“Will it come like a change in the weather?

Will its greeting be courteous or rough?

Will it alter my life altogether?

O tell me the truth about love.”

WH Auden

“So, Andy,” said Dad with a twinkle. “How do you fancy staying up late tonight?”

I was 11 years old. Bedtime on school nights was 8pm, 10 at the latest at weekends. To be allowed to stay up after Mum went to bed was a treat on a par with a personal visit from Tom Baker.

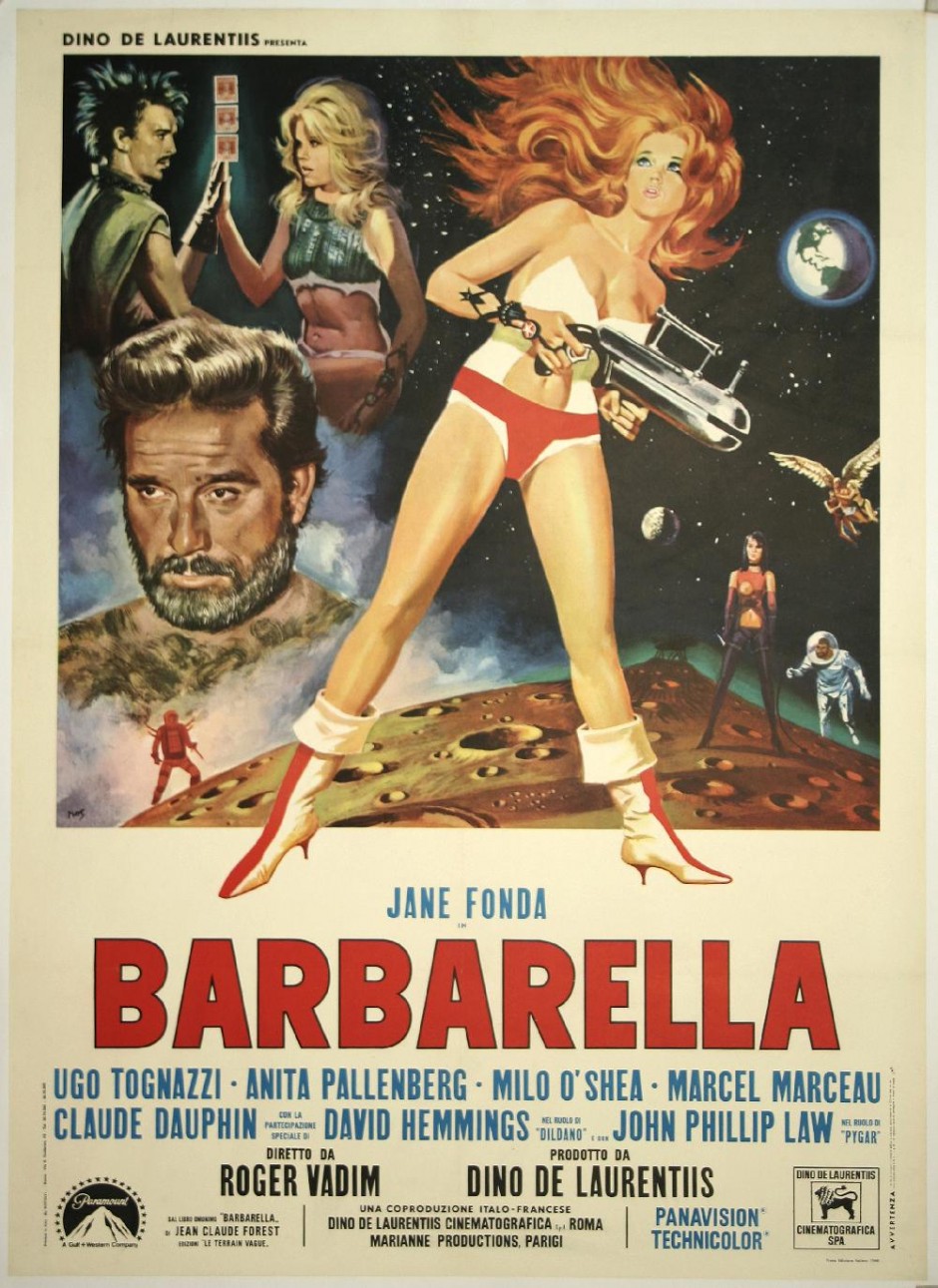

The reason for this break with protocol, it emerged, was that Dad wanted me to watch a film with him: Barbarella, the 1968 comic-book adaptation starring Jane Fonda as an interstellar explorer with an uncanny knack of losing her clothes. I enjoyed the film more for the robots and monsters than for Jane’s wardrobe malfunctions, although the semi-nudity did coincide with some stirrings which, at the time, I put down to Mum’s shepherd’s pie.

