Can you love someone you’ve never met? Search engine says no:

A trawl of the net suggests this is the majority view. Human beings, after all, engage with the world and each other via their senses: sight, sound, touch, taste, smell (and at least four others, according to my QI Book of General Ignorance). All entail close proximity.

Besides, the internet is groaning with stories of how “I fell in love online but then we met in real life and he turned out to be 90/a ring-tailed lemur/a twat”. Love can only be real if you can be certain that the person is real, right?

Why, then, do literature and film offer so many tales of incorporeal love? Les Liaisons Dangereuses is a series of seductions by letter; ditto Rousseau’s La Nouvelle Héloïse. In Cyrano de Bergerac, Roxane is won over by the words of Cyrano (delivered by the oafish mouth of Christian). In Miklós László’s 1937 play Illatszertár – better known to most in the form of the 1940 Sullavan/Stewart romcom The Shop Around The Corner and the DEAR GOD WHY 1998 Hanks/Ryan remake, You’ve Got Mail – George and Amalia, two feuding employees in a Budapest gift shop, are each engaged in a romantic correspondence with a stranger. The twist, of course, is that they’re pen-fucking each other.

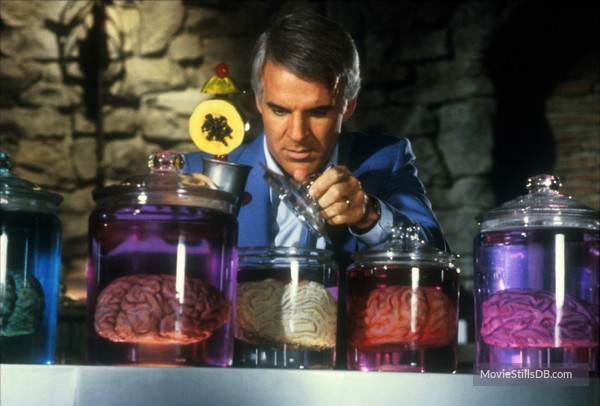

Steve Martin lusts after a cerebellum in a jar in The Man With Two Brains. Joaquin Phoenix goes all googly for a virtual assistant in Her (which I don’t quite buy, because while the idea of a woman who obeys your every whim and never complains is vaguely appealing, the idea of a partner who knows everything is not). And Beauty and the Beast and the Frog Prince are just two of countless fairy tales dealing with people falling for the intangible essence of a person rather than their physical self.

These are all fictions, but they are fictions that resonate, because we like to think that, deep down, we’re not shallow, and that we can love a person for their soul rather than their superficial, transient features.

In any case, it’s not as if remote romancin’ is a new phenomenon in the real world. Thanks to the social taboos around spending time alone with unmarried members of the opposite sex, love letters formed the greater part of the courtship process for centuries. Mozart and Constanza Weber, John Keats and Fanny Brawne, and Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning are just three of the more famous examples of loves forged or fortified in ink.

And because many countries (including the “civilised” western ones) have a long tradition of arranging marriages*, it’s long been common for people to have little direct contact before committing to each other. Here again, correspondence is encouraged: soul 2 soul > hole 2 hole. What’s more, it seems to work: the reported happiness within, and survival rate of, arranged marriages is considerably higher than that in modern “voluntary” ones.

(*As distinct from forcing them, of course.)

People have been holding torches for faraway souls – royalty, soldiers, actors, writers, Tannoy announcers – for as long as they’ve had imaginations, and the absent can get to you just as effectively as the present. This poor woman was so deeply affected by someone she met online that she ended up being prescribed the anti-anxiety drug Ativan.

***

The secret to this spooky action at a distance, of course, is humanity’s tour de force: language. With words, you can create a representation of yourself that is not confined to one point in space or time.

Some scoff at the idea that Russian- or Robert Mercer-sponsored Twitterbots and targeted Facebook ads might have influenced the EU referendum result and Donald Trump’s victory. To them, I mention only that half the human race still allow their every waking moment to be governed by diktats set down in books written 2,000 and 1,400 years ago.

