for German clients, the UK won’t particularly miss her talents, although Sean will be harder to replace. Mathieu and Pauline, too, foresee big problems for their employers. There are only two or three people in the country with Pauline’s particular expertise, and it would take 18 months to train a replacement. When Mathieu’s boss was headhunted by Apple over a year ago, he had to deputise – and he’s still deputising, because they haven’t been able to replace him. And that’s with easy access to all 28 EU nations. The prospects for the company are not bright; only a handful of the staff in his team are British – there’s little appetite for computer science degrees in this country – and several other EU nationals are considering a fresh start.

***

Lara is another one whose skills will be sorely missed; she’s a GP. According to an estimate made last summer, EU immigrants make up 10% of registered doctors and 4% of registered nurses, making the UK health service one of the world’s most dependent on foreign labour. And with the GP system already being described as “on the verge of collapse”, that’s a talent pool the UK can ill afford to lose access to.

Lara, in her early forties and of mixed French and Mediterranean heritage, will also be taking a British partner with her when she goes, and two children. Again, she says, it wasn’t the Brexit vote per se that forced their hand. “Initially, after the vote, I thought, ‘It’ll be all right, they’ll guarantee our rights,’ but they never did.”

She too lays much of the blame at the door of the immigrant-bashing tabloid press. “Basically, all these endless stories about EU citizens stealing jobs and being scroungers made me feel not at home. I was in shock. Surely this is not the country I’d spent the last 22 years in? It suddenly felt foreign to me.”

While she hasn’t personally received any abuse – her English is flawless, her dress and appearance unexotic – she has witnessed some unpleasantness. “One of our patients – ex-army, I think – started shouting at some of the other patients, Polish and Asians, in the waiting room. ‘Britain’s for white people, get out of my country …’ I don’t think anyone would have said any of these things before the referendum.”

So next year, instead of taking home £48,000 as a doctor in the UK, she’ll be earning a little less to treat French patients instead. It’s her friends and colleagues, she says, that she’ll miss most. “I have amazing work colleagues. Even though some of them voted leave because they felt the EU had an unfair advantage over Commonwealth people.”

***

Linda, too, will be taking a native Brit with her when she leaves. Aged 37 and originally from Turku in Finland, she arrived here in 2003. “I had basically loved Britain since I first came here aged 16 and spent a month in Devon on a language course. I travelled all around Europe Interrailing, but nowhere else felt so ‘homey’.”

She runs a small market research company with a British business partner, for which she claims a salary of £70,000. “We started the company five years ago, and have grown to a team of 10, mostly Brits.”

As with everyone I interviewed, Linda considered applying for permanent residency, but found the process too daunting. “I reluctantly considered applying for PR about four months after the referendum. Having looked at my 14 years in the UK, no five-year period was simple or straightforward enough to not worry that it wouldn’t pass the hostile approach of the Home Office. For example, I’ve studied twice while I’ve been here, although working part-time both times, and I’ve been ‘unemployed’ (while building the company and living off my savings).”

Crunch time for Linda and Ian was the Conservative party conference in October 2016, when Theresa May first signalled her willingness to lead the UK to a hard Brexit. “We’d toyed with the idea of leaving from the morning of the referendum, but I’ve spent almost my entire adult life here, and leaving at 37 didn’t really appeal. But it became apparent to us that under Theresa May, the environment would become hostile for EU citizens, and we realised there was really no future here for us if Britain left the single market.” Ian works in the tech industry, which, they fear, will fade to nothing in a UK cast adrift from the bloc.

The lack of support from the government, and the failure of the Lords’ amendment to article 50 on EU citizens’ rights, came as a further blow. “The uncertainty was taking an enormous emotional toll on me, especially as I was recovering from the burnout I got from the early years of building the business. The anxiety was pushing me back to depression and Ian felt it was important to get me out of the UK for my emotional well-being.”

Linda is in no doubt that Britain has become a less tolerant and hospitable place since the vote. “I would go as far as to say it’s hostile,” she says. “I came to the UK partly because I felt it was more open-minded and tolerant than the country I grew up in – needless to say, that illusion has now been totally shattered.”

Are there any circumstances under which they would cancel their plans, or consider coming back? A soft Brexit, maybe? “Nothing. I can never feel at home in England or Wales again. But if Scotland becomes independent, we will strongly consider moving there, as that was our original plan.”

So as soon as they can make the arrangements, they’re relocating to the Netherlands. They’re sad to be leaving their friends, but she also has more mundane concerns: “I will miss having Amazon Prime, and going to Boots!”

One of Pauline’s greatest fears is losing access to Marmite – “God, I love Marmite!” – but mostly, she says, they’ll miss the Brits. Well, some of them.

“In the UK you find the very worst of people,” chips in an impassioned Mathieu. “Uneducated, almost as bad as Americans. But you also have the best people – oh, my God, wonderful people – who are so logical, considerate, articulate … They know how to talk. They are perfect.”

The trouble, apparently, is that there just aren’t enough of them. “I still have emotional attachment to the people – but people are not a place,” says Pauline with a sigh. “Home is literally where the heart is, and our heart is not in Britain any more.”

The Tories, Labour and the Liberal Democrats have all promised, as part of their manifestos, to make the rights of EU citizens in the UK one of their top priorities after the election. Alas, it looks increasingly as though that might be a case of shutting the strong stable door after the horse has bolted.

• Names have been changed.