It was years before I worked out what was going on that night. Roger Vadim’s kitsch sci-fi romp was, I realised, the sum total of my parents’ efforts to explain to me the myriad complexities of human reproduction. No awkward birds-and-bees talk, no 1950s government information booklet “accidentally” left by my bedside; just a scantily clad spacewoman being pecked to death by budgerigars.

The state didn’t do much better. We had one sex education lesson, at the end of my second year, which consisted of two indecipherable diagrams, some vague mumblings about Aids, and a five-minute a video of a gruff-looking German woman unrolling a balloon over a stick. It was like teaching Mandarin from a takeaway menu. There was nothing about feelings; no clue as to whether this was roughly average size for a stick; and most importantly, no pointers on how to persuade the German woman to touch your stick in the first place.

The internet and self-help literature were years away. If I’d had any brothers or sisters, I might have gleaned the odd snippet by putting my ear to their bedroom door; as it was, the only scraps of information available were the eye-boggling fisherman’s yarns of the playground and the odd scrunched-up jazz mag abandoned in the woods. And with coordinated teams of torch-wielding teenagers combing for them in overlapping eight-hour shifts, those were hard to come by.

But I wasn’t too worried. Everyone else seemed to get by without an instruction manual. Sex obviously comes naturally to humans, as it does to the animals. I would instinctively know the right thing to do when the time came. Wouldn’t I?

♥ As you read this, a million people are having sex. (The World Health Organisation estimates that 100 million sex acts take place every day, and the average duration of intercourse is 7 minutes, which means that at any one moment, there are about 500,000 couples making whoopee.)

And when we’re not doing it, it’s never far from our minds. The oft-touted statistic that men think about sex every nine seconds is a myth, but various studies put the figure at anything between several times a day and once a minute. It’s reckoned that there are about half a billion pages of porn on the internet, and sexual images are everywhere, in newspapers and magazines, on TV and advertising billboards.

Yet for a species seemingly so obsessed with sex, mankind has been remarkably slow to learn about it. The derisory state of sex education in the 1980s isn’t actually that surprising when you consider that sex and love and relationships, were, until roughly that time, a mystery to everyone. Whether it was because sex was taboo, or because we felt the subject somehow beneath our attention – everyone knows how to have sex, don’t they? – there was practically no research into the field until the alarmingly recent past. John Farley, in his 1982 book Gametes and Spores, wrote: “Sex remains almost as complete an enigma today as it was 300 years ago when Dutch microscopists discovered minute ‘animalcules’ swimming about in human seminal fluid.”

Sure, we’d figured out the nuts and bolts – but even they were a long time coming. Sperm (as opposed to semen) were only discovered in 1677, and it was another 150 years before anyone clapped eyes on a human egg. Until the mid-18th century, most scientists still clung to the ancient Greeks’ theory that male semen contained complete human beings, and women were just a sort of incubator. (Oscar Hertwig finally vindicated women in 1875 when his experiments with sea urchins proved that both sperm and egg contributed genetic material to the embryo.)

Things didn’t move much quicker in the early 20th century. In 1933, Sigmund Freud advised those who wished to learn about women to “turn to poets, or wait until science can give you deeper and more coherent information”. Alfred Kinsey published his reports on human sexual behaviour in 1948 and 1953, and while they revealed a lot about what people did, they offered no explanation of why they did it. In fact, we’d split the atom, invented the laser and landed on the moon before anyone had even begun to address many of the fundamental questions of sex.

Why do we have sex? Why does attraction fade? Why do people cheat? Why are there so many female prostitutes, and so few heterosexual male ones? Why is it always men who propose? Why are so many women attracted to men who treat them badly? Why do you often see beautiful women with ordinary-looking men, but never the opposite? What is beauty anyway? Why is it more acceptable for men to sleep around than women? Why is it easier to meet a partner when you already have one? Why are there so many single mums and so few single dads? What’s so attractive about a sense of humour? And what, exactly, is chemistry?

Many of these questions hadn’t even been asked by the time I was born, and none of those that had had received satisfactory answers. The first breakthroughs to cast light on these issues came in the 1970s – although they were building on a theory that was more than 100 years old.