Words are the clothes we wear in unreality. You don’t (often) get to make them, but you get to choose them, and how to combine them, and the “richer” you are, the wider the options open to you. With time, a spellcheck, maybe even a friend’s judicious eye, you can step out into the virtual world as if fresh from a Gok Wan makeover.

As the very existence of the field of forensic linguistics proves, your use of language is as unique to you as your fingerprint (assuming you’re not a copy-and-pasting Brexit fanatic). Your language reveals everything important about you: your values, your interests, your sense of humour, your level of education, and usually, despite your best efforts at airbrushing, your attitude to the world.

And it was precisely the discovery that others shared my values and humour that, over the last few months, brought together one of the most cherished groups of people I’ve been part of.

For me, it’s been the sole silver lining to Brexit. After bonding on Twitter over the inanities of the far right, a few of us started a chat with a view to meeting up at the March for Europe in London in March 2017. Only a handful made it, and we didn’t actually hang out for that long, but the chat chuntered on, and slowly, as we found more like-minded souls, we added them. Boys and girls, straight and bi, from Manchester to South Africa to Moscow, liberal and anti-fascist, mostly of a similar age (with me as extreme outlier).

There have been six or seven meet-ups now. Drinks on general election night were followed by an Ethiopian meal, then a canalboat cruise, then an eggs benedict sleepover. Geographical distribution means I haven’t met them all yet, but I’ve checked off about half the group in six months.

But like I said, screw the real-world stuff. Mostly we talk shit. We share pictures and jokes and tweets that we love, as most groups do, but we also flirt, sympathise, praise, share intelligence on Nazis, and sometimes get wasted and stay up all night playing Twitter Countdown. Oh, and because we’re all snowflakes that melt at any temperature above -272C, the slightest ill-considered comment can send any of us hurtling out of the group, only to return after three days or so of grovelling and cajoling.

In what’s been an exceptionally difficult year for me, thanks to some serious health problems, the Tits have been an endless source of support, fascination and joy (and grief, but nothing comes without a price). Less spooky action at a distance, more strong nuclear force.

***

The argument that virtual interactions are plainly inferior to real weakens with every passing day. The ability to share pictures, audio and video has already narrowed the perceptual distance between us, and as the functionality of social media is slowly engineered to replicate real-world interaction (Facebook and Twitter likes are nods and smiles; retweets and shares are laughs; gifs, I guess, are goofy facial expressions), so our online and real-world experiences fall into ever closer step.

You can’t entirely trust those visual and auditory signals, of course – catfishing is a real problem – and you still don’t get any hormonal chemistry online, one of the principal components of attraction.

Well, not directly. Recent studies have shown that getting likes and retweets from an online crush can cause a similar spike in the “love hormone” to that caused by physical contact. How fucked up is that? A little character appears on your phone, as a result of someone you’ve never met typing something into their phone a thousand miles away, and causes an actual chemical change in your brain! People can change your mood, and your mind, and your heart, from afar.

Then of course there are the aspects of remote relationships that are superior to their physical equivalents. Objectivity. Disinhibition. Novelty. The thrill of the not-quite-known.

In fact, if I ruled the world, I might insist that all future human relationships be conducted on a virtual basis. Because based on my record, I’m better off keeping the flesh well out of it. I might have a shot at charming your pants off from 500 paces, but move me 499 paces closer and chances are I’ll just soil my own.

People are, after all, just an idea, even when they’re in your arms. Sure, your proximate senses give you a firmer grip on that idea, but ultimately, you have no way of knowing for sure whether they are real, whether the sensations in your fingertips haven’t just been planted there by some malign entity. You might be living in the Matrix.

Meanings change fast. We use the word “virtual” these days in opposition to the word “real”, forgetting that until very recently its only sense was “almost or nearly as described”, ie pretty much as good as the real thing. I’d argue that before long, its semantics might morph again, so that it comes to mean “better than the real thing”.

“Hold up, Bodle!” you cry, smirking. “This is all very well, but you’ve missed out one crucial element. If you never meet someone, you can’t have sex with them.”

Ha, yeah! I used to think that too.